Nieman Journalism Lab |

| Monday Q&A: Evan Ratliff of The Atavist on the shift to device-agnostic reading Posted: 10 Sep 2012 09:45 AM PDT

When I spoke last week with CEO and cofounder Evan Ratliff, he said their next step is expanding their audience, both readers and authors publishing on the platform. A version of the core Atavist software — which lets authors create ebook-esque multimedia stories for devices like iPhones and Kindles — will soon be offered for free alongside the licensed version. With an increasing number of devices available to read books or longform journalism, Ratliff said the most important thing The Atavist can do is give people options to read however they like. Justin Ellis: You guys got some funding this summer. Tell me a little bit about what your plans are and what this big pile of money you guys got is going to help you do. Evan Ratliff: It’s a few things. I think the main impetus for wanting to raise the money, and also where we’re spending it in the short term, is just on our technology and our development. Which is both for the purposes of the platform that we have — and we’re launching that in a broader way — but also for our own stories and own publishing. We got to the point where we were pretty strained with all the things we were trying to do. And we didn’t want to stop experimenting with our stories. Essentially, we’re doing a lot of things at the same time, and we were coming up to a point where maybe people were working too hard — harder than they should. It’s about bringing in enough people that we can feel like every part of the business is moving forward at the same time. Ellis: I saw that you guys recently hired an editor. What’s he gonna do? Ratliff: So having Charlie [Charles Homans] — I don’t know if he goes by Charlie in a work context, but I call him Charlie — partly is just going to really help us get on a regular schedule when it comes to publishing. One of the things I think has been difficult for us is that we’re small, but we’re doing stories that are really ambitious. They have a lot of moving parts. I think we’ve been successful in getting those out, and I hope we’ve been successful in keeping the quality level up. But it always feels like a sprint. Hiring Charles is really about getting organized in a way that we can feel like: “All right, we know what’s in the pipeline, we know what’s coming, we can get the stories on time.” And it leaves space for me, for him, and for our tech team and everyone to be a little more more thoughtful about what it is we’re doing and where do we want to take it — as opposed to always saying, “Okay, all we have to focus on is getting something out.” Ellis: What do you think is next in terms of digital publishing? Obviously, you guys wanted to be ambitious and include more dynamic things inside ebooks. But what do you think is next? Ratliff: I think for us — I could never speak for the industry at large, because at some level I always feel I don’t know what I’m talking about, in terms of what other people or doing or what’s going to happen — I can say for us the next thing is definitely the ways in which we reach readers. That’s the most important thing that we’re focused on on the publishing side.

So, that means, as of our next story, which comes out a week, week and a half, we’ll be selling it directly on the web. So, rather than just selling through devices we’ll be selling it on the web and you can read it on devices. We really want to move to a setup where you’re buying the story from us and you’re able to read it wherever you want. So it’s really not driven by whether you have an iPhone or anything else — it’s actually driven by whether you want to read this story and then you can sort of pick your venue. We’re kind of moving things in that direction. Another aspect of that is figuring out subscriptions. So we’re gonna start experimenting with some different subscription types — probably we’ll start with something very simple in a few weeks, where it will be just for the iPad and the iPhone. But you’ll be able to subscribe to the stories we have coming for the next few months, get some access to the back catalog of stories we’ve already produced, and have that way of getting readers in. Ellis: Why subscriptions? Ratliff: Well, subscriptions might not be the right word. The word sort of carries some connotations that eventually may not fit. You could call it a membership, or you could call it some sort of book club. Offering people, people who like what we do in a more general sense besides just hearing about one particular story and saying, “Oh, I really want to read that ‘D for Deception,’” or “I really want to read that ‘Baghdad Country Club‘” — people who want more than one, we have technological ways to give them access to more than one at reduced prices. So it’s not strictly pulling a magazine model, but trying to say there’s multiple ways to get at what we do and if you really like it you’re better off buying this. Ellis: How important is that flexibility in purchasing and in platforms for readers? Ratliff: I think it’s crucially important. If I have one opinion about the book industry in general, it’s that, in terms of ebooks, which is basically what we’re doing, increasingly people don’t really care about the format. If you’re talking about a digital book, if they decide they want it, they want to read it on whatever their favorite thing is to read. I happen to really like reading on my phone and I read on my phone all the time. I buy Kindle books and I’ll read them on my phone. Obviously our app is on my phone. But people love the Kindle. People love their old Kindles. You have to get to a situation where you don’t care where people read it. If people want to buy direct from Kindle Singles, that’s fantastic for us — we love that, we’re a huge fan of that store. If they want to buy it from us and sideload it onto their Kobo, that’s also fine with us. Really, where it ends up makes no difference to us. What we really want to do is reach as many people as possible. And I think increasingly people do have opinions about where they want to access things. So we want to be available wherever they happen to access it. Ellis: The variety of devices available for this sort of reading seems to keep growing. Ratliff: Yeah, it seems like it. I can never keep up with the sort of latest “X million people own a tablet” kind of things. I should probably have those things at my fingertips, but I just sort of glance at those numbers and say “Wow, that sounds like a lot of people!” Certainly, unless the same people are buying all these tablets over and over again, it seems like it’s increasingly a place where people go. They get cheaper, and Amazon’s got new models in different sizes. You can basically find whatever it is you want — the one that goes in your pocket or the one that’s bigger, that’s a real tablet. I think to the extent they’re responding to what clearly seems to be a demand for this, there are only going to be more people reading on these devices. Now, that said, part of the reason we want to provide web access is we do want to make sure we can reach people might not have those. Ellis: You’re a writer who’s spent a lot of time the past couple of years delving into the business and technology aspects of publishing. What have you learned working on the other side? Ratliff: It’s been a very painful experience. I mean, painful in the sense that there are people who know everything you need to know about starting and running a business, and I was not one of those people. Fortunately, I have some tech background, so I’m a little bit fluent on that end of things. On the business end of things, much less so. I think the thing that surprised me most — which, looking back I shouldn’t have been surprised about — was that there are a lot of extraneous things involved in business that have nothing to do with doing the thing you actually set out to do. Like raising money.

We’re really excited about the investors we have, and we’re happy to have gone through that process, although we’re still kind of closing it out right now. It took a tremendous amount of time. At some level, raising money — obviously it’s connected to what we want to do, but it’s not doing what we want to do. So it’s not something that’s easy to celebrate. We can really celebrate when we put out a story, or we have someone new to the platform and they launch their app, or we’re getting people into the beta and they’re creating something really interesting. But “Hey, we went out and raised a lot of money” — it doesn’t feel like we did anything, because we didn’t do anything. We got the resources to do something. Ellis: Do you think that being an outsider to that end of things was helpful in some way? It would obviously be different if you guys were MBA-types and had everything put together from the get-go. Ratliff: I think it would be different. I think we did have advantages. We were at some level people who made things like stories — or in Jefferson’s case making websites and apps — so we kind of understood what it took to create those things. If you look at the software, it’s really built around the needs that we had and continue to have. And now we have other clients and people who use it who we can ask what they need as well. But really, I think that was an advantage: We were building something for us. We weren’t building something saying, “I bet there’s a market out there for this, so if we make it, people will come use it.” It’s actually intended to create. The other advantage is we were both freelancers — Jefferson and I were freelancers, and we were used to running everything on a shoestring and working odd hours. Ellis: What’s that like, to create something that has the potential to help other writers make a living or supplement their living? Ratliff: That’s certainly the most fulfilling part of the whole thing for me. Even on our publishing side, there’s no better moment in our process than when I write a check for a writer. That’s what we originally set out to do — for people to get paid to do the things I really like to read. And now we’re sort of figuring out how to use the platform to do that on a slightly broader level. If we can achieve that, it feels like there’s a lot of pressure around that. If you say “We’re gonna try to help people make a living,” then you’re on the hook for actually doing that. But we’ve seen some really encouraging things. It’s not necessarily as direct as they’ll sell their stuff and make a living. Ellis: Someone is writing through The Atavist isn’t going to become a millionaire, but she’ll probably make some money. And the types of stuff you guys produce is long, but not quite the length of a book. So it seems like you guys are fitting into wedges. Does that make sense? Ratliff: Yeah, I hope so. I think it’s always been a challenge — even in the sort of heyday of magazine writing, if there was such a thing — it’s always been a challenge to making a living doing that kind of work as your job. So I don’t think being that wedge is necessarily going to solve that problem. But I do think there is a space in there — and now it’s more than us in there — that didn’t really make sense in the pre-digital world. And now it does make a lot of sense. And now there’s a way to make at least — it’s still a little hit-driven — make enough money to say people can keep doing this. That’s where we are now. The question is can we move it further from there? Ellis: Who would you really like to see writing on The Atavist platform? Ratliff: What I’d really like to see, and I don’t mean to call him out by name and say he should do it, but you look at someone like Robin Sloan, who is just incredibly creative — he clearly has ideas for all sorts of projects and he goes and executes those projects. Whether it’s raising money for a novel on Kickstarter, or doing an app. I don’t mean him specifically, although that would be great — I mean people that have these sort of creative ideas that don’t necessarily fit in somewhere. Conversation lightly edited and condensed. |

| Eric Newton: Journalism schools aren’t changing quickly enough Posted: 10 Sep 2012 07:40 AM PDT

Editor’s Note: It’s the start of the school year, which means students are returning to journalism programs around the country. As the media industry continues to evolve, how well is new talent being trained, and how well are schools preparing them for the real world? We asked an array of people — hiring editors, recent graduates, professors, technologists, deans — to evaluate the job j-schools are doing and to offer ideas for how they might improve. Over the coming days, we’ll be sharing their thoughts with you. Here Eric Newton, senior adviser to the president at Knight Foundation, argues that journalism schools need to develop a culture of rapid change to keep up with the world around them. Representatives from six foundations this summer wrote to the presidents at nearly 500 colleges in the United States, saying their journalism and mass communication education would get better if it could change faster. Together, we have invested hundreds of millions in programs at hundreds of campuses. We knew the digital age had turned our field upside down and inside out. But it had not done the same to journalism and communication education. Schools that won’t change risk becoming irrelevant to private funders — and, more importantly, to the more than 200,000 students and the 300 million Americans they seek to serve. Without better-equipped graduates, how can we be sure future generations will have the news and information they need to run their communities and their lives? We noted the digital age has disrupted traditional media economics, and that in America today there is a local journalism shortage. Thus, the “teaching hospital” model of journalism education — learning by doing in a teaching newsroom — seems promising. Students use digital media to inform and, hopefully, engage a community. This digital model requires top professionals in important positions in academia, treated equally with top scholars. Having more top professionals around would, for most schools, be a big change. The funders didn’t think our letter was all that controversial. What’s the counterargument: that communication schools should ignore professionals, change slower, and get worse? Yet both the Chronicle of Higher Education and Inside Higher Education covered the letter. The journalism educators’ convention and the listservs buzzed. “Change? They don’t understand!”Some educators said there was no need to talk of change: They’d already done it. Those folks missed the point. We’ve entered an era of continuous change. Did you change last year? You’re a year behind. Did you go digital in 2002? You’re a decade behind. The “we have changed” group includes those saying “our PhDs started out as professionals,” not realizing that folks from last century’s non-digital newsrooms are not the digital pros we’re talking about. Others opined that we cared only about gizmos, not content. Yet smartphones are not a fad. Nor is social media or the World Wide Web. They are no more “gizmo” than the printing press was. They are driving a global revolution in digital content. For the first time in human history, billions of people are walking around with digital media devices linked into a common network. A few professors claimed it was “anti-intellectual” to call for useful research, even if it helps us understand the technique, technology, and principles at work in this new age. When we asked about the major breakthroughs their theoretical papers had produced, or even who funds them, they fell silent. Yet we desperately need a change here: We need better research that helps us understand the science of engagement and impact. Good things are happening

The digital age is changing almost everything — who a journalist is, what a story is, which media work to provide news when and where people want it, and how we engage with communities. The only thing that isn’t changing is why. We still care about good journalism (and communications) because in the digital age they still are essential elements of peaceful, productive, self-improving societies. The “creative destruction” of educationUniversities must be willing to destroy and recreate themselves to be part of the future of news. They should not leave that future to technologists alone. Journalism and communication schools must begin to change radically and constantly. Change to do what? To expand their role as community content providers; to innovate in digital technique and technology; to teach open, collaborative methods; and to connect to the whole university. The best schools realize that having top professionals on hand is as important as having top scholars. “Top” is the key word: Quality today does not mean a long career or a famous name. It means you are good at doing what you do in today’s environment. You don’t have to be a big school to make a difference. Look at Youngstown, Ohio, where students are providing community content as though they were attending Berkeley, USC, Missouri, or North Carolina. Want a simple guide to a journalism or communications school? Look at its website. WordPress templates look better than many of them. Why is it acceptable for millions of Americans to communicate digitally in better-looking, more professional ways than the experts at universities? There are hundreds of hard-working deans and directors, excellent applied researchers, brilliant professors, wonderful early adopters, growing numbers of digital innovators, and creative agents of change. To you, we say congratulations — you know how to change, so please, don’t stop. We need you to keep trying new story forms, teach data visualization, do computational journalism, develop entrepreneurial journalism, build new software, and even pioneer things like drone journalism. We need you to keep learning from the students, the first generation of digital natives, as fast as you teach them. “Each and every person in this room”No institution within journalism education has achieved all that can be achieved. There are some big missing pieces. Journalism and communication schools could, for example, be some of the biggest and most important hubs on campuses. They could be centers for teaching 21st century literacy — news and civics literacy along with digital media fluency — to the entire student body. They could, but with only one or two exceptions, they aren’t. Yet democracy today is only as good as its digital citizens. The News21 project at Arizona State shows us what’s possible in journalism education and why it’s important. This year’s investigation found only a tiny number of cases of voter fraud, raising questions about the legality of the organization that pushed for states to enact voter ID laws. Everyone from Jon Stewart to The Washington Post used the stories. This is student work and journalism education at its finest. It makes me optimistic, as Gingras was as he ended his talk at the journalism education convention in Chicago:

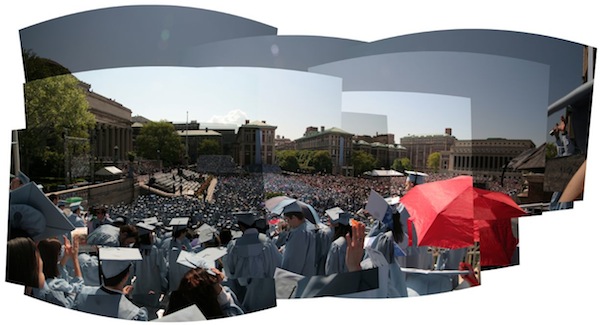

Panorama of Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism commencement by Lam Thuy Vo used under a Creative Commons license. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |