Nieman Journalism Lab |

| BuzzFeed with a press pass: What happens when the GIF kings try to take Washington? Posted: 21 Aug 2012 08:30 AM PDT

WASHINGTON — You should know going in that this is a story about BuzzFeed that BuzzFeed would never run. This story is longer than the last 10 articles out of the new BuzzFeed Washington, D.C. bureau combined. Some recent examples:

That last one about Kristol stands out as long, but it’s still a slender 515 words, including a 189-word blockquote excerpting from the Politico story that prompted BuzzFeed’s. But counting words is a silly way to assess BuzzFeed content because BuzzFeed doesn’t implicitly value length. “I’ve written stories that are several thousand words,” said John Stanton, who heads up BuzzFeed’s new Washington bureau, which opened in July and is the closest thing to a physical manifestation of the site’s expansionist plans. “I’ve also written stories that are 300 words. If something doesn’t deserve more than 300 words, you can just write it. You don’t have to backfill it.” “A lot of our stories are 400 words or 500 words,” reporter Zeke Miller told me. “A concise hit. We’ll boil it down to a question you have, and here’s the answer. Some of my favorites are things that seem so obvious. Often just the act of doing that brands it as conventional wisdom, but it’s not actually until you say it.”

That BuzzFeed vision of reducing content to its most atomic, most snackable unit has worked brilliantly for celebrities, listicles, and cats — quirky hats and real-life angry birds. But just as the rest of the news Internet is getting more BuzzFeedy — cf. the suddenly everywhere animated GIF — BuzzFeed is concretizing its move into politics with an actual D.C. operation. That actual operation doesn’t include an actual office: The three-person team works mostly out of the Senate Press Gallery in the U.S. Capitol. (Right now, only Stanton and Chris Geidner are full-time in Washington. Campaign reporter Miller will join them to cover the White House in November, and Stanton is in the process of hiring a fourth reporter.) But office or no office, Washington’s clubby press corps is paying attention. BuzzFeed’s best pieces are something like exceptional standup comedy in that they articulate something you feel like you already knew but weren’t totally aware of. That’s what makes the site resonate as authentic, and authenticity goes a long way in the chaotic rush hour of information that is the Internet age. “The reason that people pay money to read publications, the reason that people come to your publication, is that you are a trusted voice,” Stanton said. “You should be able to call a spade a spade. You should be able to say, ‘This is silly.’” For BuzzFeed, being a trusted voice is about sharing things with readers in the same ways that readers share with one another. First there’s the tone component: “We did this story about an abortion vote, the D.C. abortion bill,” Stanton said. “Well, the bill was never going to go anywhere. It wasn’t even going to pass the House. And they knew it wasn’t going to pass the House. It’s just this kabuki theater. And so we wrote the lede saying this was probably the most blatant example of kabuki theater all year, which it was, and for the art, we used an image of kabuki dancers. Roll Call would never do that. It’s sort of a fun way to tell people this is just a bunch of crap that’s going on, and it’s a political vote, and if you believe in it or not, don’t think it’s going to happen because it’s just to pander to both sides.” Then there’s structure. The value of smart analysis notwithstanding, why write a long narrative describing a video clip in words when we have the technology to publish and share video in a matter of seconds? Forward a video clip to a friend, and you might just paste the link in the body of an email with a brief message in the subject line. So, for example, if the video you wanted to share was about a campaign promise the president didn’t keep, maybe that subject line would be: “Democrats prepare to attack Paul Ryan for his proposal to overhaul Medicare for those 55 and under, but lack a clear plan themselves.” Boom. You just wrote a BuzzFeed article. If the best way to tell a finance story is through GIFs, then that’s what you should do. But BuzzFeed Editor Ben Smith wants you to know that the Washington bureau will be doing the hard work of journalism, even if it’s packaged in a new wrapper: “We’re going to break news, and tell stories in a really compelling way. There’s no trick.”

If there is a trick, it’s in breaking down the divide between the light and the serious. “It’s the whole thing of the cats versus hard news,” Stanton said. “Who cares? Put it on the front page. If it’s news, it’s news. If it’s interesting, it’s interesting.” The shareable quick hits are a vivid part of BuzzFeed’s DNA. But what Smith means when he says the site doesn’t have any tricks is that its D.C. bureau will be run with boots-on-the-ground tenacity. The constant flow of new content to the overall site means that there’s less pressure on the political reporters to file for the sake of filing. Paradoxically, because there are only four reporters in the bureau, BuzzFeed has the luxury of being selective. If there’s no way you can do every story, you get to be choosier overall. But ultimately, it’s all “very traditional,” Stanton insists. “I go to press conferences and hang around in hallways,” he said. “How I’m approaching the job, it hasn’t changed. Stalk people, harass people. The only thing that’s different is there’s not this — because we have so much content on our site — there’s no need for us to feed the beast. Little micro-movement stories, we don’t have to write. That frees me up a lot.” BuzzFeed prizes speed, smart analysis, and a willingness to burst the beltway bubble and plainly tell readers what something means or why it matters. Geidner, a lawyer who joined BuzzFeed’s D.C. bureau after a stint covering Congress for the LGBT newsmagazine Metro Weekly, will contribute stories to both the politics vertical and a new LGBT vertical (a move that D.C. bureau staffers unanimously consider “brilliant”). “When Ben [Smith] approached me about possibly coming to BuzzFeed, he said, ‘Since I was at Politico, I didn’t really understand why this wasn’t being taken seriously as a stand-alone beat. The biggest places were sort of like — the legal stories were with the courts reporter, the politics stories were with the politics reporter, the defense stories were with the defense reporter — and you sort of lost the cohesive sense of what this means in the bigger picture,” Geidner said. “I think that failure is sort of why there are all these stories of ‘When did this happen? Gay rights is now normal,’ and it’s like maybe if you’d been covering it as a cohesive unit, you would have seen it.” BuzzFeed’s D.C. contingency also aims to disrupt White House coverage, which Stanton says Miller will cover infiltraton-style, as an outsider coming in. (Though he’s at the beginning of his journalism career, it’s somewhat of a stretch to characterize Miller as an outsider: He’s been on the presidential campaign trail since he started at BuzzFeed in January.) “I want to see if Zeke can — and I think he can — crack the White House,” Stanton said. “It’s like getting blood from a stone to get them to comment on something that should be easy to comment on. Like, is it Tuesday? ‘Well, off the record, I can’t tell you.’” For his part, Miller says he plans to be at the White House as much as he can. Again, boots on the ground. But wanting to change the Brady Room institution is much different than actually doing it, and how to make it happen is something that Stanton and Miller say BuzzFeed will figure out as it goes. At the bureau’s launch party in a U Street bar, things were getting meta. Four chandeliers made out of antlers! Edible BuzzFeed LOL/OMG/Win/Fail tags! Tweeting about tweeting about tweeting! Among the few men wearing suits were a couple of guys from C-SPAN, camera crew in tow. They were mock-sheepish about being “the oldest guys here,” but they were also giddy about BuzzFeed. The two organizations are kindred spirits of sorts. Both launched from outside of the media establishment, and got attention for busting out of its traditional format.

“The myth of the news is that people are stupid,” Stanton said. “Editors and publishers have been saying this for years: The public is too stupid to understand hard news. To the extent that that’s true, it’s our fault. People say, ‘Okay, fine,’ and ‘they’re only interested in a Kardashian posterior.’ But people aren’t stupid. I think we need to show people that it’s up to us to write it in a way that has the context, has a compelling narrative to it. If you give them more of this and mix it in with fluff, and it’s treated equally by the publication, the public will start to treat it the same way too.” To the people who get what BuzzFeed is trying to do, all of this seems obvious. But the site isn’t the easiest sell in the traditional media world. Jim Roberts, an assistant managing editor with The New York Times who made a trip to Washington for the party, says orchestrating a partnership with BuzzFeed — they’ll produce video together at the conventions — took months of cajoling within the Times. “Our partnership is something I wanted,” he said. “I engineered it. I said, ‘This is something we need to do.’ I had to convince a lot of really skeptical people. It just wasn’t the easiest thing for everyone to accept.” Stanton says the industry reaction to BuzzFeed in Washington has been welcoming thus far. Along with the Times and C-SPAN, partygoers included folks from Politico, Slate, The New Republic, Roll Call, HuffPo, and so on. Stanton says people have razzed him a little bit about the unusual mix of content on the site — and reaction to BuzzFeed’s rapid ascent calls to mind some of the conversations that took place in the early 1980s, when a colorful, graphic-rich newspaper called USA Today debuted. Stanton: “You know, when Ben came over [to BuzzFeed], I think the entire industry was like, ‘What!?’ But the campaign coverage has become something that all the other reporters read. Sources here who have been paying attention to the campaign or have been somehow involved, they were like, ‘Oh yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah, go work for BuzzFeed. It’s a legit shop.’” In coming months, BuzzFeed’s Washington team will work to build upon that reputation. For a group of reporters that is looking about as far into the future as the presidential debates, thinking about what they’ll be saying about BuzzFeed a year from now seems borderline impossible. “It will be like, ‘The New York Times folding into a subsection of BuzzFeed was amazing,’” Stanton jokes. “No, I want to be able to just say that I don’t think we have screwed up and we have done our readers a service, and not a disservice, and we have not fallen into the traps of either getting too wonky down in the weeds where nobody cares or becoming so sensational that nobody trusts you. Hit them with the news but don’t hit them with any unnecessary force. You see it in a ton of publications these days. Hell, you see it in the little wars that publications have with one another. I don’t understand any of that, the catfights between publications.” Miller, too, says he’s uninterested in neatly drawn rivalries with other publications. “It’s not that we’re peerless, it’s that we have this massive universe of peers. I want to beat all of them on everything. Maybe it’s BuzzFeed versus the Internet. Every day is us being as good as we can possibly be that day. You’re going to BuzzFeed because you want to be entertained, you want to be informed. And we will give you all of the things you are looking for. I’m competing against the Internet, so anybody on the Internet — which is just about everybody at this point — is my competition. And the Internet’s a big place.” Oh yeah, sorry for all the words. Here’s a GIF that BuzzFeed thinks might be the greatest in the history of the Internet (I agree):

Image derived from photo by TexasGOPvote.com used under a Creative Commons license. |

| Inside the Star Chamber: How PolitiFact tries to find truth in a world of make-believe Posted: 21 Aug 2012 07:30 AM PDT

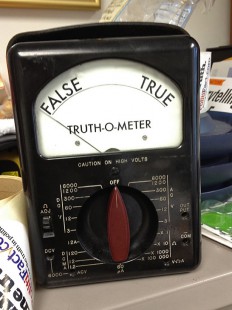

WASHINGTON — PolitiFact’s “Star Chamber” is like Air Force One: It’s not an actual room, just the name of wherever Bill Adair happens to be sitting when it’s time to break out the Truth-O-Meter and pass judgment on the words of politicians. Today it’s his office. Three judges preside, usually the same three: Adair, Washington bureau chief of the Tampa Bay (née St. Petersburg) Times; Angie Drobnic Holan, his deputy; and Amy Hollyfield, his boss. For this ruling — one of four I witnessed over two days last month — Holan and Hollyfield are on the phone. Staff writer Louis Jacobson is sitting in. He is recommending a rating of False for this claim, from Rep. Jeff Duncan (R-S.C.), but Hollyfield wants to at least consider something stronger:

This scene has played out 6,000 times before, but not in public view. Like the original Court of Star Chamber, PolitiFact’s Truth-O-Meter rulings have always been secret. The Star Chamber was a symbol of Tudor power, a 15th-century invention of Henry VII to try people he didn’t much care for. While the history is fuzzy, Wikipedia’s synopsis fits the chamber’s present-day reputation: “Court sessions were held in secret, with no indictments, no right of appeal, no juries, and no witnesses.” PolitiFact turns five on Wednesday. Adair founded the site to cover the 2008 election, but the inspiration came one cycle earlier, when a turncoat Democrat named Zell Miller told tens of thousands of Republicans that Sen. John Kerry had voted to weaken the U.S. military. “Miller was really distorting his record,” Adair says, “and yet I didn't do anything about it.” The team won a Pulitzer Prize for the election coverage. The site’s basic idea — rate the veracity of political statements on a six-point scale — has modernized and mainstreamed the old art of fact-checking. The PolitiFact national team just hired its fourth full-time fact checker, and 36 journalists work for PolitiFact’s 11 licensed state sites. This week PolitiFact launches its second, free mobile app for iPhone and Android, “Settle It!,” which provides a clever keyword-based interface to help resolve arguments at the dinner table. (PolitiFact’s original mobile app, at $1.99, has sold more than 24,000 copies.) The site attracts about 100,000 pageviews per day, Adair told me, and that number will certainly rise as the election draws closer and politicians get weirder.

If your job is to call people liars, and you’re on a roll doing it, you can expect a steady barrage of criticism. PolitiFact has been under fire practically as long as it has existed, but things intensified earlier this year, when Rachel Maddow criticized PolitiFact for, in her view, botching a series of rulings. In public, Adair responded cooly: “We don’t expect our readers to agree with every ruling we make,” is his refrain. In private, it struck a nerve. “I think the criticism in January and February, added to some of the criticism we've gotten from conservatives over the months, persuaded us that we needed to make some improvements in our process,” Adair told me. “We directed our reporters to slow down and not try to rush fact-checks. We directed all of our reporters and editors to make sure that [they're] clear in the ruling statement.” Adair made a series of small changes to tighten up the journalism. And for the first time he invited a reporter — me — to watch the truth sausage get made. The paradox of fact-checkingTo understand fact-checking is to accept a paradox: “Words matter,” as PolitiFact’s core principles go, and “context matters.” Consider this incident recently all over the news: Harry Reid says some guy told him Mitt Romney didn’t pay taxes for 10 years. It’s probably true. Some guy probably did say that to Harry Reid. But we can’t know for sure. To evaluate that statement is almost impossible without cooperative witnesses to the conversation. Now, is Reid’s implication true? We can’t know that, either, not until someone produces evidence. So how does a fact checker handle this claim? The Truth-O-Meter gave Reid its harshest ruling, “Pants on Fire,” a PolitiFact trademark reserved for claims it considers not only false but absurd. In the Star Chamber, judges ruled that Reid had no evidence to back up his claim. “It is now possible to get called a liar by PolitiFact for saying something true,” complained James Poniewozik and others. But True certainly would not have sufficed, here not even Half True. Maybe the Truth-O-Meter needs an “Unsubstantiated” rating. They considered it, but decided against it, Adair told me, “because of fears that we’d end up rating many, many things ‘unsubstantiated.’” Whereas truth is complicated, elastic, subjective… the Truth-O-Meter is simple, fixed, unambiguous. In a way, this overly simplistic device embodies the problem PolitiFact is trying to solve. “The fundamental irony is that the same technological changes and changes in the media system that make organizations like PolitiFact and FactCheck.org possible also make their work less effective, in that we do have this highly fragmented media environment,” said Lucas Graves, who recently defended his dissertation on fact-checking at Columbia University. So the Truth-O-Meter is the ultimate webby invention: bite-sized, viral-ready. Whether that Pants on Fire for Reid was warranted or not, 4,300 shares on Facebook is pretty good. PolitiFact is not the only fact checker in town, but the Truth-O-Meter is everywhere; the same simplicity in its rating system that opens it to so much criticism also helps it spread, tweet by tweet. “PolitiFact exists to be cited. It exists to be quoted,” Graves said. “Every Truth-O-Meter piece packages really easily and neatly into a five-minute broadcast segment for CNN or for MSNBC.” (In fact, Adair told me, he has appeared on CNN alone at least 300 times.) Stories get “chambered,” in PolitiFact parlance, 10-15 times a week. Adair begins by reading the ruling statement — that is, the precise phrase or claim being evaluated — aloud. Then — and this is new, post-criticism — Adair asks four questions, highlighted in bold. (“Sounds like something from Passover, but the four questions really helps get us focused,” he says.)

After briefly considering Pants on Fire, they agree on False. Another change in the last year has created a lot of grief for PoitiFact: Fact checkers now lean more heavily on context when politicians appear to take credit or give blame. Which brings us to Rachel Maddow’s complaint. In his 2012 State of the Union address, President Obama said:

PolitiFact rated that Half True, saying an executive can only take so much credit for job creation. But did he take credit? Would the claim have been 100 percent true if not for the speaker? Under criticism, PolitiFact revised the ruling up to Mostly True. Maddow was not satisfied:

Maddow (in addition to many, many liberals) was already mad about PolitiFact’s pick for 2011 Lie of the Year, that Republicans had voted, through the Ryan budget, to end Medicare. Of course, her criticism then was that PolitiFact was too literal. “Forget about right or wrong,” Graves said. “There’s no right answer if you define ‘right’ as coming up with a ruling that everybody will agree with, especially when it comes to the question of interpreting things literally or taking an account out of context.” Damned if they do, damned if they don’t. Graves, who identifies himself as falling “pretty left” on the spectrum, has observed PolitiFact twice: for a week last year and again for a three-day training session with one of PolitiFact’s state sites. “One of the things that comes through clearest when you spend time with fact checkers…is that they have a very healthy sense that these are imperfect judgments that they’re making, but at the same time they’re going to strive to do them as fairly as possible. It’s a human endeavor. And like all human endeavors, it’s not infallible.”

The truth is that fact-checking, and fact checkers, are kinda boring. What I witnessed was fair and fastidious; methodical, not mercurial. (That includes the other three (uneventful) rulings I watched.) I could uncover no evidence of PolitiFact’s evil scheme to slander either Republicans or Democrats. Adair says he’s a registered independent. He won't tell me which candidate he voted for last election, and he protects his staff members’ privacy in the voting booth. In Virginia, where he lives, Adair abstains from open primary elections. Revealing his own politics would “suggest a bias that I don't think is there,” Adair says. "In a hyper-partisan world, that information would get distorted, and it would obscure the reality, which is that I think political journalists do a good job of leaving their personal beliefs at home and doing impartial journalism," he says. Does all of this effort make a dent in the net truth of the universe? Is moving from he-said-she-said to some form of judgment, simplified as it may be, “working?” Last month, David Brooks wrote:

“I don’t think we were naive. I’ve always said anyone who imagines we can change the behavior of candidates is bound to be disappointed,” said Brooks Jackson, director of FactCheck.org. He was a pioneer of modern political fact-checking for CNN in the 1990s. “I suspect it is a fact that the junior woodchucks on the campaign staffs have now perversely come to value our criticism as some sort of merit badge, as though lying is a virtue, and a recognized lie is a bigger virtue.” Rarely is there is a high political cost to lying. All the explainers in the world couldn’t completely blunt the impact of the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth’s campaign to denigrate John Kerry’s military service. More recently, in July, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee claimed Chinese prostitution money helped finance the campaign of a Republican Congressman in Ohio. PolitiFact rated it Pants on Fire. That didn’t stop the DCCC from rolling out identical claims in Wisconsin and Tennessee. The DCCC eventually apologized. But which made more of an impression on voters, the original lie or the eventual apology from an amorphous nationwide organization? Brendan Nyhan, a political science professor at Dartmouth College, has done a lot of research on the effects of fact-checking on the public. As he wrote for CJR:

If the objective of fact-checking is to get politicians to stop lying, then no, fact-checking is not working. “My goal is not to get politicians to stop lying,” is another of Adair’s refrains. “Our goal is…to give people the information they need to make decisions.” Unlike The Washington Post’s Glenn Kessler, who awards Pinocchios for lies, or PolitiFact, which rates claims on a Truth-O-Meter, Jackson’s FactCheck.org doesn’t reduce its findings to a simple measurement. “I think you are telling people we can tell the difference between something that is 45 percent true and 57 percent true — and some negative number,” he said, referring to Pants on Fire. “There isn’t any scientific objective way to measure the degree of mendacity to any particular statement.” “I think it’s fascinating that they chose to call it a Truth-O-Meter instead of a Truth Meter,” Graves said. Truth-O-Meter sounds like a kitchen gadget, or a toy. “That ‘O’ is sort of acknowledging that this is a human endeavor. There’s no such thing as a machine for perfectly and accurately making judgments of truth.” Political cartoon by Chip Bok used with permission. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

Just beyond the entryway, a couple of youngish guys in matching thick-framed glasses peered at the list in the bouncer’s hands. “Ben Smith said I could come to this,” one said. This seemed odd, the temporary air of exclusivity, the cadence of the guy’s voice when he thought he couldn’t get in, which he did. BuzzFeed’s editorial attitude is that everyone’s invited.

Just beyond the entryway, a couple of youngish guys in matching thick-framed glasses peered at the list in the bouncer’s hands. “Ben Smith said I could come to this,” one said. This seemed odd, the temporary air of exclusivity, the cadence of the guy’s voice when he thought he couldn’t get in, which he did. BuzzFeed’s editorial attitude is that everyone’s invited.