Nieman Journalism Lab |

- The New York Times dives into commenting culture

- The rise of mobile has nearly doubled time spent online

- Turn your followers into gold: Beacon won’t be the Netflix of journalism, but it might help you make rent

- The Hub of the Twitterverse: The Boston Globe has built a localized, tweet-powered news aggregator

- Nextgov’s new iPhone app is en Fuego

| The New York Times dives into commenting culture Posted: 23 Sep 2013 11:53 AM PDT The New York Times gave us not one but two stories this weekend that lead with a lamentation over the state of Internet commenting. “The most obnoxious development of the Web, the wild back alleys where people sound their acid yawps,” wrote Michael Erard on Friday. “The most slimy and vitriolic stuff you could imagine, places where people snipe, jeer and behave like a frenzied mob,” said Nick Bilton on Sunday. Erard’s piece provides a history of online commenting, from Marc Andreesen’s dreams of an annotated web to Fray, an early innovator in audience feedback, to Open Diary, one of the first virtual journaling projects. He concludes with a call to arms for annotation:

And on Sunday, Bilton wrote a Bits blog post about the latest moves for Gawker’s Kinja:

|

| The rise of mobile has nearly doubled time spent online Posted: 23 Sep 2013 11:01 AM PDT Jack Loechner at MediaPost has the details: In the short span from February 2010 to February 2013, U.S. Internet use moved from 451 billion minutes to 890 billion minutes. Leading the way: smartphones (from 63 billion to 308 billion) and tablets (roughly zero to 115 billion). Within the news category, 62 percent of online time is still on desktops and laptops, versus 31 percent on smartphones and 7 percent on tablets. The high desktop/laptop number makes sense — an awful lot of online news is consumed by deskbound office workers — but the tablet share has to be disappointing to all the news execs who bet the iPad would revive their business models. Want to see the future for news? Look at the technology news category, where a full 77 percent of online time is on smartphones. |

| Posted: 23 Sep 2013 09:49 AM PDT “The actual number of readers, at this stage, is kind of irrelevant, as long as the writers are like, ‘This is worth it for me.’” Not exactly the wisdom you’d expect from Adrian Sanders, one of three founders of the new journalism site Beacon. (Yeah, at www.beaconreader.com.) The new website, which Sanders cofounded with former Facebook managing editor Dan Fletcher and developer Dmitri Cherniak, is based on the idea that loyal readers will pay to read the writers they like. Specifically, Beacon readers will pay five dollars a month for access to all of the content produced by the writers Fletcher has assembled — with the largest share (about 60% of that money) will go to a single, “favorite” writer, with the remainder to be split among the rest. This is, of course, not the first such experiment that follows the line of Sullivanesque reasoning that a single journalist can build a personal brand that people will pay for. In April, we wrote about Dutch writer subscription experiment Die Nieuwe Pers; it has since been purchased by The Post Online, which continues offering that model to readers, but with the addition of core news which is free. Through Twitter, I also learned of another Dutch experiment called Tone which is structurally even more similar to Beacon — 23 high-profile writers produce current affairs content for a totally open platform, and then share in the “operational result, which means,” its founder Arno Laeven wrote in an email, “the more we sell the more they can earn.” Other projects to which Beacon has been compared include Tugboat Yards, a yet-to-be-launched startup somewhat more narrowly aimed at helping writers with preexisting followers monetize their popularity. “When we first started out, I think the dream was that someone could make rent doing this,” says Sanders. But the plan was never that salaried writers would be leaving their jobs to write for Beacon. Their core team of 28 writers is made up mostly of freelancers who live and work abroad, with bylines from outlets like The New York Times, The Washington Post, the BBC, CNN, Time, Foreign Policy, The Guardian, and more. As seasoned freelancers, they see Beacon as merely one revenue-generating tool in their diversified toolbox. That’s why even though it’s the subscriber base that will determine how much money Beacon makes, for Sanders, it’s the satisfaction of the writers that will determine success or failure. “People are in different situations looking for different things,” says Fletcher. “Some folks are really happy just to have a place to tell the types of stories they can’t tell anywhere else, and that as much of the money is a part of the value proposition. Other people really want to hustle and get to a number of subscribers so they can spend less time pitching other places and more time writing for their most engaged audience.” Beacon does not currently provide editorial support for its writers; the readers are the quality control, Fletcher and Sanders said. As much as possible, they want their writers — already accustomed to a degree of independence — to view Beacon as a platform they can use, not as a publication with any kind of overriding editorial goals. “I don’t think Beacon having a centralized pool of editors makes as much sense,” says Fletcher. “In some of the conversations we’ve had with writers, it’s, ‘I have this editor I really love to work with because they challenge me and they push my work and they know what they’re talking about — is there a way we can bring them on to Beacon and I can work with them and split some of the money back and forth?’ To me, that’s a really interesting idea and eventually we’d like to, I think, explore some stuff like that.” Still, outside of the people that they bring aboard, that gives Beacon’s founders very little control over the content they’re publishing — which could eventually sit uneasily with the site’s central proposition that readers are willing to pay for high-quality journalism. Beacon’s writers do get some structural support. In one of the half-dozen mysterious blog posts that preceded Beacon’s launch, Fletcher writes about the importance of a small but loyal audience — the people who want to pay for your work. “The pitch that I make to writers when we talk to them and tell them about Beacon is, ‘You’re already doing this anyway — why don’t you do it in a way that benefits you directly?’” says Fletcher. Learning how to build, engage, and grow that following — your 1,000 true fans — into something that is profitable for the producer is what Beacon is all about. He sees Beacon as an educational opportunity, to help them understand how to find that loyal audience, and turn them into profit. “What’s interesting to me about launch is, right now we have 28 different people doing 28 different experiments about how they identify their readership,” says Fletcher. “I think we’re going to learn really quickly where these people are.” And it doesn’t hurt, Sanders added, that they have the capacity to build their own technologies — be it in analytics or tools for broadcasting — from the ground up. For a time, De Nieuwe Pers subsidized the early revenue lag for their project by selling some of their software, but Beacon says they currently have no plans to do that. The site itself is clean, simple, and responsive; you can browse writer bios, scan the headlines, and enjoy their work.

At Time, a big part of Fletcher’s job was convincing traditional journalists to make audience building via social media part of their jobs, but at Facebook he realized that social platforms themselves didn’t need journalism’s content to thrive. “Good storytelling can be costly and time-consuming, while status updates and photo uploads are cheap, quick, and plentiful,” he says. “That’s not a knock on Facebook — it just means that I don’t think they’re really focused on ways to sustain important reporting.” Beacon is essentially Fletcher’s attempt to take what Facebook is focused on, targeting an audience, and using it to support journalism. “What we really believe is that writers and journalists and storytellers, the things that they produce, which are the stories, have an inherent value that is worth paying for,” say Sanders. “We think this sort of model — which is kind of a Kickstarter-plus-Netflix for the reader — is a great way to go for that, because you get everything on the platform but you have a direct say in the stories that you want to see.” From the eyes of the consumer, Sanders says, its unreasonable that 10 dollars a month gets you all the music you want from Spotify, 8 dollars a month gets you endless movies and TV from Netflix, but signing on to even a few high quality news outlets — the Times, the Journal, the Post and The New Yorker, say — means paying almost 100 dollars a month: “It’s ridiculous that there’s that big of a disparity.” What’s not totally clear is how Beacon helps mediate that problem. For $5 a month, you get access to a dozen or so stories a week, which is nice, but that obviously doesn’t even scratch the surface of the best journalism out there — even if your favorite writer is on Beacon’s staff, the chances of which are slim. One strength of Beacon’s current model is their willingness to fluctuate and respond as early data comes in. For now, the “referrer” gets around 60 percent of each subscription, but that could change. “Some people are going to have more of a reach right away, and they’re going to bring a larger subscriber base to the platform,” says Sanders. “Other people are going to bring on less, but that doesn’t mean that the work that they provide into the Beacon platform is less valuable. If someone brings in 10,000 subscribers and someone else brings in 100, but the person who produced 100 subscribers writes an amazing piece and everyone reads it on the platform, they should be rewarded for that.” But as Hamish McKenzie wrote for PandoDaily, the greatest challenge Beacon faces will be the sustainability of its business model, as it tries to prove itself as more than a nice way to funnel some money to journalists to something that consumers judge on value: “For longterm success, Beacon needs to host content that people feel they simply must have access to,” he writes. Sanders disagrees, saying the basis of Beacon is far from what we typically think of as crowdfunding. “It’s not, ‘Hey, I’m asking for this money, help me out as a charitable thing.’ It’s like, ‘You value these stories, you value the work that I do, and you’re going to pay for it.’” But with so much content already available — consider the archives of Longform alone — it seems unlikely that many readers will feel they’re missing out without a subscription to Beacon. That doesn’t mean Beacon is doomed — but it might mean that the founders aren’t as close to unraveling the mysteries of the future of journalism as some of their rhetoric suggests. The project is probably most interesting as an experiment around readership; as Fletcher says, they’ll learn a lot from watching this first batch of writers try to grow this very specific type of audience. Still, it’s when they’re at their most modest that their plan seems most viable: “Maybe a freelancer uses Beacon to cover their car payments. I’m from Oregon, so anything about salmon or trees is near and dear to my heart. If there’s a woman who wants to cover that and she’s able to pay her car payment and I get to read that stuff,” says Sanders, “I think that’s a win-win.” |

| The Hub of the Twitterverse: The Boston Globe has built a localized, tweet-powered news aggregator Posted: 23 Sep 2013 08:59 AM PDT

This tweet, in particular, caught fire:

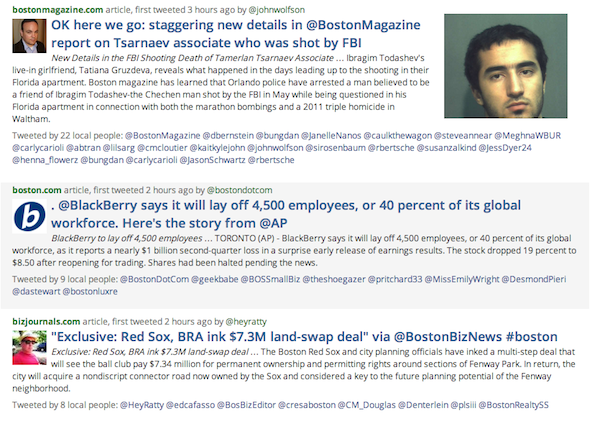

(In fairness, Matt Damon, a napkin, and apples also made that Dunkin newsworthy.) What, exactly, is 61Fresh? And what’s with the name? “Half the people who respond to it ask, ‘What’s up with the name?’ And I say, ‘Oh, it’s like 617, but six-one fresh,” said Chris Marstall, a creative technologist in the Globe Lab. (Out-of-towners: 617 is the primary Boston area code.) The name, like the site, is an experiment. Think of 61Fresh as a close cousin to something like Techmeme, Mediagazer, or our very own heat-seeking Twitter bot, Fuego. Where those algorithmic link aggregators are topic-based, 61Fresh instead has a geographic focus: “It’s philosophically the same,” Marstall says. “It’s using a network to find the most relevant stories in a narrow domain for now.” Every 10 minutes, 61Fresh takes a spin around a localized slice of Twitter searching for rising news items. On any given day, you’re likely to find stories on apartment fires, startup companies, or the Bruins. Unlike some aggregators that mix in some human control, 61Fresh is 100 percent algorithm-driven — which means both that it runs without the need for ongoing staff resources and that the end product can be a little raw, with different versions of the same story repeated during breaking news. The project is still in early stages, and Marstall said they’re still figuring out the best way for users to interact with 61Fresh, which for now exists as a website and Twitter feed. “The stories that pop up are stories drawing interest on Twitter,” he said. “It’s sort of an open question if this can be a standalone site in the future or if this is something that is a compelling part of Boston.com.” But how does 61Fresh figure out what’s news, what’s talk, and what’s noise? The algorithm built by Globe Lab looks for tweets that link to stories or updates from just over 500 pre-selected websites in the Boston area. Aside from recognizable names like Boston.com, and the Boston Herald, the universe also includes stories from radio, TV, town government sites, universities, and blogs, including the growing network of online outlets that cover the particular cross-section of education, technology, and culture unique to the Boston area. “We got three daily newspapers, a bunch of weekly newspapers, we got TV and radio, and all these blogs. That’s just the tip of the iceburg,” Marstall said. “It shows there’s a lot of vibrancy here and a lot of smart people fighting to get attention for their stories.” Here’s how they explain it:

What you get with 61Fresh is a cascade of headlines, but in the form 140 characters, as the links that are pulled in use the text of the most prominent tweet on a particular story. “We want this to look like a conversation, we don’t want this to look like a bunch of headlines,” Marstall said. Keeping in that theme, each story pulled into 61Fresh shows a roster of people who have tweeted the link, as well as Twitter prompts to reply, retweet, or favorite. One interesting feature on 61Fresh is the “mute sports” button, which, as the name implies, lets users excise anything related to sports from their feed. “Early on, we realized the sports stories could really dominate,” Marstall said. “I like it — I’m a sports fan — but I know for a lot of people it’s total noise.” Ali Hashmi, a former Knight fellow at the Globe Lab who is now at MIT, created a natural language processing system that helps the aggregator parse sports from the rest of the news. Using a base set of 1,000 sports stories, the system learns how to spot a sports article and pluck it out of the stream of stories, Marstall said, if you want neither pucks, punts, nor pitchers. 61Fresh is one of the latest projects to come out of the partnership between the Globe and MIT’s Center for Civic Media. Originally, the lab’s creative technologists and Knight fellows from MIT were working on a way to archive Globe reporters’ tweets from the Boston Marathon bombing. Lessons and code from that were put into use for 61Fresh, Marstall said. This is not the first time the Globe Lab has experimented with social media feeds as a means of monitoring life in Boston. Previously the lab developed Snap, a tool that maps Instgram photos to their geolocated spots around the city. Jeff Moriarty, the Globe’s vice president of digital products and general manager of Boston.com, said 61Fresh “fits in with the idea that we’re moving Boston.com to include more of what people are saying and what people are doing right now in Boston.” With the split between the two Globe sites, Boston.com has been focused on news and information, but also digital tools and online discussion, Moriarty said. The central idea is to be able to give readers a sense of what they need to know in a format that works best for them. “By combining both the news and what’s popular on Twitter, you get this pretty unique view of what’s happening right now,” Moriarty said. At the moment, 61Fresh is a little rough around the edges, the design is not particularly eye catching, and the team at Globe Lab is catching problems as they arise. But the lessons from the project will be applied in the future, either for a stand-alone aggregator or built into parts of Boston.com. Moriarty said he thinks the project can have a lot of value for niche topics like sports or technology — pulling in tweets and headlines for a Boston audience interested in the NFL or biotech, for instance. As Moriarty sees it, the job of Boston.com isn’t just to deliver the news, but to provide context, conversation, and the other pieces to help readers see the bigger picture. “I think it really needs to be what we do as a media organization: People want someone to help them make sense of what is going on around them,” Moriarty said. |

| Nextgov’s new iPhone app is en Fuego Posted: 23 Sep 2013 06:43 AM PDT Or, rather, Fuego is en Nextgov’s new iPhone app.

(If you’re unfamiliar, Fuego defines and tracks a community of interest on Twitter — in our case, people interested in talking about the future of news — monitors their tweets, and tracks the links being talked about most. As we like to say, Fuego stays on Twitter all day so you don’t have to.) Nextgov’s app uses OpenFuego to monitor the conversation going on in the gov/tech space and produce a “Trending” tab — real-time aggregation done by the community. We’ve heard from a number of people working on cool projects with OpenFuego (and we’d love to hear from more!), but I think this may be the first time it’s been put in a shipping app other than our own. Huzzah! And congrats to OpenFuego coder-in-chief Andrew Phelps. Press release below, emphasis mine.

|

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

The

The