Nieman Journalism Lab |

- In Burma, newspapers are going daily, but the transformation to watch may be in mobile

- Changing trains: The Local East Village, NYU’s hyperlocal blog, moves from The New York Times to New York magazine

- This Week in Review: British papers fight new regulations, and Pew’s (mostly) dire look at news

- From Nieman Reports: When going undercover, an ethics of utility versus an ethics of rules

| In Burma, newspapers are going daily, but the transformation to watch may be in mobile Posted: 22 Mar 2013 10:15 AM PDT

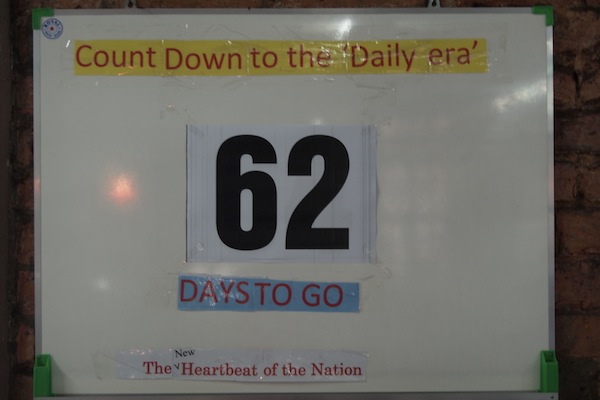

For the last 50 years, Myanmar’s journalists have fled to the Thai and Indian borders, where they provided some of the only insights available to anyone — Burmese inside the country and outside observers alike — into the brutal actions of their government. Some were driven outward in patterns flowing from their ethnic belongings: the Kachin, Shan, and Karen went east and southeast into Thailand. Supporters of the pro-democracy movement fled to Thailand or Europe, where they sent radio and TV signals and print media back home to Burma. The casual observer of the Myanmar of today can almost be forgiven for failing to notice that past. Following two heralded reform elections and a two-year period of economic opening, today Yangon sprawls with development projects and capitalistic fervor amid its decaying British-colonial buildings. Busy consultants advise Fortune 500 clients about a “greenfield” country, with over 90 percent of its 60 million people lacking mobile phones, Internet service, or bank accounts. That same tide of growth sweeping the country is affecting the media business just as much as everyone else. Those in exile find themselves gauging return to the country that hunted them only a few years ago while weighing real business decisions in anticipation of the tens of millions of Burmese expected to be newly-wired with phones with Internet connections by 2015. Existing Burmese private media plan their own expansions. Both are caught in an exaggeration of the U.S. media's situation — needing to firmly keep one foot in the past to survive while aiming forward into a digital frontier that barely even exists yet. Opportunities in print, but with hurdlesConsider Kyaw Zaw Moe, the English editor of The Irrawaddy, one of the most popular Burmese exile media websites. For 10 years, as a result of his involvement in political agitation following protests in 1988, he remained imprisoned in the notorious Insein Prison. When he was released, he fled Myanmar and joined his brother Aung Zaw, The Irrawaddy’s founder, in Thailand. Recently, these are some of the question occupying his thoughts: how to find office space, which has become prohibitively expensive in Yangon; how to find advertisers without connections to a blacklisted individual that could spell ruin for him; how best to interact with his Facebook readership, which is growing at an extremely fast clip; and how to budget for mobile at the same time. This is no longer the Myanmar he knew just a few years ago. But first, his priority is print. "You can make a lot of money out of it," says Kyaw Zaw Moe. Indeed, media companies are preparing for a new moment in Myanmar publishing — the "daily era," as it’s being called. Beginning April 1, newspapers — called "journals" in Myanmar, and until now published weekly in large, bound format — will be able to publish daily under a less stringent censorship regime than ruled in the past. Thaung Su Nyein, the CEO of Information Matrix, which publishes several of Myanmar's highest-circulation weekly journals, said he expects daily circulation to reach that of the weeklies within a year, but that it will take some time for revenue to catch up. He says it could take three years to turn a profit, and other publications quoted similar timeframes. News organizations are also in a struggle to find reporters. An editor at The Myanmar Times, another of the leading publications, explained to me that because Myanmar has lacked a press culture built around storytelling and probing reporting, there’s a lack of available talent.  A countdown on display in the lobby of The Myanmar Times, photographed earlier this year, for its expected launch as a daily publication. Exile publishers trying to come home have additional burdens. Aung Zaw had to eat the full costs of a first edition the Irrawaddy published a few months ago. He does not yet know the specifics about readership and distribution advertisers demand, so for now, the publication is ad-free. On top of that, because nearly every sector of industry has someone connected to someone on an international financial blacklist, a “crony,” those reliant on international donations are in a bind. Aung Zaw hesitates out of concern that if he goes into business with the wrong person, he will lose support from an organization such as the National Endowment for Democracy, an organization funded by the American government that blunt in the past about the strings attached to its support. The Democratic Voice of Burma, a TV and radio broadcaster originally founded with aid from the Norwegian government, is in a similar situation.  Print journals are still found handily at just about any street corner in downtown Yangon. In this way, far from heralding the arrival of "the end of censorship" and a new golden era of Burmese press, the move to daily is but one juncture in a larger set of transitions defining the new state of media in Myanmar. Even with its remarkable turnabout in the last few years, the country is still finding its way. A prime example of that is the limited distribution of the dailies. Truck and bicycle paper routes will be concentrated in Yangon, the most populous city, so much of the vast majority of the country in smaller ethnic enclaves or rural areas will be outside the delivery zones. A second issue are the new media laws: How a "Burmese" legal system will look is still being decided by lawmakers, many of whom are writing bills based on liberal democratic ideals for the first time. A highly criticized, recently drafted media bill contained arbitrary provisions to jail journalists, tied to a new censorship board. Shawn Crispin, southeast Asia representative for the Committee to Protect Journalists, told the AP: “If passed in the current form, the draft law will essentially replace Burma’s old censorship regime with a similarly repressive new one." The rise of mobileThe greater change happening in Myanmar media is not that different from other countries to have undergone political transition. Limited not by unpaved roads or poor Internet infrastructure, mobile is how most people access the Internet, and social media has taken off at a furious pace to become where consumers and media focus their attention. In Yangon and Mandalay, cell phone use has increased dramatically in the last year, and youth and adults for the most part can get online. With the highest weekly circulation numbers less than a few hundred thousand, already Facebook likes exceed subscriptions. Realizing the fact, weekly journals subverted the weekly prohibition by updating their social media pages and websites not just daily but throughout the day. And exile media posted free of the censorship laws. There is no question that daily newspapers will intensify the media as a civic institution But with Myanmar's demographics and poor infrastructure, it will be mobile and the Internet’s mass expansion — with penetration rates expected to increase 900 percent in the next two years to 80 percent of the population— that will create the most dramatic changes, as suddenly millions of ethnic and disenfranchised groups outside the major cities will more readily coordinate and communicate their concerns with the cities. The development of a diverse and all-inclusive online ecosystem, only budding now in Myanmar, is seen as the point when the new media laws will be tested hardest. And already, media companies are preparing. Organizations say they have a few ideas ready to go to court new mobile users, like an SMS-based news system and expansion to an existing dial-in news service. With the call service, you dial a number to hear a short series of the day’s news recordings — almost like radio. Services such as these are seen as ways to attract readers, rural or urban, who may be outside print distribution or want to be on a different pricing plan. Another system many mentioned wanting to eventually have is a way to aggregate text messages to create some kind of interactivity with the audience. “We need to not just have one-way connection,” says Aye Chan Naing, editor-in-chief of the Democratic Voice of Burma. One way organizations may create those channels is by partnering with handset makers. In January, after HTC launched the first smartphone with native Burmese-language support, exile media companies sought the company out for a partnership. They’ve also approached Huawei and Samsung. The idea is to make it so that new phones come arrive pre-installed with a “reader” service to access their news and interact with their social media presences. The difference between such a system and Myanmar media today could not be more vast. Exile media operate cross-border, and text messaging is quite expensive. Apps are still a subject of debate: “We would never do something like an app,” says the Irrawaddy’s Kyaw Zaw Moe, pointing to the fact that the Google Play store is blocked and iOS 6 does not have native Burmese-language support, rendering it an inhospitable development environment. But those I have spoken to inside Google say that change to that system is on the way. [Update: Unblocked as of today.] And even so, other publications stressed that apps are absolutely on the horizon. But for quite some time, the small rebellions by Burmese media to adapt to the cracks in the government’s information blockade will continue to be paramount. A part of the Burmese press's history, strategic experimentation has roots in exile media, which tested different paper sizes and print layouts to enable a quick paper fold during a search. The Democratic Voice of Burma has turned Gchat into an anonymous source-cultivation tool. By putting up a status message and asking for a source in a particular region or with an area of expertise, newsgathering can start within a few minutes. It posted its email address to its site and encouraged listeners to add it to their chat contacts. DVOB now has 22,000 chatters in its rolls. (This has been complicated lately as a result of the hacking of Burmese journalists’ Gmail accounts, but an editor I spoke to at Mizzima, another of the largest of the exile media organizations, said he had reason to suspect the hacking he experienced may be from a different government.) Trends for Facebook are particularly impressive. The Myanmar Times receives has over 73,000 likes on its Facebook page despite receiving only 12,000 unique visitors to its website per month. Facebook is also used by ministry leaders, who gather subscribers and browse news story threads to see instant feedback from the citizenry into reforms. A last issue is that while expansion is certainly on the minds of exile and domestic groups alike, just as much — if not even more so — is the fact that the Myanmar media environment is extremely competitive and clubby. A number of "cronies" with verticalized business monopolies and deep connections in government run media businesses. The competition is certain to be fierce, and some say the current environment, in which dozens of print journals exist, may whittle down to four or five in a few years as readership consolidates. Just in my short time visiting The Myanmar Times, one of the more independent publications, I witnessed an ownership fight within the newsroom that escalated into a physical confrontation and 30-minutes of door-slamming and shouting. I was told that if I took photos, I would likely be escorted from the building. A few days later, I learned six charges had been filed. The dispute stemmed from complications from one editor's politicized imprisonment several years ago, as well as earlier media laws. It’s impossible not to be overwhelmed in Yangon, though, by whatever you experience. At any moment, not far from wherever you stand, rebels fighters seeking territorial independence clash with the military, international telco executives court ministries, and exile media groups guide the process towards a new media law. All anyone knows now is one way or another, Myanmar’s next story will come from whatever results. Top photo of monk reading newspaper by Chris Beckett used under a Creative Commons license. Other photos by Sam Petulla. |

| Posted: 22 Mar 2013 10:13 AM PDT

NEW YORK — New York University’s hyperlocal East Village blog has found a new home and a new name. After a two-and-a-half-year partnership with The New York Times, the newspaper is shutting down The Local: East Village and NYU is launching a similar collaboration with New York magazine. Coming later this spring: Bedford + Bowery, a blog that will expand its focus to include the East Village, the Lower East Side, and neighborhoods of Brooklyn (Williamsburg, Greenpoint, and Bushwick). “The Times decided it didn’t want to do these locals anymore and told us a while ago that they were going to withdraw from our arrangement, which they of course have a total right to do,” NYU professor Jay Rosen, who helped launch the blog in 2010, told me. “And we had to ask ourselves if we wanted to publish it ourselves, or declare victory and fold, or look for another partner.” New York magazine is a good fit, he says, for a couple of reasons. Bedford + Bowery will be able to expand the breadth of its coverage at the magazine, with more of an emphasis on culture. “New York magazine is a little more focused on the creative class, if you want to put it that way, as Richard Florida says,” Rosen said. “It is a good fit and a large portion of our grad program is people interesting in magazine journalism — or what used to be called magazine journalism.” It was the students who pushed for an expansion to Brooklyn, where many of them live, NYU’s Local East Village editor Daniel Maurer told me. (Maurer has a history with New York, where he co-founded its Grub Street blog before joining NYU.) “They made a convincing argument that these neighborhoods represent a community of interest — a shared set of characteristics and concerns,” Maurer wrote in an email. But at a time when “hyperlocal” is a buzzword that’s lost some of its buzz — you don’t see this kind of headline as often anymore — the decision to broaden coverage may also be a way to tweak the model. “We’ll still be covering street-level stories that wouldn’t be reported otherwise but, in the New York magazine tradition, we’ll also be taking more of a big-picture look at trends and tectonic shifts across all of these neighborhoods and beyond — something I think students who are concentrating in magazine writing will appreciate,” Maurer wrote. Maurer also notes that the policy of paying students for their contributions — full-time interns and those “who produce significant enterprise” — will continue. From New York magazine’s perspective, the collaboration offers a chance to dive back into block-by-block level local coverage. “Our website has become a little bit more national in the past couple of years,” said Ben Williams, editorial director of nymag.com. The contract between NYU and New York magazine does not have a set term, and the magazine is committed to experimenting with the school for at least a year, he told me. There’s also the possibility that Bedford + Bowery will serve the function of an in-house source of granular news nuggets — the kinds of hidden news gems that bigger publications have long mined small-town papers or individual blogs for — that have the potential of becoming bigger stories. In other words, the value of a hyperlocal approach isn’t on the revenue side but on the editorial side: “A feeder is a good way to look at it, definitely,” Williams said. So what does all of this tell us about The New York Times’ priorities? (I caught up with Jim Schachter, then an associate managing editor for the Times, last summer when Capital New York reported the Times’ plans to shutter The Local: East Village.) In short, not a whole lot that we didn’t already know. “I think for the Times, it’s pretty simple,” Rosen said. “They are paring their operations down to things that they think are essential services — and it’s of a piece with selling The Boston Globe — where they have one or two things that they’re going to do, which is they’re The New York Times and they’re global and that’s it. Everything else is being either done away with or downsized.” As Schachter put it last year, The Local was a way for the Times to explore how to “prompt communities into the act of covering themselves in a meaningful way,” a worthy goal that ultimately wasn’t practical to keep pursuing. And while working with The New York Times was a great opportunity for students, it wasn’t always ideal for them to have to operate within the framework of such a huge organization. Again, Rosen: “Because we won’t be inside the Times’ back end, which runs like 100-plus blogs, and we won’t have to go through their developer department to change sutff, we hope to have a little more agility with the site and be able perhaps to do things that maybe wouldn’t be right for the NYT because it has to move so slowly.” With agility, NYU hopes, will come more room for experimentation. The idea is to make Bedford + Bowery more of a laboratory than a simple content factory. Students won’t just file copy, photos, and videos. They’ll also try to build something that New York magazine can use. “Journalism schools, for so long, they just tried to produce workers who could be plugged into a production team tomorrow,” Rosen said. “Now they have to contribute a little more than that.” Image courtesy the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute. |

| This Week in Review: British papers fight new regulations, and Pew’s (mostly) dire look at news Posted: 22 Mar 2013 07:30 AM PDT

British press rails against regulations: Much of the British press is livid this week over new government regulations that would establish a tougher independent regulator that could order corrections and fines for wrongdoing. The regulations came out of the Leveson Inquiry report released last year in response to the News Corp. phone hacking scandal, and they are to be inscribed in a royal charter, which is more difficult to change than standard statute. The BBC and New York Times have overviews of the regulations, and The Guardian has some more particulars. The press was outraged. The Guardian and New York Times reported on their objections, which centered on the regulations’ enshrined limits on their freedom into statute and the increased power of the new regulatory body. As The Guardian noted, various newspaper groups are contemplating legal challenges to the new regulations, and even forming several breakaway regulatory bodies. There were several columns outlining newspapers’ objections: The New Statesman’s editorial board, The Economist, The Spectator’s Fraser Nelson, The Telegraph’s Boris Johnson (also known as the mayor of London), and The Guardian’s Simon Jenkins all voiced their disapproval, and The New York Times chimed in from across the Atlantic. Said Johnson, “If Parliament agrees to anything remotely approaching legislation, it will be handing politicians the tools they need to begin the job of cowing and even silencing the press.” There was some pushback to the press’ howling, too. British filmmaker and politician Lord David Putnam said the press is stuck in an antiquated mindset in which it has “the right of kings.” The New Statesman’s Alex Andreou argued that the British press has failed in its chances at self-regulation, and Kevin Anderson said their objections aren’t about freedom of the press, but freedom from accountability. Another group was also alarmed at the new press regulations — bloggers. The Guardian’s Lisa O’Carroll wrote that bloggers are likely covered by the regulation and could face larger “exemplary” fines, just like the newspapers, if they don’t voluntarily sign up to be subject to the regulator. Cory Doctorow of BoingBoing argued that the deal’s language is vague enough that it could include anyone who uses Twitter and Facebook, too. At The Guardian, Emily Bell said the regulations are operating from a web-illiterate perspective that still sees a coherent “press” and “public.”

A pessimistic picture of news: The Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism released its annual State of the News Media report this week — as usual, a comprehensive, insightful, and data-filled look at where the industry is today. You can drill deeper into it with the Lab’s podcast with PEJ acting director Amy Mitchell. The report covers a broad range of topics, from social news consumption to campaign coverage to network, cable, and local TV to alternative media. In such a wide-ranging report, there’s plenty of data to support both optimism and pessimism about the future of news. Mathew Ingram of paidContent offered a few tidbits on both sides of the glass-half-empty/glass-half-full divide. The central narrative around the study, though, was decidedly negative: Years of cutbacks in resources within the news industry are bearing distasteful fruit in the form of lower-quality coverage and diminishing audiences. Poynter’s Andrew Beaujon has a good summary of the situation, and as Mashable’s Lauren Indvik emphasized, the news industry’s cuts are corresponding with a rise of various ways for organizations to circumvent the media to reach the public themselves. The New York Times focused on the effects of this shrinking in local TV news, and Poynter’s Rick Edmonds looked at the grim picture for newspapers. The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson highlighted the discrepancy between print and digital ad revenues as “the scariest statistic about the newspaper business today.” Slate’s Matthew Yglesias took issue with all this hand-wringing, arguing that from the consumer’s perspective, things are actually fantastic — there’s never been more good, easy-to-access information. Several people countered this assertion: Media analyst Alan Mutter countered that Yglesias is mistaking quantity for quality, The Atlantic’s Conor Friedersdorf said the picture is much bleaker on the local level, and Daily Download’s Ben Jacobs that just because people have access to all this information doesn’t mean they’re consuming it. Others saw an important niche for digital tools in Poynter’s report: Amy Gahran of the Knight Digital Media Center highlighted the crucial role of mobile media for community journalism, and j-prof Alfred Hermida pointed out the indispensability of social media for journalists. Another point that drew attention was Pew’s finding that opinion is taking up a greater share of cable news programming, with MSNBC carrying the most opinion and CNN showing the most change since 2007. The Washington Post’s Erik Wemple noted the profitability of cable-news opinionating, and Mediaite’s Joe Concha urged MSNBC to own its opinion-heavy identity.

Slate’s Chris Kirk and Heather Brady cleverly noted that Reader is very, very far from the first service Google has killed, and management prof Joshua Gans wondered whether Google Scholar might be next. Developer Clay Allsopp differentiated between Reader as a product and Reader as a symbol, saying that the former was clunky and antiquated, while the latter was a bulwark against the “walled garden” approach. Several more writers made the popular case for Reader as a warning against using free, corporately owned tools. The Observer’s John Naughton pointed to that as a lesson of Reader’s downfall, and Instapaper’s Marco Arment and programmer Christoph Nahr both argued that free pricing works in the short run but has damaging long-term implications. What Google did with Reader, Arment wrote, was effectively predatory pricing, which turned what could have been a thriving industry into a “proprietary monoculture.” Jack Shafer of Reuters said this isn’t Google’s fault; you just get what you pay for, and its free service was more of a gift while it lasted.

The Washington Post’s paywall: The Washington Post, the most prominent American newspaper still holding out against an online pay model, announced this week it would join the ranks of the paywalled with plans to institute a metered model this summer. (The mantle of most prominent American holdout now passes to USA Today.) The plan is quite modest, though — users will get 20 free page views per month, and students, educators, government employees, and the military will all get free access. As Jeff Bercovici of Forbes noted, those loopholes will encompass a significant percentage of DC-area residents. Ryan Chittum of the Columbia Journalism Review gave some “better late than never” approval to the paywall, but criticized the large loopholes as poor design: “They largely won't pay to read at home what they get at work for free—which is where most reading is done anyway.” Reading roundup: Plenty of other smaller stories to check out during this busy week: — The Washington Examiner, the free daily newspaper owned by Philip Anschutz, announced that it will cease daily publication in June and laid off 87 employees, according to the Washington City Paper, though 20 new positions will be hired. The locally oriented paper will turn into a weekly magazine and website focused instead on national politics, aiming for straight news reporting supplemented with conservative opinion. The Washington Post’s Erik Wemple gave more details on that plan and compared it to Anschutz’s other political publication, The Weekly Standard. — Some follow-ups on the arrest last week of Reuters social media editor Matthew Keys for helping Anonymous attack news sites in 2010: Keys’ attorney said he was actually doing undercover journalism on Anonymous. Gawker’s Adrian Chen gave some more details on that defense, as well as Keys’ Internet past. Keys’ former co-worker, Judy Farah, reflected on Keys as a friend, and Gerry Smith of the Huffington Post used the case as an example of the security dangers of rogue employees, while the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Hanni Fakhoury used the case to look at problems with sentencing under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. Caitlin Dewey of The Washington Post, meanwhile, countered the idea that Keys is comparable to Aaron Swartz. — A few leftover pieces from the closing of the alternative weekly the Boston Phoenix late last week: The Phoenix’s Carly Carioli and the Columbia Journalism Review’s Justin Peters gave elegies for the paper, and the Lab’s Joshua Benton pointed to its demise as a reminder that a switch from newsprint to glossy print doesn’t solve the basic problems alt weeklies are facing. Jack Shafer of Reuters zoomed out to explain why alt weeklies everywhere have been declining for years, and Poynter’s Andrew Beaujon pointed out their declining circulation in Pew’s State of the Media report. — For those interested in media research or analytics, two extremely helpful posts this week: First, at the Lab, Matt Stempeck of the MIT Center for Civic Media released a script for tracking mentions of words, phrases, or people in the recently released TVNews Archive. Second, New York Times OpenNews fellow Brian Abelson demonstrated a metric for engagement on news apps. — Finally, the post just about everyone currently or formerly in newspapers seemed to be passing around this week was this essay by former newspaper reporter Allyson Bird about why she left the business. It’s a thought-provoking perspective on what it’s like to work in newspapers right now. |

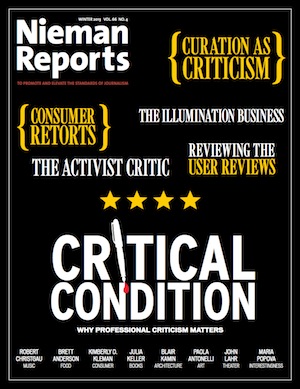

| From Nieman Reports: When going undercover, an ethics of utility versus an ethics of rules Posted: 22 Mar 2013 07:00 AM PDT Editor’s note: Our colleagues at our sister publication Nieman Reports are out with their new issue, and there’s a lot of great stuff in there for any journalist to check out. Over the next few days, we’ll share excerpts from a few of the stories that we think would be of most interest to Nieman Lab readers. Be sure to check out the entire issue. Here, journalism legend Philip Meyer looks at the ethics (and efficacy) of undercover reporting.

Now that cell phones can make movies, and the Internet gives access to a mass audience to everyone with a computer, undercover reporting can be done by anyone. But so far, at least, it seems most likely to be done by political activists — including those with intent to mislead. Jones’s self-published They’re Gonna Murder You: War Stories From My Life at the News Front reminds us of the need to find a way to create and maintain institutions that will use those tools responsibly and fairly. Born in Jacksonville, Florida in 1934, he put his writing skill and mechanical ingenuity to work in the service of his journalism. His early career with his hometown paper reminds us that newspapers were a natural monopoly in most places, and bad ones could flourish as easily as good ones. A railroad company tied to the city’s power structure owned both Jacksonville papers and they often blocked controversial projects. Jones sought to escape by applying simultaneously to the Nieman Foundation and The Miami Herald. Both said “yes.” He went to Harvard first, joining the Nieman class of 1964. Jones and I had overlapping service with the Herald and its parent company at the time, Knight Newspapers. He faithfully captures the paper’s culture, and in the chapter, “Bosses with Balls,” pays tribute to two strong creators of that culture, publisher John S. Knight and editor John McMullan. They were tough newsmen who recruited good reporters and then backed them up. Keep reading at Nieman Reports » |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

The story of legendary undercover reporter Clarence Jones does more than fill me with nostalgia for the rough-and-ready days of newspaper and broadcast reporting. It makes me want to imagine the new forms of mass media that could enable such public-spirited derring-do to flourish again.

The story of legendary undercover reporter Clarence Jones does more than fill me with nostalgia for the rough-and-ready days of newspaper and broadcast reporting. It makes me want to imagine the new forms of mass media that could enable such public-spirited derring-do to flourish again.