Nieman Journalism Lab |

- In the Netherlands, a magazine experiments with “social distribution” (and they don’t mean retweets)

- This Week in Review: Snowden’s flight continues, and the Tribune Co. cuts and runs from print

- It’s the engagement, stupid: Jim Chisholm says newspapers need to do more to earn attention

| In the Netherlands, a magazine experiments with “social distribution” (and they don’t mean retweets) Posted: 12 Jul 2013 10:50 AM PDT Every workday in Mumbai, 5,000 home-cooked meals make their way from homes to offices at midday via a network of “culinary couriers” called dabbawallas. Single meals often pass through a dozen hands and as many distribution zones on their way to their destinations, where workers wait for meals made fresh at their homes. The phenomenon is chronicled in the first issue of Works that Work, a magazine published in the Netherlands that has become a distribution experiment of its own. Focusing on design and “human creativity,” the small magazine has found a way to get noticed globally by creating a beautiful digital edition as well as a creative way to distribute its print copies—gaining a lot of ever-coveted user engagement in the process. The magazine’s founder, graphic designer Peter Bil’ak, calls it social distribution. It works like this: Fans of the magazine can ask their favorite bookstore to sell copies for a fixed price. If they agree, the reader then purchases 10 or more copies of the magazine at half price (print copies cost $20, while the digital version costs $10), and then sell them on to the bookstore at a price higher than what they paid but lower than the cover price. Reader/distributors keep the difference. It’s using readers to do the jobs of distributors, which is not something that many other than die-hard fans will be willing to do. But it also keeps costs lower than they would otherwise be for a small publication. “We looked at these logistic networks and we thought, if the magazine is about rethinking, about a different way of looking at design, this is how we should operate as well,” Bil’ak said. It’s worked out well on a small scale for Works that Work, which published just 3,500 copies of its second issue in July. Half of those print copies were sold to individual readers, and the other half were sold in batches to readers and made their way to bookstores (and friends’ homes). Most of the 32 bookstores to take the magazine’s first issue are in Europe, but they also include spots in Indonesia, Hong Kong, and elsewhere. That doesn’t include informal distribution points or schools, like the College of Creative Studies in Detroit, where the magazines are delivered directly. Social distribution has made for a surprisingly global publishing model for a small-scale print magazine, with modest numbers of copies “circulating” in Asia and South America. At the traditional art and design magazine he worked at before founding Works That Work, “we never had any sales in India, in Russia, in Brazil,” Bil’ak said. “They’re just trying to reach English-speaking countries — maybe Germany, the rest of Europe. It’s too costly, not worth the effort.” The magazine’s global reach was carefully planned, down to the weight and binding of each copy to ensure ease of shipping. (“We were designing envelopes before there was even a magazine,” Bil’ak said.) Those concerns, though, weren’t even on Bil’ak’s mind when he started the project with nearly 30,000 euros raised by crowdfunding. Only after he raised the money did he ask the contributors: How do you want to read this thing? “I didn’t mind if it was going to be an ebook or online or print. I was hoping for the print…but I didn’t really know,” he said. The verdict was in soon enough: more than 90 percent said they wanted to read either in print or both in print and digitally. “It’s really readers who made the choice to make it a physical product, and we had to figure out how to get it to them,” Bil’ak said. Their business model, though, isn’t quite as fixed. The magazine is still figuring out how it’s going to pay the bills. Its first issue included some prominent advertising, but Bil’ak tried to make the second issue work with only donations, which ended up only covering about half of the magazine’s expenses. (All contributors are paid; Bil’ak is not.) Another way to foster user engagement is to have fans of the magazine host events for like-minded readers and sell copies, which is what happened a few months ago at a bar in Sao Paulo where designer Bebel Abreu helped sell 42 copies. She’s planning a second event in August. “It’s something I like to read and I’d like my friends to have this experience as well,” she explained. “It’s not for the money. It’s because it’s cool.” A debate over staples — yes, staples — illustrates that back-and-forth with readers. Many of its design-obsessed readers were not impressed with the first issue’s binding, which included visible staples. A 627-word blog post from Bil’ak followed, explaining the intricacies of saddle-stitch and cold-glue binding and including this video. Also following: a change to the binding. “To create a community around the magazine, that’s equally important, that people feel a part of it, people feel engaged,” Bil’ak said. |

| This Week in Review: Snowden’s flight continues, and the Tribune Co. cuts and runs from print Posted: 12 Jul 2013 07:30 AM PDT Snowden’s defenders and detractors: U.S. National Security Agency leaker Edward Snowden’s attempts to find safe harbor have stretched into their fifth week, with three Latin American countries — Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Bolivia — formally offering him asylum. Despite some conflicting reports, Snowden hasn’t yet picked Venezuela, though The Guardian’s Glenn Greenwald, one of the journalists he leaked to, suspects he will. Hilary Sargent has a good summary of Snowden’s options at this point, and the Russian TV network RT has some useful running updates on the situation. Two news organizations — Der Spiegel and The Guardian — published parts of interviews with Snowden from just before he revealed himself as the NSA leaker. The free speech site Cryptome has the fullest version of Der Spiegel’s interview, while GigaOM’s Mathew Ingram noted that Snowden told The Guardian the NSA has direct access to tech companies’ servers, something those companies have denied. (Days later, Greenwald reported that Microsoft has worked closely with the government to give it access.) Snowden also gave another interview to Greenwald in which he denied giving documents to Russia and China. In The Washington Post, Pentagon Papers leaker Daniel Ellsberg defended Snowden’s decision to flee the U.S., arguing that the way the government treats these cases has changed substantially since Ellsberg decided in 1971 to stay and stand trial in the U.S. Gawker’s Hamilton Nolan echoed the point, saying Snowden doesn’t owe anything to the moralists who would have him turn himself in. (Reuters’ Jack Shafer did advise future leakers not to go solo as Snowden did, however.) Snowden enjoyed support from other corners as well: A new poll showed that a majority of Americans see him as a whistleblower rather than a traitor, while NYU’s Jay Rosen chronicled the gains in public knowledge that have come out of the aftermath of Snowden’s leak. Snowden’s personal story isn’t as important as that of his revelations, Rosen said, but it is relevant. And the Boston Review’s Archon Fung argued that the Snowden affair is an indictment not of Snowden himself, but of broken governmental institutions and a compliant American press. There was one very prominent critic of Snowden’s (and Greenwald’s, and WikiLeaks’): The Washington Post’s Walter Pincus, who wrote a column questioning whether WikiLeaks was the organization directing Snowden to get documents from the NSA, connecting Snowden with journalists, and generally masterminding the entire affair. Greenwald fired back with a list of inaccuracies in the story, then questioned why a correction hadn’t been posted after Pincus had privately acknowledged the errors to him. Talking to The Post’s Erik Wemple, Pincus conceded a few points but defended a few others, and The Post finally corrected the column Wednesday, though Mathew Ingram chastised the paper for how long it took.

Running away from print, toward TV: After months of speculation about Tribune Co. selling off its newspapers, the company announced this week it will split the papers off into a separate company. Tribune’s eight newspapers, led by the Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, and Baltimore Sun, will become Tribune Publishing Co., with its broadcasting assets, including its 42 local TV stations and the cable channel WGN America, remaining part of Tribune proper. The Chicago Tribune has the basics of the split, while The New York Times put the move into context, explaining that it’s meant to avoid some taxes and it’s part of a larger quarantining of print by major media companies, such as News Corp. and Time Warner. Meanwhile, the people everyone’s talking about as a potential buyer for Tribune Co.’s newspapers, the Koch brothers, said a bid was “possible.” Here at the Lab, Ken Doctor wrote a strong analysis of the move: Tribune Co., he said, still plans to sell the papers, and will keep all of its reliably profitable assets under Tribune Co. flag. The main goal: ”make sure the newspaper assets don't muddy the big broadcast play, and set the clock to do that. Chart the path. Buy some time. Hope for the best.” It’s the same strategy laid out by industry analyst Alan Mutter, who explained why media companies are cutting and running on print. As Doctor put it, “Metro newspaper companies are finding they are no longer creatures of the market.” The other side of this retreat is a move deeper into TV, as both Tribune and Gannett have recently bought substantial local TV properties. Poynter’s Rick Edmonds gave some good background on the newfound attractiveness of TV stations. The New York Times’ Brian Stelter explained why swing-state stations — with their political advertising prowess — have become especially hot properties, and The Times’ David Carr issued a caution about their cost-cutting and revenue-declining downsides. Mutter was similarly wary: In a pair of posts, he laid out the reason for the TV grab (it’s simply been a more reliably profitable business than print) and warned that as smart TV and multiplatform viewing rise, the local TV industry could collapse as newspapers did.

A collusion ruling on ebooks: A U.S. federal judge ruled this week that Apple colluded with five publishing giants to raise ebook prices as a way to break up Amazon’s dominance in that market. Reuters and The New York Times have good explanations of the case and its possible fallout, while paidContent Laura Hazard Owen has a shorter primer, including a note that consumers aren’t likely to see any change in ebook prices. Jon Brodkin of Ars Technica wrote a more thorough explanation of the judge’s rationale in his ruling: The central aspect was a clause in Apple’s contracts with publishers that didn’t allow them to sell ebooks for a cheaper price than Apple’s, forcing Amazon to raise its prices and the publishers to adopt a different selling model (the agency model). John Gruber at Daring Fireball also pointed out that Steve Jobs’ 2010 statement to All Things D’s Kara Swisher was cited by the judge as a key piece of evidence of Apple’s intentions. The Wall Street Journal’s Jacob Gershman outlined the road ahead for Apple after the decision, and All Things D’s John Paczkowski talked to legal scholars about why Apple’s appeal will be difficult. Still, several others said that the villain in this case may not have been Apple, but the publishers. Forbes’ Jeff Bercovici talked to a legal expert who argued that it was the publishers who were conspiring to raise prices even further, with Apple successfully getting them to institute price caps. At The Guardian, Dan Gillmor detailed how publishers’ greed had led him to give up on ebooks, also noting that the publishers put themselves at Apple and Amazon’s mercy with their obsession with digital rights management. GigaOM’s Mathew Ingram expanded on that point, arguing that their insistence on DRM has ultimately hurt them. “How much larger could the ebook market potentially be if publishers hadn't built those DRM walls around their content and given Amazon and Apple the only keys to unlock them?” he wrote.

One of CNN’s most regular critics, NYU’s Jay Rosen, announced that he was done scrutinizing the network, saying that no one in journalism cares that CNN is now essentially tabloid TV, and by now, neither does he. Several people seconded his points: At Gawker, former CNN executive Sid Bedingfield argued that CNN has lapsed into a “Team Zimmerman vs. Team Trayvon” entertainment-TV approach, rather than anything resembling responsible journalism. Joshua Keating of Foreign Policy said CNN shouldn’t be thinking of foreign stories as eat-your-vegetables material. And The New Republic’s Laura Bennett said it’s not just that they’re doing tabloid journalism, but that they’re not even making it interesting. Inside Cable News, however, urged Rosen not to give up on CNN yet, calling the Zimmerman trial an outlier. And Adweek’s Sam Thielman wrote a rosy report about the optimism at CNN regarding the financial fruit borne from the network’s shift from the political to the personal — which is more or less why Rosen is giving on CNN in the first place. Reading roundup: Several other stories to watch this week: — The trial of WikiLeaks source Bradley Manning continued this week as the defense finished its case, and one defense witness drew particular attention: Harvard law professor Yochai Benkler, who testified that the news media had generally portrayed WikiLeaks as a legitimate journalistic organization before Manning’s leaks were published, when that image flipped to an enemy of the state. You can read Benkler’s testimony in two posts (starting on page 15 of the first). Both Mathew Ingram of GigaOM and Jeff Jarvis of The Guardian wrote on Benkler’s testimony about the importance of determining who is considered a journalist. — A couple of developments this week in response to the tape released last week in which News Corp.’s Rupert Murdoch acknowledged knowing of journalists’ bribes to public officials: Police want the tape as part of their investigation into the bribes, and he will testify again to a parliamentary committee about the phone-hacking scandal. — In the midst of its political unrest, Egypt’s new leaders are targeting the news media in their efforts to suppress dissent, shutting down TV stations and arresting journalists. They also kicked Al Jazeera out of a press conference, as other journalists from Al Jazeera resigned in protest of biased coverage in Egypt. — A Gallup poll found that despite the continued growth of the Internet as a news source, TV still serves as Americans’ top source of news. PaidContent’s Mathew Ingram had more details on the poll and especially the diminishing role of print it revealed. — Finally, a few in-depth looks at several aspects of the state of journalism: The J-Lab published a wide-ranging report on local public broadcasting, the Lab ran a case study from Dan Kennedy in locally owned for-profit community journalism, and The Atlantic’s Riva Gold wrote a incisive analysis on the financial factors contributing to the recent decline in newsroom diversity. Photo of Snowden protester by Steve Rhodes used under a Creative Commons license. |

| It’s the engagement, stupid: Jim Chisholm says newspapers need to do more to earn attention Posted: 12 Jul 2013 06:30 AM PDT “There is no statistical evidence anywhere that print circulations are declining because of the Internet. I’ve said this many times, and everybody tells me I’m talking complete rubbish,” says Jim Chisholm. “Circulations in the U.S.A. were declining long before anyone invented the word ‘WWW’…The cause of decline in analog consumption is more to do with changes in society than it is to do with the emergence of the Internet.” That argument — that the decline of newspapers’ fortunes has roots much deeper than the proliferation of screens in our lives — may go against the flow, but Chisholm, a Scottish newspaper consultant, believes it’s important to acknowledge it if newspapers are going to thrive. He presented his ideas at this year’s WAN-IFRA newspaper congress in Bangkok (which Frédéric Filloux deftly summarized), making a case that online content is, at this point, no replacement for print when it comes to reader engagement — and, therefore, advertising revenue. Shallow engagementHow newspapers are faring online depends on how you look at the numbers, which Chisholm draws from comScore and Nielsen. On one hand, newspapers are among the most popular destinations for Internet users in the United States — 61.5 percent of Americans with an Internet connection visited a newspaper’s website in May, for instance. But that same data says that Americans often don’t go much further than a newspaper’s homepage and don’t spend much time actually reading its content. Newspapers represented just 1.5 percent of pageviews, 7.9 percent of total visits, and 1.7 percent of the total time that Americans spent online in May, Chisholm says. “The central point of my argument is that newspapers are reaching out to people very successfully, but the reason they are failing commercially, is because people are not visiting newspapers [online] in any great number,” Chisholm said. “Whereas with a printed newspaper, you tend to read it for about 25, 30 minutes, the digital newspaper you tend to read for only five…The net result of this is, when you compare print and digital consumption — by that I mean times visited, number of pages visited, time spent with each page — the consumption level worldwide is about five percent that of print.” (Longtime Nieman Lab readers may remember Martin Langeveld making a similar argument back in 2009 — that print engagement with newspapers was so much more intense than its online equivalent that print was still wildly dominant in how people engaged with newspaper content.) Chisholm’s argument is that this is a cultural trend — that as people fill their days with recreational activities on- and offline, there is little time left to read the news of the day, in any format. And what time is spent reading newspapers is geared toward only the news that is relevant to the individual — as Ethan Zuckerman writes in his new book Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection, “Our challenge is not access to information; it is the challenge of paying attention. That challenge is made all the more difficult by our deeply ingrained tendency to pay disproportionate attention to phenomena that unfold nearby and directly affect ourselves, our friends, and our families.” Here’s one chart from his Bangkok presentation, showing how reading habits by age cohort have shifted over time in the U.K. for national newspapers. In the ’70s and ’80s, young people were actually the age group most likely to be reading a paper. That trend began to shift by 1990, and by 2000 — a time when the Internet was still quite young as a mass consumer medium — young people were already giving up the habit.

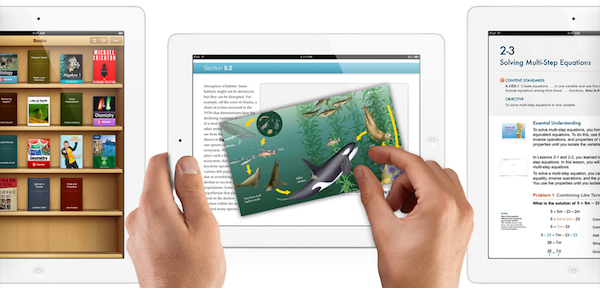

“This is audience-consumer behavior,” Chisholm said. “The problem is that newspapers compete as much with the golf course and the restaurant, and people’s lifestyles, as they do with digital media. I think the nature of news is changing. Today news is far less serious and far more celebrity-based, and Twitter and Facebook feed themselves into that in a very precise way…The biggest cause of decline in circulation is purchase frequency. People are still reading and buying newspapers from time to time, but they buy them less often, and that’s a challenge.” The tablet hopeSo if people — particularly young people, he says — are growing less engaged with news, as Chisholm argues, what’s the right path of investment for newspapers? He’s criticized newspapers for shifting too much of its investments toward digital — not because print will last forever, but because allowing the print product to decline has accelerated circulation losses — which have in turn meant there’s less revenue available to invest in digital. (Most newspapers still generate only around 15 percent of their revenue from their digital products.) In a piece for News & Tech last fall, he argued the place to push is tablets:

Tablets users are more likely to engage with ads, and seem to be one of the few digital solutions that could rival print ad consumption, Chisholm believes. “What you’re basically paying for is bang for buck, isn’t it? And you still get more bangs in print, so money remains in print. And the challenge for newspapers is to get people to visit more often, to visit more content, and spend more time with it,” he said. “There’s a direct correlation between the level of consumption and the level of advertising revenue generated.” Tablets can help there, he argues, in part because they offer benefits similar to both print and digital experiences — you can read a package of content from front to back or you can surf around, and new navigation concepts can encourage deeper engagement. More and better marketing can help, too. In 2009, Chisholm worked with the Newspaper Association of America to issue a forecast on what the media industry will look like ten years into the future. “Things have turned out worse than I predicted,” he says now. “The point of inflection, as I called it, where Internet revenues grow faster than [print] advertising revenues decline, is taking longer than I expected. But I still think that point will come.” Photo by Mike Bailey-Gates used under a Creative Commons license. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |