Nieman Journalism Lab |

- NPR’s StateImpact project explores regional topics through focused, data-driven journalism

- Is it just 8,000-word epics that make people hit “Read Later”?

- From Nieman Reports: In digital publishing, content drives length, not the other way around

- A web-first politics site for NBC News: Vivian Schiller on the launch of NBCPolitics.com

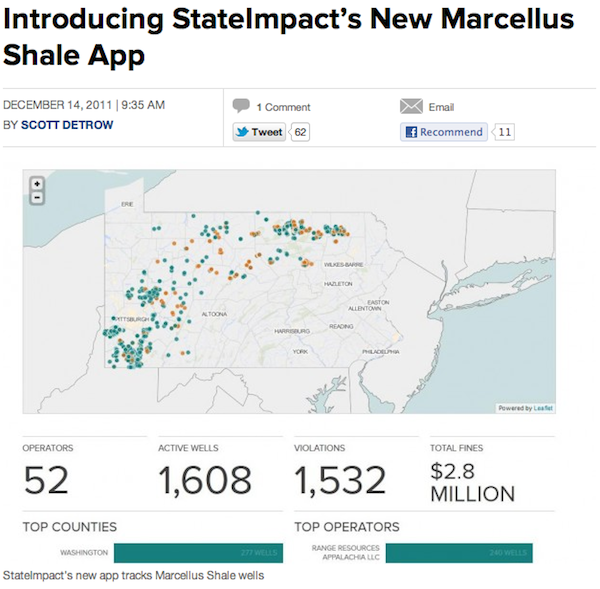

Posted: 14 Dec 2011 01:00 PM PST  Scott Detrow heard a rumor, and like any good reporter, he set out to determine whether it was true. Detrow, who has spent several years covering state politics and government for seven public radio member stations in Pennsylvania, had been told anecdotal claims that the expansion of drilling wells in recent years has drastically increased the burden on emergency service providers in the state. But the drilling industry, which opened 4,000 new wells in 2009 alone, is a controversial topic in Pennsylvania, and Detrow said both the opponents and proponents rarely agree on even the most basic facts. “I figured 911 records were a good place to take a look at that,” he told me in a recent phone interview. “So we got the 911 totals from the 10 counties with the most drilling and we saw seven of them did, in fact, see their numbers go up. And we did that as a framework to get into what that meant in a couple communities.” “We had to focus on what story we were trying to tell.”The end result was a two-part story. In the first, Detrow reported that 911 calls spiked by at least 46 percent in one of the counties after the introduction of new wells. “We're seeing more accidents involving large rigs," the head of one 911 call center told the reporter. "Tractor trailers, dump trucks. Vehicles — tractor trailers hauling hazardous materials. Those are things, two years ago, that we weren't dealing with on a daily basis.” In the second piece, Detrow explored the impact the increased burden on emergency services had on local county governments, many of which were having a hard time finding the funds to hire new EMS employees. “[County Commissioner Mark] Hamilton, who serves as the president of the County Commissioners Association of Pennsylvania, supports an impact fee on gas drillers to help offset the cost of more resources,” Detrow wrote. Compiling all this data took extensive man hours, and it paid off; Detrow managed to break a major story that settled a contentious dispute. But if he had tried to hunt down the data just a few months before, he would have run into a significant barrier: time. That’s because, up until recently, the reporter had spent the majority of his work week reporting on lawmaking in the state’s capitol building. “[Drilling] is something I’ve been covering over the last few years and it's something that's steadily become more of a main issue that I was spending more time on, but I was doing so through the framework of multiple stories a day on my beat and also having to cover everything else in state government.” Much of his reporting involved simply recounting what lawmakers were saying — and there were few opportunities to dive deeper into longer-term issues. In late June, though, Detrow joined NPR’s StateImpact. Billed as “station-based journalism covering the effect of government actions within every state,” StateImpact essentially takes the extensive resources of a national news organization and applies them to the local level. For its initial iteration, NPR member stations from around the country sent in applications, and from those eight were chosen to receive grants. The grants, in part, funded the hiring of two reporters for each state: one for broadcast and another for the web. NPR also hired a team of project managers, designers, and programmers to work at its D.C. headquarters; this team collaborates directly with each of the participating states to create platforms and other tools to mine deeper into a given topic. Because every state differs in its most important issues, each participating team focuses on a particular topic. The Pennsylvania StateImpact reporters, as you may have guessed, focus on energy, with a concentration on the impact of drilling. Three of the states (Florida, Indiana, and Ohio) cover education while the remaining ones (Idaho, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and Texas) report on issues ranging from the local economy to state budgets. “Why don't we work together so we can get something that's easy for us to use but also know it's going to be accurate?”To understand what the D.C.-based team brings to the equation, I visited them one morning at NPR’s headquarters. They started off the day with a meeting in which each member listed off his or her task for the week. In order to ensure the meeting didn’t stretch any longer than absolutely necessary, they all conducted it while standing. Afterward, I sat down with Matt Stiles, the database reporting coordinator, who walked me through a data-driven tool he and his colleagues had created to track the natural gas drilling in Pennsylvania. The map allowed one to drill down (no pun intended) into individual counties and wells to determine both how much fuel is derived from an area and the number of regulatory violations a particular well has seen. From start to finish, it took about three weeks to build out. “I spent time with Scott figuring out what data was available,” Stiles told me, and then worked with Detrow to determine the overall scope of the tool. “We had to focus on what story we were trying to tell.” Stiles has worked with government data for years, and so knew how to navigate the seemingly insurmountable barriers that can arise when trying to put it to use. “All of the data is available on the well,” he explained. “But it's in these sort of awkwardly-formatted spreadsheets. There was a process of me looking at that, Scott looking at it, and then going back to the state and saying, ‘This format doesn't really work for us. I could clean this data up and make it work with a lot of blunt force data cleansing, but why don't we work together so we can get something that's easy for us to use but also know it's going to be accurate?’” Kinsey Wilson, NPR’s senior vice president and general manager of digital media, said in a phone interview that NPR is launching StateImpact at a time when there’s an erosion of media coverage at the state level. “At the same time that a growing number of significant issues are moving through state governments as things have gotten somewhat more gridlocked at the federal level, we're seeing a variety of issues — environmental regulation, education, and so forth — [becoming] the subject of state legislation,” he told me. While he sees a particular need for in-depth reporting around some of those issues, NPR didn’t simply want reporters to conduct statehouse legislative coverage: Plenty of local news outlets are still devoting resources to that. Instead, the network saw an opportunity with issues of consequence in selected states. “We’ve armed them with skills that they'll be able to use for the rest of their careers, we hope.”StateImpact also signals a shift in how local NPR member stations operate. For years, they offered some local programming, but mostly acted as distributors for national NPR content. “In the digital era, if they are to continue to thrive and reach the kind of audiences they reach today, they're by necessity going to have to offer a news package more directly relevant to their audience,” Wilson explained. “The national coverage can be obtained at any number of outlets directly, so the big picture in this effort is to help stations extend their local relevance. They’re uniquely positioned to do so. They’re among the few remaining genuinely locally-owned news institutions in most communities. They have real connections in the community.” Elise Hu sees other benefits to the StateImpact platform. Hu, the editorial coordinator for the team, oversees the digital editorial vision for all the participating states, and also ensures that the project’s content management system aligns with the organization's goal to “[give] our readers the Wikipedia-like introduction to the topics that they might be encountering.” Part of her job involves traveling from state to state to meet with reporters directly. In fact, when I spoke to her, she was sitting in an airport, about to head to Indianapolis for a convening of StateImpact's three education states — Indiana, Florida, and Ohio. “I think one of the great takeaways of this project, even if StateImpact goes away — which I hope it won't, but even if it does go away — is that there are 17 member station reporters that might not have otherwise been exposed to this sort of training or this data-driven reporting,” she said. “We’ve armed them with skills that they'll be able to use for the rest of their careers, we hope.” Scott Detrow agreed with this notion. “My knowledge of Excel beforehand was pretty minimal, and we had several training sessions on just using that as a reporting tool,” he said. “That is just really helpful in covering an issue where there are all these enormous spreadsheets you have to go through with the reporting.” Earlier today, Detrow and the team released an interactive web app that focuses on the state’s Marcellus Shale. An app like that, he said, is “not something we would have thought to have done beforehand, and being able to work with people who have the skills to put that together is just great.” It will be interesting to see how StateImpact develops, especially as it opens up to more states. (It hopes to operate in every state in the country.) But perhaps even more interesting is seeing how NPR will continue to incorporate the lessons learned from this experiment into the rest of its news coverage. With the changing digital media landscape in journalism, fraught with declining revenues and fleeting audiences, no experiment is carried out in a vacuum. And, as Hu pointed out, many of the issues covered in these individual states are of national relevance. “StateImpact is essentially acting as a lab to see how agile we can be, how quickly we can churn out an app,” she said. “And the fact that we were able to go from concept to deployment within a month will be a good story to tell for other members of the digital team at NPR to push that forward as an organization in data app development.” |

Posted: 14 Dec 2011 09:30 AM PST  In this week’s Monday Note, Frédéric Filloux wrote a piece on the ecosystem of “smart people curat[ing] long form journalism,” which he described as including Longreads, Longform, and Instapaper. Which, if you think about it, is an interesting grouping. Longform and Longreads are both curators of excellent, long works of journalism and nonfiction; they identify long stories and link to them. They’re fundamentally editorial products. Instapaper (along with its competitor Read It Later) is a tool, a method for saying, “I don’t want to read this now — so save this article in a pleasing format offline, in a place where I can come back to it later.” It’s a technical product; it deals with raw gibberish and finely honed prose equally well. Instapaper-like tools and Longreads-like services get lumped together a lot because, I’d argue, of a story we like to tell ourselves about long-form journalism, something I like to call the Long-Form Longing. People who care about journalism — particularly those of us who’ve shifted 95-percent-plus of our reading online — love to valorize long-form journalism. We root for efforts that seem to promote the kind of work we fear might be getting lost in a blizzard of tweets. Here’s one of my favorite short pieces by Internet superstar and ex-Harper’s editor Paul Ford: I was out for a drink with a friend who works for a womens’ magazine. She does not love her job, mostly because she is in charge of compiling yoga recipes and candle news (a column called Candletips) for the front of the book. "I just commissioned a 2,200-word piece," she said, "with the provisional title Hollywood’s Neti Nuts: Star Sinus Secrets." She took a long draught of red wine and closed her eyes for a moment. "So, that. But if you look in the back of the book, we are still publishing long-form journalism."The popularity of tools like Instapaper and Read It Later give us comfort — because if people are using them to read things later, it stands to reason that those things must be the kind of long-form work that we admire. The thing is: that comforting vision doesn’t seem to be particularly true. Remember last week when Read It Later released that great dataset on which publications and authors were saved the most often in its system? We wrote about it and, like others, noted that the most-saved authors often worked at blogs like Lifehacker, Gizmodo, Mashable, and Techcrunch. Fine publications all, but John McPhee they ain’t. This seemed to surprise Filloux: Great writers indeed, but hardly long form journalism. We would have expected a predominance of long feature stories, we get columnists and tech writers instead.“We would have expected” is the Long-Form Longing in a nutshell — the idea that, now that we have the tools to shift reading from length-averse environments (sitting at your desk at 10:30 a.m., avoiding an Excel spreadsheet) to length-friendly environments (on your couch, sipping merlot, iPad in hand), people will want 8,000 words on the history of grains. Or at least a long New Yorker feature. But the data doesn’t, at first glance, seem to back that up. Here’s another, more thorough dataset that illustrates the point even better. Back in September, I moderated a panel on new platforms for long-form journalism. I wanted to have some new data for the introduction, so I emailed the nice folks at Read It Later to see if they could share with me the range of word counts of articles saved using its tool. How many were short quick blog posts, and how many were Vollmanesque epics? First, some details about the data they sent me. (Thanks again to Nate Weiner and Matt Koidin for their help with it.) This is data from articles saved using Read It Later from March to May of this year. It only includes articles — that is, YouTube videos and other non-article URLs are scrubbed out of the data. And it ignores articles that are either shorter than 100 words or longer than 10,000. Here’s the chart:  (Here’s that same chart, much bigger.) The x-axis is word count — how long the articles were. The y-axis is the number of articles. The blue area represents how many articles were saved; the red area represents how many articles were actually read after they were saved. (And here “read” means “ What you can see here is that, by far, the largest number of articles that are being saved are short — under 500 words. The number of articles saved drops off quickly at word counts higher than that. (The jagged green line represents the ratio of read to saved — that is, at a given word length, how many of the saved articles later get read. As you can see, it’s lower for longer articles, but not remarkably so. The green line is the only one on the chart for which the percentages on the right side of the chart apply.) Now, do more people read longer pieces because of tools like Instapaper and Read It Later than they would without them? Sure! I know I do. And while this chart seems heavily weighted toward shorter pieces, a chart showing the entire universe of save-able online content would no doubt be far more skewed toward brevity. But the evidence seems to be that people find time-shifting useful regardless of length, and that using these tools for really long work is more of an edge case than common usage. It appears the user’s thought process is closer to “Let me read this later” than “Let me read this later because it’s really long and worthy.” And that, to me, means that journalists should learn to separate the promotion of long-form from the promotion of time-shifting. Both are useful ideas, but the Venn diagram of the two is far from a perfect overlap. Notes

|

Posted: 14 Dec 2011 07:00 AM PST Editor’s Note: Our sister publication Nieman Reports is out with their Winter 2011 issue,”Writing the Book,” which focuses on the new relationships between journalism and the evolving book publishing industry. Over the next few days, we’ll highlight a few stories from the issue — but go read the whole thing. In this piece, John Tayman writes about his thinking behind starting Byliner. How many words do I have? It’s a question I’m accustomed to asking whenever I write a story. Sometimes I ask it of myself, more often of my editor. Before I started writing this piece, I asked the editor of this magazine for a length. “You’ve got 1,000 words,” she replied. “You’ve got 1,000 words,” she replied.That’s an arbitrary word count, of course, since I could tell the story of our eight-month-old digital publishing effort in fewer words. Or I could tell it in more. With my words destined for Nieman Reports’s print pages — and for its website — it’s natural for the editor to think about how many words she wants and what visuals might accompany them. This is a sensible approach and until recently was how publishing worked, whether in a magazine or a book. Editors assigned story lengths, then slashed or stretched what got delivered to a workable word count, even when that count might not serve the story well. Over the years, I’ve often been the one doing such slashing and stretching. It’s never fun. Some stories escaped unscathed, but most suffered — and their writers suffered — simply because a few magazine ads went unsold or the marketing department felt a fatter spine would sell more copies in bookstores. Oh, we waxed poetic about “letting the story find its natural length.” But deep down we knew it wasn’t possible. A story that needed 10,000, 20,000 or even 30,000 words to be properly told inevitably fell into publishing’s dead zone. This represented the vast wasteland of impossible-to-place stories that were longer than magazine space permitted and shorter than a book was thought to be. In January 2009, a year before the iPad was launched and two years before Amazon introduced Kindle Singles, I was chatting with some writers and editors about an idea for a company that would bring stories that fell into that dead zone to life. Our idea was to create a new way for writers to be able to tell stories at what had always been considered a financially awkward length. Such articles — at this longer length they were likely to be told as narrative accounts — would be reported and written swiftly, not unlike a magazine piece. We’d sell them on digital platforms as ebooks. Keep reading at Nieman Reports » |

Posted: 14 Dec 2011 05:00 AM PST  NBC News keeps its political reporting in lots of different places. There’s Chuck Todd on Twitter, in the evening with Brian Williams and the Nightly News Crew, online at MSNBC’s First Read, or your Sunday morning coffee date with David Gregory on Meet the Press. That diffusion is part of why today they’re launching NBCPolitics.com, a site that brings all of that news under one digital roof. NBC News keeps its political reporting in lots of different places. There’s Chuck Todd on Twitter, in the evening with Brian Williams and the Nightly News Crew, online at MSNBC’s First Read, or your Sunday morning coffee date with David Gregory on Meet the Press. That diffusion is part of why today they’re launching NBCPolitics.com, a site that brings all of that news under one digital roof.NBCPolitics.com will be something of an NBC News aggregator, pulling together the work of on-air reporters like Kelly O’Donnell and Andrea Mitchell, as well as the mostly off-air types like the embedded reporters checking in from the campaign trail. They plan on offering video, directly from their family of shows as well as reports and interviews exclusive to the web. But the site will also see a new collection of social news, maps, and a one-of-a-kind candidate tracker via Foursquare. As NBC News chief digital officer Vivian Schiller told me, unification is an important aim for NBC News, which feeds into a sometimes confusing collection of network, cable, and web properties. “It’s a way for people to have one destination, where they can get all the political coverage from all of our political reporters in one place, from all of the shows,” she said in a phone conversation. “One of the main impetuses [for the site] is we have so much strong politics coverage both on television and on the web, but you have to seek it out.” It’s really a reflection of looking at the web as the web, as opposed to looking at the web as an extension of television only.It’s also an acknowledgment that the division of coverage by TV show — Maddow here, Williams here, Morning Joe here — doesn’t line up perfectly with an online audience that isn’t bound by broadcast times. (“Pretty much most of what we have online has been organized around television shows,” Schiller said.) If you like news with a side of features and celebrity interviews, here’s The Today Show. If you want inside politics with lawmakers, analysts and reporters debating each other, there’s Hardball. Looking for an overview of domestic and international news? Try NBCNightlyNews.com. Each site serves a purpose and reaches a specific audience, but function largely as a companion to what’s on TV. “If someone is a political junkie, we don’t want them to necessarily have to think about what is the television show that I’m looking for,” she said. “We want them to have the full power of all the resources of NBC News available to them on politics in a way that is easy for them to find and easy for them to digest.” Schiller said they saw a need to step outside of the normal TV model and create something “webbier,” in her words. “It’s really a reflection of looking at the web as the web, as opposed to looking at the web as an extension of television only,” she said. Video drives traffic It’s been close to six months since Schiller joined NBC after parting ways with NPR, and she’s been busy at the Peacock Network, most recently beefing up her social media and engagement team. The development of NBC Politics marks her biggest project yet, and in many ways echoes some of her work at NPR, like investing in research, new technology, and a news platform separate from your primary channel. It’s been close to six months since Schiller joined NBC after parting ways with NPR, and she’s been busy at the Peacock Network, most recently beefing up her social media and engagement team. The development of NBC Politics marks her biggest project yet, and in many ways echoes some of her work at NPR, like investing in research, new technology, and a news platform separate from your primary channel.But NBC Politics won’t move too far away from the bread and butter of broadcast. Schiller says there will be plenty of video, from reports from the road to interviews from TV programming. Video is what the audience expects from NBC News, she said. According to comScore the MSNBC Digital Network (which includes MSNBC.com, Today.com, NBCNightlyNews.com and more), saw more than 161 million video streams in October, putting it ahead of CNN and The Huffington Post for news videos. “Of course we’re competing with other news organizations around politics, but the strength that we have really above all others is the fact that we have video,” she said. Making news social through partnershipsThe network is trying to press its advantage through social media in reporting as well as connecting the audience, journalists and politicians. The NBC News embeds, a group of young reporters called on for on-air as well as online duties, are active on Twitter most days sending minute-by-minute dispatches from the different candidates. Next month NBC News is co-hosting a Republican presidential debate with Facebook, that will be broadcast on TV and online. And in one of the most interesting mashups, they’e partnering with Foursquare for a feature they’re calling Campaign Check-ins, where readers can follow candidates and reporters as they check in from the high school gyms, diners, and other obligatory locations of the primary season. Schiller said they also need to make themselves available through whatever platform the audience is using: “I’m a big believer in fishing where the fish are.”That strategy seems to be the backbone of NBCPolitics.com, which Schiller ultimately believes can serve audiences across different platforms, as well as news preferences. If you’re a fan of Chuck Todd, there’s something for you on the site, and if you’re someone looking to stay current on the big themes in the news of the day, you’ll be covered there too. What they’re shooting for is NBCPolitics becoming a kind of audience multiplier for NBC News, a site that can draw in the preexisting audience loyal to shows and personalities, as well as the crowd looking for general election news and the political operatives. “Our goal is to be the number one most valuable source for politics on the web, period. Not just among television news organizations, but among all news organizations, for Election 2012,” Schiller said. |