Nieman Journalism Lab |

- New Read It Later data: What does engagement look like in a time-shifted world?

- The newsonomics of Google’s retail push

- Tom Stites: Layoffs and cutbacks lead to a new world of news deserts

- A Y Combinator for public media: PRX, Knight launch a $2.5 million accelerator

- New York Times Election 2012 iPhone app launches

- Civic journalism 2.0: The Guardian and NYU launch a “citizens agenda” for 2012

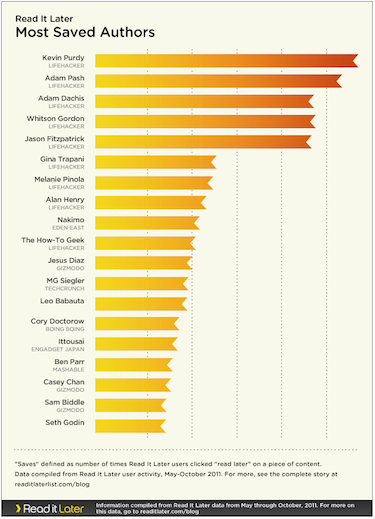

Posted: 08 Dec 2011 11:45 AM PST  This morning, Coco Krumme and Mark Armstrong — newly of Read It Later and always of @Longreads — released a study of Read It Later data examining stories that were saved by Read It Later’s 4 million-and-counting users over a six-month period (from May 1 to October 31, 2011). Together, David Carr put it, the data are part of a broader group of statistics that are emerging in the digital space to lend insight into “what kind of writing and writers are the stickiest.” (More bluntly: “What Writers are Worth Saving?“) This morning, Coco Krumme and Mark Armstrong — newly of Read It Later and always of @Longreads — released a study of Read It Later data examining stories that were saved by Read It Later’s 4 million-and-counting users over a six-month period (from May 1 to October 31, 2011). Together, David Carr put it, the data are part of a broader group of statistics that are emerging in the digital space to lend insight into “what kind of writing and writers are the stickiest.” (More bluntly: “What Writers are Worth Saving?“) While the findings about overall article saves are pretty fascinating — go, Denton and Co.! — what I’m most interested in are the sample’s return rates, the stats that measure actual engagement rather than one-off story saves. Because, if my own use of Read It Later and Instapaper are any indication, a click on a Read Later button is, more than anything, an act of desperate, blind hope. Why, yes, Foreign Policy, I would love to learn about the evolution of humanitarian intervention! And, certainly, Center for Public Integrity, I’d be really excited to read about the judge who’s been a thorn in the side of Wall Street’s top regulator! I am totally interested, and sincerely fascinated, and brimming with curiosity! But I am less brimming with time. So, for me, rather than acting like a bookmark for later-on leafing — a straight-up, time-shifted reading experience — a click on a Read Later button is actually, often, a kind of anti-engagement. It provides just enough of a rush of endorphins to give me a little jolt of accomplishment, sans the need for the accomplishment itself. But, then, that click will also, very likely, be the last interaction I will have with these worthy stories of NGOs and jurisprudence. (“Saving…saved!…gone!”)  It’s when I’m actually looking at my Instapaper or Read It Later queue that things get real. That’s when the Aspirational Read and the Actual Read duke it out for my attention. Do I really want to read about how GOP senators’ positions on Consumer Financial Protection Bureau are aligned with that of the industry? Or would I — alone with my thoughts and my iPhone — really kind of prefer to read something from The Awl? It’s when I’m actually looking at my Instapaper or Read It Later queue that things get real. That’s when the Aspirational Read and the Actual Read duke it out for my attention. Do I really want to read about how GOP senators’ positions on Consumer Financial Protection Bureau are aligned with that of the industry? Or would I — alone with my thoughts and my iPhone — really kind of prefer to read something from The Awl? This is what makes the Read It Later dataset so interesting. The line between the aspirational and the actual is thick: There’s precious little overlap between the most-saved authors and the authors with the highest return rates. “Engagement” isn’t really “engagement”; it’s not a static thing. What we think we want in a given moment — life-improvement advice, tech news — may well be quite different from what we want once we’re removed from that moment. (Which is to say: Interest, like everything else, is subject to time.) What does endure, though, the Read It Later info suggests, is the human connection at the heart of the best journalism. While so much of the most-saved stuff has a unifying theme — life-improvement and gadgets, with Boing Boing’s delights thrown in for good measure — it’s telling, I think, that the returned-to content can’t be so easily categorized. It runs the gamut, from sports to tech, from pop culture to entertainment. What it does have in common, though, is good writing. I don’t read all the folks on the list, but I read a lot of them — and I suspect that the writing itself, almost independent of topic, is what keeps people coming back to them. When I’m looking at my queue and see Maureen O’Connor’s byline, I’ll probably click — not necessarily because I care about the topic of her post, but because, through her snappy writing, she’ll make me care. The Read It Later data suggest a great thing for writers: Stickiness seems actually to be a function of quality. Or, as David Carr might put it: The ones worth saving are the ones being saved. |

Posted: 08 Dec 2011 09:00 AM PST  It looked like just more head-butting among the mammoths of our time: Google will match up with Amazon, said the Wall Street Journal last week: “The Web-search giant is in talks with major retailers and shippers about creating a service that would let consumers shop for goods online and receive their orders within a day for a low fee.” Most of the stories played on that Goliath vs. Goliath theme, and of course that’s an increasingly familiar one as the businesses of Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple overlap, intersect, and collide. Who is a bookseller? Well, Amazon, and Apple, and Google, kind of. Who is selling and renting media — well, who isn’t or preparing to do so? Who is in the hardware biz — all except Facebook? Who’s reaching for the digital ad riches, now generating $80 billion worldwide; Google, the king, and Facebook, the fast-threatening prince. Yes, the Google/Amazon match-up over delivering goods is a good and real storyline. As big brains butt, it could be thunderous and landscape-changing. That landscape includes the news business, and you can almost feel the rumbles underfoot just with the word of Google’s move. Let’s look at the newsonomics of Google’s would-be one-day-shipping program — let’s call it Google Tomorrow™© — and its wider impacts and strategic rationale. First, we’re talking about a lot of potential money. U.S. retail e-commerce is forecast to hit almost $200 billion this year, with the global total adding up to $700 billion. So there are many companies trying to get in the middle of it. The idea of website-facilitated buying — and shipping — from fairly local retailers isn’t a new one by a longshot. Storerunner plied this territory, too early, a decade ago. Webvan, the best funded of the grocery deliverers went from brilliance to punchline in about 30 seconds. Shoprunner is currently out there, pitching the same idea as Google Tomorrow. Newspaper companies have been more steadfast, more the tortoise in the race for perfection of our emerging online/offline commercial world. Companies like the Gannett-owned ShopLocal and independent Travidia, with its FindnSave product used by McClatchy and other news chains, have been building the know-the-local-retail-inventory, compare-prices-and-buy terrain for years. Unlike what Google may do, they don’t deliver one-click buying and delivery. They offer product selection, availability and then click off to retailer’s own sites for buying and shipping or store pickup. The idea seems like a great one, a merger of the best of online and offline, yet it’s been slow to grow. Every time I’ve checked out the sites, I’ve found the promise smart, but the inventories too uneven or the hierarchy of results skewed to preferred shops — not my preferences. Consumers have clearly opted for Amazon over these kinds of sites. The impact on the ShopLocals and FindnSaves is not what should concern newspapers, though. The big issue: retail advertising. While the web has greatly damaged newspapers’ classifieds and national ad businesses, retail has been a relatively stronger area. Worth about $13 billion last year — or half of daily newspapers’ ad revenue — it’s a lifeline at this point in the tough print-to-digital transition. Retail is being challenged on several fronts, with the Sunday preprint business a big concern. In fact, both Google and newspapers are pursuing e-circulars to counter the inevitable print downturn in that area. Wait a minute, you may say — that $13 billion is advertising money and Google, like Amazon, wants to make money facilitating actual commerce. But the division between advertising and selling is an old one, fast blurring. Think about where we’ve come from the era of impression-based (newspaper, TV, radio, magazine) ads into the era of pay-per-click, pay-per-lead, pay-per-acquisition, and more. Retailers don’t want to advertise; they want to sell stuff. Give them new routes to sell stuff, and deliver it more cheaply than they could before, and they’ll migrate their ad/marketing/lead generation dollars. So if Google can really make it easier to personalize, routinize and make more efficient the selling process, it will place itself between the seller and the buyer. As it does that, it replaces the newspaper as middleman, further reducing much of the revenue that is keeping newsrooms staffed, even if many of them are now half-staffed at best. Is the replacement of newspaper as advertising-oriented middleman inevitable? Probably, but over a longer term. Since the dawn of the web, people have been chasing the perfection of commerce, and it’s been a tough slog with far more losers than winners. Amazon, of course, is the big winner, but with relatively small profits, a paltry $63 million in the last quarter on sales of $10.8 billion. While Amazon is perfecting commerce, it’s got a long way ago. Since it was born in 1994, four years before Google, it has built a one-of-a-kind business on customer obsession and brilliant analytics. Its recommendations engine is ready for the web hall of fame, and its latest foray with Prime membership (“The newsonomics of Amazon’s prime moves“) shows it knows how to build on its foundation. Google lacks some of Amazon’s core strengths. It’s a mix-and-match technology company, famously trying lots of things and at times more quickly abandoning losers. In commerce, Google is moving forward with a spate of moves. Google OnePass is a restyled content buying system, with some prominent publishers signing on. Add in Google Latitude, Google Local, Google Local Shopping, Google Shopper, Google Tags, and Google Places, all relating to local commerce. Google Offers is gaining steam and is working with publishers on syndicating local daily deals. There’s an irony to such publisher partnerships, of course. On the one hand, Google is a “partner,” magnifying publisher businesses through its ad and search products. On the other, initiatives such as Google Tomorrow are a potential dagger to newspapers’ jugular. That’s the way of the web world. For Google, or Amazon, or Apple, or Facebook, any new initiative it takes on has its own internal logic. Should another industry — say newspapers — be wounded in the process, it’s just collateral damage. Given the size of these digital behemoths, as they decimate legacy industries, you can almost hear them say, “Sorry, did I sideswipe you? I didn’t feel anything.” If everyone is a frenemy these days, and Google is taking on Amazon, media companies have to ask: Who is the frenemy of my frenemy? One last point to ponder about Google Tomorrow. Consider it, in part, a defensive move. If, in fact, selling and advertising are blurring, Google has to move more in the selling direction. Right now, it’s an ad company, pure and simple. About 97 percent of its revenue comes from advertising (and you thought newspapers relied too much on that revenue source). It has brilliantly moved to expand its digital ad dominance (now taking in about 40 percent of the dollars in the U.S.) by merging its paid search foundation with big acquisitions in display advertising and mobile. Just last week, the feds let it buy AdMeld, an ad optimizer — and Google’s 57th acquisition so far this year. Now, the Doubleclick ad management system offers a singular approach, incorporating in one place display, search and mobile, to the delight — and terror — of publishers and others in and around the ad industry. The dominance is a sight to behold. Yet as digital innovation continues to disrupt everything in its path, the ad business is vulnerable, with companies, led by Amazon trying to eliminate the cost and friction of finding buyers. So let’s look at the Google Tomorrow battle plan as one aimed at Amazon surely, but with ammo that may hit newspapers as well — and one that may allow Google to find that big, elusive second revenue stream. Photo of Amazon warehouse by Chris Watt/Scottish Government used under a Creative Commons license.  Each week, Ken Doctor — author of Newsonomics and longtime watcher of the business side of digital news — writes about the economics of news for the Lab. Each week, Ken Doctor — author of Newsonomics and longtime watcher of the business side of digital news — writes about the economics of news for the Lab. |

Posted: 08 Dec 2011 08:00 AM PST  Editor’s note: Tom Stites had a long career in newspapers, editing Pulitzer-winning projects and working at top newspapers like The New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, and the Philadelphia Inquirer. In recent years, he’s shifted his emphasis to trying to figure out a new business model to support journalism through the Banyan Project. This week, Tom outlines his beliefs on where web journalism stands today and one model he thinks might work; here’s part one. Here’s a challenge: Name a straightforward two-word phrase related to journalism that you can enter in Google and get only one result.Stumped? Try “news desert” — one, and only one, direct hit.1 Now check Wikipedia. “News desert” comes up entirely empty — but “food desert” gets 3,400 words. Any why not? Hunger is a crucial issue, and “food desert” provides a vivid frame that elicits a mental movie of hungry people crawling over arid dunes in search of an oasis for sustenance. Frames matter. They determine how an issue is understood, driving this understanding into the language and thus into people’s thinking about what actions to take. One proof of the power of “food desert” as a frame is that a Google search yields thousands of direct hits — including links to serious actions people have taken, including the Agriculture Department’s food desert locator and to Food Desert Awareness Month. But isn’t it also a crucial issue that a huge part of the American people, the less-than-affluent majority, is civically malnourished due to the sad state of U.S. journalism — and that the nation’s broad electorate is thus all but certainly ill informed? It has long troubled me, and many others, that an issue so central to democracy has such a peripheral role in the discourse about journalism’s future, which tends to focus more on crowdsourcing, Twitter and Facebook, aggregation vs. original reporting, how AOL is faring with Patch, and search engine optimization. These are important topics, but perhaps an energizing frame like “news desert” can widen the aperture of thinking about journalism’s future and sharpen the focus on people’s and democracy’s needs — on journalism as public good. Elites and the affluent are awash in information designed to serve them, but everyday people, who often grapple with significantly different concerns, are hungry for credible information they need to make their best life and citizenship decisions. Sadly, in many communities there’s just no oasis, no sustenance to be found — communities where the “new news ecosystem” is not a cliché but a desert. The Chicago journalist Laura S. Washington introduced me to the desert frame, and she credits a South Side community organizer for originating it. Washington used it in her remarks in April when she and I were members of a panel called Journalism and Democracy: Rebuilding Media for our Communities at the 2011 National Conference for Media Reform. Suddenly a movie was running in the little screen in my mind: The protagonists were losing sleep on a hot night, worrying over life issues they might be able to resolve if only they had the right information — but there was no news oasis in the landscape of their lives, so they just kept tossing and turning. I couldn’t see if movies were playing in the heads of the hundreds of people in the hall listening to our panel, but they clearly got exactly what Washington meant. So I’ve been using “news desert” in conversations and presentations over the last six months. It never fails to communicate powerfully. “Gee,” a community leader in Haverhill, Massachusetts, said when I used it. “That sure describes us.” Haverhill is a middle-income city of 60,879 whose daily newspaper and community radio station folded years ago and whose sole weekly is withering — and it will be the pilot city for the Banyan Project, a web journalism startup I lead that’s designed to sustain itself while serving communities and publics that other media tend to ignore. News deserts are places whose economies cannot sustain any established business model for journalism, for-profit or nonprofit, and Haverhill exemplifies one kind: municipalities whose news institutions have failed or faded as advertising has dried up and can no longer come close to meeting the information needs of the community and its people. Many rural communities fit this category as well. Demographics rather than political boundaries define other news deserts categories. In a speech at the Media Giraffe Project’s 2006 Conference, I laid out how metropolitan newspapers across the land tailor their coverage to serve readers in the top two quintiles of the income distribution, ignoring the quite different information needs of everybody else — and that was before the five-year newspaper ad revenue nosedive caused widespread layoffs, further shriveling the supply of original reporting that is the bedrock of journalism’s public good. I didn’t have the news-desert frame back then, but when it comes to life-relevant original reporting it’s clear that it describes where the less-than-affluent American public tends to live. Minority communities in big cities tend to be the most arid news deserts of all, a point Washington made in her NCMR panel presentation and in an In These Times essay. (A Chicago blogger’s item calling attention to her essay is the source of that one and only Google hit.) Washington’s desert phrase was a bit different. “We live in a communications desert,” her essay begins. “How can this be, you say? Our 24/7 news cycle delivers…millions of words, bytes, video clips, posts, emails and tweets…Yet paradoxically, in this ‘revolutionary’ media age, our cities are parched for information and news coverage with context and quality.” She cited foundation-funded research aimed at assessing the news needs of low-income and minority communities on Chicago’s West and South Sides. Low-income respondents in an 800-person phone survey were less connected than others on every measure tested. People told focus groups that they read Chicago’s dailies but found little that resonates with their lives. And it’s not just the newspapers. In a speech in June, FCC commissioner Michael Copps cited a study that shows that black or Hispanic populations have fewer Internet-only news sites. “If the majority of hyperlocal sites are taking hold in affluent areas that can support advertising,” he said, “have we really dealt with diversity and competition, or have we just moved media injustice onto a new field?” Desertification is on the march, claiming more and more communities as newspapers continue to wither and few Web efforts manage to replace more than a fraction of the original reporting that newspapers have abandoned (see Part I of this series). There are fresh examples from week to week and from coast to coast, but none is more vivid, or sadder, than the dramatic increase in aridity that newspaper readers in San Francisco Bay communities are surely experiencing right now. The Bay Area News Group, which had been 13 dailies published by the Denver-based MediaNews chain, last month cut 34 newsroom positions across the group and combined five of its titles into two; in total, more than 100 employees lost their jobs. In one stroke, three papers died and the 10 survivors were all wounded. Readers will find the papers less reflective of their communities — they’ll have local news sections and most will have familiar nameplates, but their general news, sports, and comics pages will be more uniform. And, with the shrunken staff, original community reporting, which has been drying up for years as newspapers laid off reporters, will become even more parched. Eric Newton, now senior advisor to the president of the Knight Foundation, was managing editor of The Oakland Tribune 20 years ago. In a posting to the Knight Blog, he recalled that he’d supervised a staff of 130 full-time journalists; after years of attrition the newsroom was home to only a dozen reporters — and this was before the newest cutbacks. Newton recalled that Bob Maynard, The Tribune’s revered late publisher, had referred to the daily newspaper as “an instrument of community understanding.” Newton added, “We need some new instruments.” Tomorrow: Might the elusive Web journalism model be neither for-profit nor non-profit? Tom Stites, president and founder of the Banyan Project, which is building a model for web journalism as a reader-owned cooperative, was a 2010-2011 fellow at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard. Photo of Morocco’s Erg Chigaga by Joshua Benton.Notes

|

Posted: 08 Dec 2011 07:00 AM PST A new Public Media Accelerator, funded by $2.5 million from the Knight Foundation, will rapidly fund disruptive ideas in public media, PRX announced today.  The final details are still being worked out, but the accelerator is modeled on successful startup-focused initiatives like TechStars and Y Combinator. Technologists and digital storytellers will compete for cash to build their ideas. Winners will come to Cambridge for intensive, 12-week development cycles, under the guidance of mentors with deep experience in the field, all culminating in a demo day and the chance to win additional rounds of funding. The final details are still being worked out, but the accelerator is modeled on successful startup-focused initiatives like TechStars and Y Combinator. Technologists and digital storytellers will compete for cash to build their ideas. Winners will come to Cambridge for intensive, 12-week development cycles, under the guidance of mentors with deep experience in the field, all culminating in a demo day and the chance to win additional rounds of funding.“In the digital domain we’re not setting the pace for innovation in the same way we did in the broadcast world,” said Jake Shapiro, the executive director of PRX. The accelerator is welcoming both nonprofit and for-profit ventures, unusual for public media. Shapiro said he wants to attract top talent, people who might never consider the field otherwise. Last week, writing for Idea Lab, Shapiro said he observed a “worrisome gap” between coders and storytellers, estimating that fewer than 100 of the 15,000 people in public broadcasting are developers : As public broadcasting goes through its own turbulent transition to a new Internet and mobile world, the technology talent gap is a risk that looms large. Yes, there are many other challenges…But the twin coins of the new digital realm are code and design, and with a few notable exceptions, public media is seriously lacking in both.A shortage of innovation is not unique to public media, he told me. Nonprofits suffer constraints on financing ideas to scale, a lack of risk capital, and a lack of investment in deep R&D and technology, Shapiro said. The accelerator “gives license to risk in a more intentional way, and we definitely need more of that.” The Public Media Accelerator is also another sign the Knight Foundation is taking cues from Silicon Valley’s startup culture. Knight will retain a financial stake in for-profit ventures that receive seed money, moving away from its traditional role as pure philanthropist. Earlier this year, Knight launched a venture-capital enterprise fund. And in October, senior adviser Eric Newton said the annual Knight News Challenge, a five-year experiment, will speed up to three times per year, starting in 2012. “As we’ve started funding more smaller entities and startups, that model makes a lot more sense for us,” said Michael Maness, Knight’s vice president of journalism and media innovation. “That model allows us to go smaller, faster, more nimble.” Even the program came together fast: Shapiro approached Maness and Knight’s John Bracken with the idea in July. Board approval came in September, and the project will formally get underway at SXSW Interactive in March. So if for-profits are making public media and funders are buying stakes in startups, is it “public media” anymore? What is public media, anyway? “It’s about intent and values and goals and impact,” Shapiro said. “I’ve been in endless philosophical conversations about ‘what is public media’ over the years, and in some cases there are examples of pub media that are completely outside our field. I think on good days The Daily Show is public media…I think Wikipedia is public media. I’d rather just claim them than have to reinvent them,” he said, half-joking. The Public Media Accelerator immediately begins searching for a director to administer the fund and an advisory board. Shapiro, Manness, and Bracken will remain as advisers. |

Posted: 08 Dec 2011 06:00 AM PST  Big, rapid change can be hard to implement at any organization the size of The New York Times, so I appreciate how the talented journalists, designers, and coders within the Times use offshoot or ancillary projects to try out new features or ways of approaching the news. Its new Election 2012 iPhone app, which launched this morning, features some fresh design elements — most notably, story clusters that tie a Times story to a number of other stories around the web. Big, rapid change can be hard to implement at any organization the size of The New York Times, so I appreciate how the talented journalists, designers, and coders within the Times use offshoot or ancillary projects to try out new features or ways of approaching the news. Its new Election 2012 iPhone app, which launched this morning, features some fresh design elements — most notably, story clusters that tie a Times story to a number of other stories around the web. For example, the current top story is this one on Democrats seeing the GOP primary as a two-man race. That’s shown as the lead story in a cluster that also includes this Washington Post story, this Business Insider story, and this Washington Examiner story. (Some interesting choices there! I also see links to National Journal, the Los Angeles Times, Talking Points Memo, CNN, and a YouTube video.)  Maybe most interesting of all, one of the current top items in the app isn’t a New York Times story at all. It’s actually a one-sentence summary of a L.A. Times story on Sarah Palin (“Sarah Palin said she would not weigh in early on the G.O.P. race, but she did offer praise for Newt Gingrich and the Trump debate”), on top of a link to the LAT story making that exact point. Maybe most interesting of all, one of the current top items in the app isn’t a New York Times story at all. It’s actually a one-sentence summary of a L.A. Times story on Sarah Palin (“Sarah Palin said she would not weigh in early on the G.O.P. race, but she did offer praise for Newt Gingrich and the Trump debate”), on top of a link to the LAT story making that exact point.The glorified link is given the same weight in the app’s UI as a regular Times story. That feels noteworthy to me — I can’t think of anything else as linkbloggy that the Times has ever done. It’s telling this is happening on the national politics beat, which is both a space where the Times invests heavily in coverage and perhaps the space where the Times faces the most vigorous competition, online and off. A true political junkie probably checks in daily with the Times, the Post, Politico, TPM, the Daily Caller, National Journal, the LAT, particular bloggers — so the key to getting the target market to actually launch this app is probably to satisfy the needs of those wandering eyes. I assume, but don’t know, that these external links generated using tech from Blogrunner, the aggregator the Times Co. bought some time ago — although the promo site says “our editors” pick the stories, so maybe it’s a human-machine hybrid. (Update: The Times’ Fiona Spruill tells me it’s all human: “the links are hand-picked by an editor. Not using Blogrunner.”) The non-NYT articles open in a webview in the app. The Times has gone through a few iterations of how best to aggregate the rest of the web for its readers (you may remember Times Extra, the green external links on the front page that lasted only a year), but this one hits an interesting mix of Times dominance and reader service. Maybe more importantly, the app’s full content is only available to digital or print subscribers, which means it ties into the all-access model our own Ken Doctor talks about so much. For existing subscribers, this’ll serve as a nice surprise, a bonus to send home the value of a sub; for non-subscribers, it’s another little incentive, another reason to pony up. |

Posted: 08 Dec 2011 05:30 AM PST  Last August, Jay Rosen published a blog post arguing for “a citizens agenda in campaign coverage.” The idea, he wrote, “is to learn from voters what those voters want the campaign to be about, and what they need to hear from the candidates to make a smart decision.” And the method of doing that, he suggested, is simply to ask them: “What do you want the candidates to be discussing as they compete for votes in this year's election?” Today, that idea gets one step closer to reality. Rosen and Amanda Michel — currently The Guardian US‘s open editor and formerly Rosen’s colleague at HuffPo’s 2008 OffTheBus project — are launching “the Citizens Agenda,” a collaboration between The Guardian and NYU's Studio 20 program. Though the project will make use of some of the citizen-driven lessons of OffTheBus (and of The Guardian's multiple experiments in mutualized journalism), the citizens agenda will be above all an experimental space dedicated to determining how to get people’s voices heard in campaigns that, though they purport to be concerned with the people’s interests, all too often ignore them. The citizens agenda, the pair point out, is not a blanket attempt to end horserace coverage — campaigns are, fundamentally, races, and who’s winning them, you know, matters. Instead, they stress, it’s an attempt to disrupt the horserace as the “master narrative” of political reporting, to inject more perspective (and, for that matter, more data about the demand side of political journalism) into the conversation. “When people complain about what’s wrong with the coverage, there’s an opportunity to find out…. well, what should the candidates be discussing?”On the one hand, the citizens agenda is the digital — digitized — heir of civic journalism, the movement that (with Rosen at the helm) came to prominence in the 1990s and attempted to give individual members of communities more agency in the journalism that served them. On the other, though, while the citizen’s agenda is a kind of culmination of that movement — with, today, buy-in from one of the largest news organizations in the world — it’s also something entirely new. It will be, first and foremost, an experiment, Michel told me. They’re starting with an idea; they’re not sure exactly what will come of it. “It’s going to be an iterative process,” she says. There are two basic goals for the effort, Michel notes: first, the need to understand what people want to learn from and about political candidates — to gain an appreciation, as Michel puts it, of “how the public wants to contextualize the debates and discussion.” Campaigns are notorious for, and in a large sense defined by, their attempts to control narratives; a citizens agenda is in large part an effort to provide a community-driven counter-narrative.  Studio 20′s role in the project, Rosen told me, will be in part to act as an interactive team that will help with the inflow and engagement of users; students in the program will also conduct research and analysis and think through — perhaps even invent — features and tools that can foster that engagement in new ways, testing them out on The Guardian’s U.S. site. (Michel calls the students a kind of “independent brain trust.”) Studio 20′s role in the project, Rosen told me, will be in part to act as an interactive team that will help with the inflow and engagement of users; students in the program will also conduct research and analysis and think through — perhaps even invent — features and tools that can foster that engagement in new ways, testing them out on The Guardian’s U.S. site. (Michel calls the students a kind of “independent brain trust.”)“We don’t think that the direct way of posing the question, What do you want the candidates to be discussing as they compete for votes in 2012?, is always going to work,” Rosen notes. “Some answers to that question might have to come about indirectly: for example, in dissatisfaction with media coverage as it stands.” So “when people complain about what’s wrong with the coverage and campaign dialogue, there’s an opportunity to find out…. well, what should the candidates be discussing as they compete for votes in 2012?” “I think there is a kind of authority to be won here,” Rosen points out — a kind of permission for reporters to deviate from the expectations of rankings-based, rather than idea-based, coverage. “Of course, you have to be right, you have to be accurate, you have be listening creatively and well,” he says, and “with some subtlety and an awareness that each method has weaknesses and missing data.” Sampling science will certainly come into play. “This isn’t just reading numbers off a chart,” Rosen notes. “There’s a lot of judgment involved, obviously.” Helping to answer those questions will be Jim Brady and the collection of community papers at Digital First Media, which is partnering with the project to tailor the national findings to the local. “The concepts that they’re applying at a national level certainly don’t become less relevant at a local level,” Brady notes. Figuring out what the public wants out of coverage — and then figuring out how to implement it — can be, in fact, particularly powerful in community news. (That’s part of the reason the project is hoping to bring more local collaborators on board.) “There has to be a way to turn this into a full-circle feedback loop.”Though much of the Guardian’s experiments will likely involve online conversation tools like hashtags and surveys and the like, “it’s not an online-only feature,” Brady notes. At the local level, in fact, papers may well experiment with a citizens agenda approach in their print products — and with the kind of in-person debates and forums that were a hallmark of the early days of civic journalism. “We’ll use all platforms,” Brady says — “as in everything we do.” Still, though, there will be strategy involved, Brady points out. You have to be smart about both how you ask questions and how you make use of the answers. “It doesn’t work if it becomes citizens pouring out their hearts about the issues they want to hear about,” he notes, if “we can’t, as journalists, tie that to actual action by the candidates. Otherwise, it’s just like message boards that nobody responds to. There has to be a way to turn this into a full-circle feedback loop.” Finding that way will be crucial — and it will require, above all, an openness to both the wisdom of crowds and the political agency of average citizens. Which hasn’t always been journalism’s strong suit. The project will be, Rosen puts it, “a creative act of listening.” And it will be, in that, Michel points out, “a fairly dramatic acceptance of the knowledge and expertise that the public has” — not to mention a fairly dramatic act of humility on the part of the journalistic establishment. “The approach,” Michel says, “is to ask the American public: ‘What is it that you need? What can we do to help?’” Image by SpeakerBoehner used under a Creative Commons license. |