Nieman Journalism Lab |

- HuffPo launches a book club around augmented reading

- ProPublica.org goes responsive to better serve mobile readers

- 12 reasons the Argo Project will sail on — and some things NPR learned from the pilot

- From Nieman Reports: When deadlines are too tight for print, ebooks step in

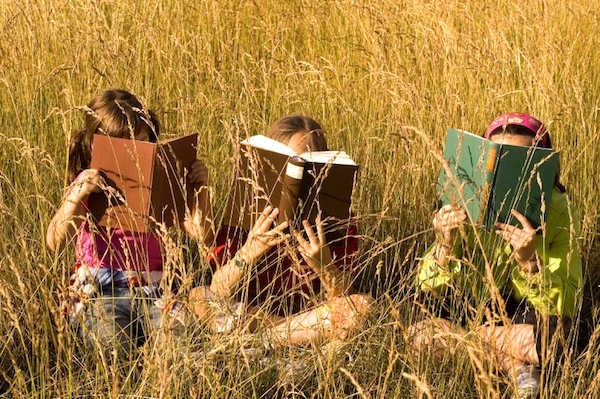

Posted: 13 Dec 2011 12:30 PM PST  Whether you’re a book-club type of person or not, there’s an understandable appeal to having people to talk to over those “OMG DID THAT JUST HAPPEN” moments when you’re reading something. Reading is an intimate pursuit, but it doesn’t take place in a vacuum — it’s a part of your everyday life, which means where you read, when you read, and what’s going on in your life all colors your reading experience. That seems to be the idea The Huffington Post is getting at with the introduction of its new Book Club, set to launch Jan. 3, which wants to make massive the idea of gathering in a gaggle to talk a book. The club will largely exist through HuffPo, but also on Twitter, Facebook, Flickr, and Instagram. That’s because, as Andrew Losowsky, books editor for the site, writes: “We want to know where and how you read, and what you can see and hear as you do so. We want to know where the story is taking you, and where your memories are taking the story.” “Normal” book club asks the group to gather and chat, enjoy some tapas, and a nice Chardonnay. The talk turns to the themes of a book, what it means, the author’s intent, the narrative structure and the resonance we feel between characters. HuffPo is taking that conversation and blowing it out, in, well, HuffPo style. As spokesman Mario Ruiz told me over email, “HuffPost will be the central hub for all these conversations, with designated ‘Big News Pages,’ liveblogs and more. We're also looking forward to taking conversations offline with readings, discussion groups and other events that we'll be hosting.” The Huffington Post wants to be the connector here. They see their value as a facilitator of the discussion by providing the structure for readers to share their reading experience. “We'll ask readers to tweet where they are as they read (#HPBookClub), and to solicit Facebook comments from their friends about book themes and ideas. We’re also launching a Flickr group (called HuffPost Book Club), where people can post images of where they are reading, and how that changes their reading experience,” Ruiz said. What the site gets out of this is what it almost always gets: traffic, eyeballs. It’s also not hard to imagine partnerships with publishers and authors, to cut deals for books or chats with writers. “It’s all part of our wider goal of starting and leading conversations, and our book club also has a specific goal of inspiring and encouraging more reading,” Ruiz wrote. The project in many ways is similar to Jeff Howe’s 1book140 club at The Atlantic, but perhaps more structured. 1book140 is more of a true crowdsourced book club, where the titles are chosen through the group. HuffPost’s book club is more of a guided experience, with a selection of books and authors, as well as planned meet-ups. (You can never stray too far from the comforts of brie en crôute and pinot.) Still, the value of the book club may be as an experiment in a kind of augmented reading. If you are reading a book about prohibition on a dock in Maine, or Jennifer Egan’s prize winner on a beach in Revere, Mass., (just to give two random examples), how does that change the way you digest a book? What about your state of mind? Is your perspective on The Marriage Plot different if you’re about to graduate from college? Does The Art of Fielding hit home if your favorite slugger is departing for a bigger contract on a different team? What we have now is more ways to catalogue our time with a book. We can take stock of a passage in the moment of a particular revelation, or that sad/euphoric rush that comes after reading the final sentence. What HuffPost realizes is that we’re already doing all of that. We’re snapping pics of random artifacts that remind us of characters and throwing them up on Instagram or tweeting about missing chunks of time lost racing through chapters. All of these external forces shape the way we read a book, what parts we latch onto the most and perhaps even the way we remember it. It only makes sense the book club, the catchall for all those insights and feelings born off the page, is adapting to what it means to read a book today. |

Posted: 13 Dec 2011 10:00 AM PST  In what some like to think of an age of apps — smartphone, tablet, or otherwise — it might seem hard to get worked up over a mobile redesign. But last week ProPublica rolled out a new look for small screens that’s pliable and flexible enough to fit across device types and that runs off of the same code as the big-screen site. Yup, it’s our old friend responsive design, more recently seen over at the much lauded launch of BostonGlobe.com. In what some like to think of an age of apps — smartphone, tablet, or otherwise — it might seem hard to get worked up over a mobile redesign. But last week ProPublica rolled out a new look for small screens that’s pliable and flexible enough to fit across device types and that runs off of the same code as the big-screen site. Yup, it’s our old friend responsive design, more recently seen over at the much lauded launch of BostonGlobe.com.ProPublica says their design is more “adaptive” than responsive. BostonGlobe.com has a half-dozen or so versions based on screen size, but ProPublica’s site only has two: below 480 pixels wide (which shows the mobile version) and above (which shows the desktop version). That’s because the new look is really for one audience: mobile web users, who ProPublica says far outnumber users of ProPublica’s iPhone and Android apps. How much bigger is mobile web than mobile apps for ProPublica? Scott Klein, editor of news applications, says it’s “an order of magnitude.” “We noticed that the audience on our regular old website, for people on mobile devices, was much larger than people using the app every day,” Klein told me. An interesting data point for any news organization trying to figure out how much to invest in building for multiple app platforms versus building a strong, fast, mobile experience. Admittedly, ProPublica’s not a standard news organization; its streams of stories are more organized by the specific investigative projects its reporters are working on rather than by what’s breaking at the moment. Those investigations would be hard to summarize in a push notification on your phone. The readership knows that, Klein said, which is why they developed a habit of checking on the ProPublica web site regularly, essentially porting over their behavior from reading on a computer or laptop. Those readers, Klein argues, want familiarity across devices. They also want to know that they’re not missing out on an interactive graphic, map, or other features from the full site that didn’t translate onto an app, Klein said. “This is just a way of making sure people who come to our site from mobile devices can see it really well and can read comfortably,” he said. They’re introducing simplicity for readers, but also, for the site itself, Klein said. To a degree, both the apps and mobile site were limiting some of ProPublica’s rich content because it either wouldn’t work within a mobile template or otherwise just wouldn’t look good, he said. Under the new site, things like maps for the Congressional redistricting series, Muck Reads or news apps like the database of physicians taking drug company money in Dollars for Doctors will be accessible. “Our hypothesis was, if we made it better for those people, they would come by more often, stick around, and find links to other material they find interesting,” Klein said. Even as ProPublica embraces a multi-platform approach with its new mobile site, they aren’t abandoning native apps, Klein told me. Though the readership is smaller compared to mobile browsers, the downloads of the apps remains fairly high and have a dedicated audience. “I can’t help but think there is a real future to this approach, making it so a website is ready for as many platforms as people want to look at it,” he said. |

Posted: 13 Dec 2011 08:30 AM PST   He continued: “That’s been interesting and valuable because…it feels like we’ve gotten sort of a microcosm of the broader universe of stations and the challenges they have to deal with.” In part one of this story, we reported on the experience of a dozen NPR member stations who participated in the $3 million Argo Project. Today, we focus on what the network learned from the project. Forgive the headline, but Matt Thompson made me write it.NPR hired Thompson in 2010 to help guide 12 member stations through the Argo Project, and along the way he shared his bits of blogging wisdom with all of us — from using numbers in headlines to embracing the Wiccan Rule of Three. (“The energy you send into the world will be returned to you three times over.”)  The project winds down at the end of this month, and, as I wrote yesterday, NPR sees it as a success. Thompson and the Argonauts will keep their jobs at the network next year. “We have right now both the desire and the opportunity to formally take what we’ve done with this pilot set of stations and spread it out as widely as we can within the system,” Thompson said. The project winds down at the end of this month, and, as I wrote yesterday, NPR sees it as a success. Thompson and the Argonauts will keep their jobs at the network next year. “We have right now both the desire and the opportunity to formally take what we’ve done with this pilot set of stations and spread it out as widely as we can within the system,” Thompson said.I talked to Thompson and his boss, project director Joel Sucherman, about what they learned from the two-year pilot. If Thompson coined the “Sully lead” — Andrew Sullivan’s noun-verb-blockquote style of bloggage — I shall present this article as a Thompsicle: a Matt Thompson listicle.1 1. Argo as network, not projectSoon after its inception in 2009, the Argo Project became the Argo Network.“When we originally set out to do this, the notion of a network was not really part of it,” Sucherman said. “Fairly early in the process, I think it was a couple of months in, it became clear that there could really be potential for the network to be greater than the sum of its parts.” Externally, the Argo sites promote one another. The ever-present “Network Highlights” box in the sidebar promotes the kind of unexpected discovery you might find on Morning Edition or All Things Considered. “It’s that serendipitous aspect of, I might be listening to a health reform story right now, but if it’s of a certain voice or quality, I would be just has interested in the story coming up next about higher education.” Internally, the network serves as a sort of support group for the reporters, none of whom had professional blogging experience before joining Argo. Many had limited web skills and no Twitter experience before the project started. “It was as much a technical network, and a network of ideas, as it was a content network,” Thompson said. Despite widely disparate topics, “we found a lot of interesting crossovers. We had, for example, at one point three different sites covering secure communities from three different angles, but sharing coverage, sharing ideas, creating reporting plans together in several cases.” NPR is bringing these lessons to projects like StateImpact, which resembles Argo on a grand scale. That project is a collaboration between the network and stations in all 50 states. So far eight states are up and running. 2. Argo as platformAll of the Argo sites run a modified version of WordPress which the NPR team built specially for the project. The platform includes tools to make life easier for bloggers, such as the link round-up tool we covered last year. All stations were required to use the Argo software, which meant the developers could push software updates to everyone at once. It also centralized the technical support.The Argo team was not interested in building a new content-management system from scratch. As he wrote in June, Thompson says journalism is moving toward the content management ecosystem. Digital news operations used to think of their CMS as their one-stop shop: a tool that would do everything one might want to do with one’s content…We’ve finally begun to accept that no single CMS can handle all of a digital news organization’s content functions. A good content management system today is designed to interact with lots of other software.Sucherman said the Argo team will donate the platform to the open-source community as soon as they finish shoring up the code. Long-term technical support will move to NPR’s Digital Services division. 2. Communicating across time zonesThompson has to communicate with 12 stations in three time zones, which is not easy. (“The Clay Shirky phrase totally holds true here,” he says. “Nothing will work, but everything might.”)“All public radio stations are very different,” Thompson said. “It’s not really akin to a newspaper chain and affiliates. Newspapers can be very different, but chances are they have very similar structures and hierarchies and what have you, and that’s so not true in the public radio universe.” Thompson has laid out in detail the many tools and approaches he uses to communicate on a daily basis: Skype, PiratePad, Twitter, Go2Meeting, Basecamp, the telephone, and face-to-face communication when he can swing it. When none of those tools suited a particular need, Argo created its own. Any news organization can do this: The team deployed OSQA, an open-source web app, for its technical support site. It’s like Stack Overflow for a niche group. Because it’s a question-and-answer site, not a discussion forum, threads are limited to questions of “How do I…” and not tangential debate. Like Stack Overflow, users can vote answers up or down, and a question is “closed” when answered. 3. Everyone is differentWhile Argo was pretty prescriptive about the daily workflow, encouraging exercises like the daily link round-up, a lot of differences emerged among the bloggers.Two of the biggest sites in the network, KQED’s MindShift and WBUR’s CommonHealth, are different in many ways, Thompson said. “MindShift is a daily site, where the focus is on significant banner pieces each day, where it includes a lot of contributions from freelancers,” he said. “The storytelling is almost a bigger part of CommonHealth, it’s a very carefully crafted, almost long-form narrative.” “Dropping a blogger into a traditional news organization and putting him or her in the last cubicle on the left, next to the kid with the Star Wars toys, is not the best way to do it.”CommonHealth gained attention for its deeply personal reporting, such as Rachel Zimmerman’s account of having painful sex after childbirth. That was not the plan, but Zimmerman continued reporting it in response to a tremendous community response. “As the project has gone on, I’ve actually defaulted to calling the bloggers reporter-editors, rather than reporter-bloggers, just because that subtle shift in language suggests something different to the folks that hear it,” Thompson said. “So much of what they do and so much of the skill set that they have, that they’ve developed over the year, is really as an assigning editor, too. It’s having the judgment, the news judgment, and the organizational capacity.” At Oregon Public Broadcasting, Ecotrope originally was meant to cover the environment of the Pacific Northwest — a big topic. ”As spring really got underway, we started talking about, What within that is our domain, what within that do we want to own?” Thompson said. “And Cassandra [Profita, the site's reporter] had become much more interested in issues of the grid, the energy grid, and how Oregon was going to achieve the renewable energy standards that it set out for itself leading up to 2020.” Shortly thereafter, Profita caught an unusual story: The local utility was shutting down wind turbines because there was too much energy on the grid. That became a dominant story on the blog over several months. 4. Institutional supportSucherman said Argo pushed bloggers to work with the radio journalists wherever possible. Zimmerman and CommonHealth co-host Carey Goldberg work closely with WBUR’s health care reporter, and they appear once a week on Radio Boston, the station’s local news show.The most successful Argo blogs, he said, are those that enjoyed the most institutional support — and that’s unrelated to the size and wealth of a station. What Sucherman learned could serve as a manifesto for any digital journalist today: “It’s very clear that dropping a blogger into a traditional news organization and putting him or her in the last cubicle on the left, next to the kid with the Star Wars toys, is not the best way to do it…I think it’s important the newsroom ultimately be a place where this person lives. This person needs to be of the newsroom. He or she should have support of an editor-level person. Also, you’ve got to have a buy-in from the executive team, as well. It can’t be something like, ‘Well, this is a newsroom experiment.’ “Ultimately, we all have to be looking at our futures. I come from the newspaper industry, and I don’t want to be in that position again where we’re staring into the abyss in the eleventh hour. I don’t think that’ll be the case for public radio, because public radio audiences keep growing. But I wouldn’t want to be in that situation.” Notes

|

Posted: 13 Dec 2011 07:00 AM PST  Two and a half years later I was stunned to learn that many of these same activists from the April 6 Youth Movement were now at the center of the revolution — organizing marches, coordinating efforts with other anti-Mubarak groups, and spearheading efforts to communicate a message of nonviolence. When the uprising began, I started contacting them to check that they were safe. By the second week I was writing a few short items for Wired.com and TheAtlantic.com. Editor’s Note: Our sister publication Nieman Reports is out with their Winter 2011 issue,”Writing the Book,” which focuses on the new relationships between journalism and the evolving book publishing industry. Over the next few days, we’ll highlight a few stories from the issue — but go read the whole thing. In this piece, David Wolman writes about his experience publishing on the platform of The Atavist. In the final days of Egypt’s revolution to overthrow President Hosni Mubarak, I was in the snowy mountains of Colorado for a vacation with the in-laws. There was no way I was going to unplug, though. Like most, I had been captivated by events in the Middle East. I also had something of an inside line. Every few days I received short correspondences via email or text message from two activists in Cairo I had gotten to know in 2008 while reporting a story for Wired about young people using social media to organize against Mubarak’s regime.On February 10 I received a text message from Ahmed Maher, cofounder of the April 6 Youth Movement: “Mubarak will go now. LOL.” By the next day Mubarak’s reign was finished. It was then that I knew I needed to go back to Cairo to write a fuller account of how Maher and his cohorts had transformed from rabble-rousers into full-fledged revolutionaries and chronicle what they had experienced in the lead-up to and during the uprising. I banged out a pitch and sent it to editors at four or five prestigious magazines. The rejections came in rapid succession: “This is a great proposal, but unfortunately we already have some Egyptian coverage in the works.” “It sounds like a fascinating and timely story, but it’s not one we can use right now.” “Thanks for giving us a shot. Given other things in our lineup, turns out there’s no way.” Digital publishing startup The Atavist had been on my radar; two of its founders are Wired alums, and I’d read a short piece about the project in Bloomberg BusinessWeek. The Atavist commissions and publishes long-form stories as ebooks for various devices — Kindle, iPad, Nook, etc. — or to be read on computers using e-reader software such as Kindle for PC. It’s strictly digital. No paper. If that fact makes you prickly, you should probably quit reading this essay. Keep reading at Nieman Reports » |