Nieman Journalism Lab |

- Nonprofit, for-profit, and all the shades in between: How to choose what kind of civic-minded news organization to start

- Upworthy has a recipe for chocolate-covered news broccoli that actually tastes delicious

- The newsonomics of aggressive, public-minded journalism

| Posted: 01 Nov 2012 10:30 AM PDT How to structure the organizations that produce journalism used to be a pretty simple question. Phase 1: Start a for-profit corporation. Phase 2: ? Phase 3: Profit!. But as business models shift — and as nonprofit journalism continues to take up a larger (and more valuable) piece of the media pie — aspiring media moguls have an array of business entities available to choose from. A not-for-profit 501(c)3? A for-profit S corp or an LLC? A socially conscious B Corp? An L3C? A nonprofit that spawns a for-profit? In Delaware or in your home state? A 501(c)3 that starts its own 501(c)4? The options are dizzying; each comes with its own set of obligations and drawbacks, and many live at awkward intersections of state and federal law. That’s why I’m glad our friends at Harvard’s Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations asked Marion Fremont-Smith to speak about:

We’ve spoken with her before about these questions, but here she runs through the issues someone planning a new organization should be considering — and there are some interesting questions from the audience, starting 44 minutes in. Her focus here isn’t limited to news organizations, but the lessons are highly applicable. The issues may be a little arcane to someone who isn’t in startup mode — but if you are, but it’s worth a listen. It might even save you a billable hour or two. Note: Not much happens in the video, visually speaking, so if you just want the audio, here’s an MP3. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Upworthy has a recipe for chocolate-covered news broccoli that actually tastes delicious Posted: 01 Nov 2012 09:00 AM PDT Imagine coming up with 25 distinctly different headlines for each and every story you file. Insane, right? Maybe, but it’s a key part of the strategy at Upworthy, the still-pretty-newish site devoted to sharing meaningful content and getting other people to spread it. Before settling on “What Are Selena Gomez And Justin Bieber Doing In The House Of Representatives?” the team at Upworthy drew up more than two dozen alternate headlines for this video: Here’s how they brainstormed (bold indicates Upworthy staff favorites):

2. Can You Spot The Celebrity Immigrant? 3. Racial Profiling Celebrities: Arizona’s ‘Show Me Your Papers’ Law Fails This Test 4. NO, REALLY: Senator Asks The House To Spot The Immigrant 5. Who Is A Prouder American: Selena Gomez or Justin Beiber? 6. Senators Play “Pick Out The Immigrant” In The House of Representatives 7. Do You Think The Founding Fathers Imagined A Future Where Senators Played “Pick Out The Immigrant” In The House Of Representatives? 8. Would The Founding Fathers Be Proud Of The Fact That Our Political System Has Come To This? 9. What Are Selena Gomez And Justin Bieber Doing In The House Of Representatives? 10. Watch Your Senators Play “Pick Out The Immigrant” In The House Of Representatives 11. How About We Teach Arizona’s Cops Not To Be Racist Instead Of Wasting Tax Dollars On Photos Of Selena Gomez And Justin Bieber? 12. Why Isn’t Justin Bieber Proud To Be American? 13. Don’t You Just Love When Senators Get So Angry Their Sarcasm Shows? 14. What’s Wrong With Arizona’s ‘Show Me Your Papers’ Law? Rep. Gutierrez Explains…With Sarcasm! 15. Don’t You Just Love When C-SPAN Gets Sarcastic? 16. C-SPAN Channels TMZ As Senator Uses Selena Gomez And Justin Bieber To Make A Point About Racism 17. C-SPAN: Sarcastic Senator Steals The Show 18. C-SPAN Is Usually Pretty Boring. This Is Not. 19. Sweeps Week C-SPAN: Featuring Selena Gomez, Justin Beiber, and Sarcasm! 20. What Do Geraldo Rivera, Selena Gomez, Jeremy Lin, And Sonia Sotomayor Have In Common? 21. Sarcastic Senator Steals The Show With Sonia Sotomayor And Selena Gomez 22. Sarcastic Senator Steals The Show 23. If You’re A Senator And You Want My Support, Be Sarcastic On C-SPAN. 24. Spot The Celebrity Immigrant And You Could Be An Arizona Police Officer! 25. Cool Senator Or The COOLEST Senator? (And yes, for the record, Luis Gutierrez serves in the House of Representatives, not the Senate. Give them a break — it’s brainstorming!) Why spend so much time tweaking a headline? It’s all part of the Upworthy mission to make meaningful stories go viral. So far, it’s working. The site expects to notch 7 million uniques in October. It already has more than 400,000 Facebook fans, all with a fledgling staff of about a dozen people, and in just seven months since launching at the end of March. “We really didn’t know if this would work at all,” cofounder Eli Pariser — perhaps best known for his work at Moveon.org and his book The Filter Bubble — told me. “We’ve had lots of meetings with people who have been in the media industry for a long time who were like, ‘Yeah, good luck.’ Everybody’s trying to somehow cover the broccoli with chocolate sauce and make it go down easier, and you end up with something that tastes horrible. It’s been so awesome to see the hunger that people actually have for content that does have meaning. That’s what gets me so excited: proving the thesis that people don’t just want fluff stories. People do actually want to be engaged, and treated like adults, and thinking about interesting and thoughtful stuff.” Take a look at this growth:

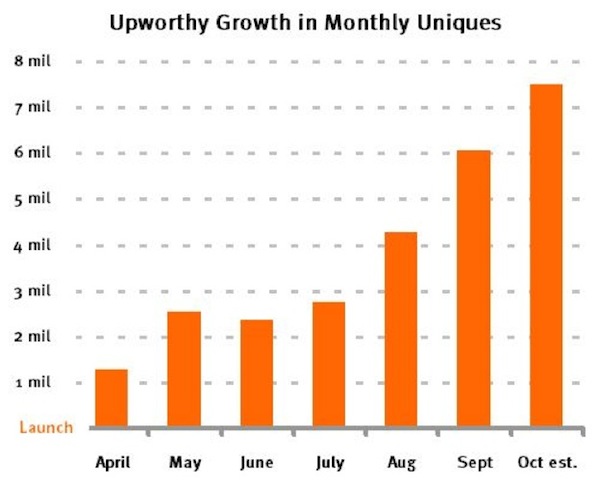

Those graphs would seem to validate Upworthy’s assumptions about how virality works — that online packaging and distribution are as important as having quality content in the first place. That might sound painfully obvious: What good is stellar reporting if you can’t get it in front of people’s eyeballs? But many news organizations still appear to treat social packaging and distribution as an afterthought. You spend days reporting and writing a story, minutes coming up with the headline, and seconds tweeting it. At Upworthy, there are three equally-important priorities for each “nugget” of content — many nuggets are video clips — to use the in-house terminology:

Let’s break it down some more. What kind of content matters? That is, what does it take for something to be deemed Upworthy? “I think about that in a couple ways,” Upworthy cofounder Peter Koechley told me. “One question that we ask our curators to ask themselves is, ‘If 1 million people saw this, would it make the world a better place?’ which allows for a lot of interpretation. Curators could disagree on that.” That’s a good thing: If curators have to make the case for a video clip internally, they’re forced to be thoughtful and persuasive about why it’s worth sharing. While Upworthy explicitly seeks content that will elicit an emotional reaction from those who encounter it, something that’s straight-up heartwarming or entertaining might not make the cut. That’s why President Barack Obama doing his best Al Green didn’t fly. (Pariser explained: “I got a kick out of that video, but is it meaningful? Not really. It’s kind of presidential celebrity.”) For a video to be quintessentially Upworthy, it has to resonate broadly and deeply. Take, for example, this video clip of a Wisconsin news anchor addressing the viewer who called her fat. Just check out the traffic spike Upworthy got once it posted that video:

Ultimately, Upworthy drove about a quarter of the hits that this video got — “significantly more than Mashable, Reddit, People.com, BuzzFeed, and other sites known for their traffic-driving prowess,” according to Upworthy’s Maegan Carberry. Check out this graph by Stephan Daniel, who posted the video first and shared these analytics with Upworthy:

Whereas BuzzFeed’s founder has talked about the bored-at-work audience as one of the site’s key networks, Pariser sees Upworthy’s crowd as a distinct yet similarly social audience. “We see ourselves as serving a somewhat different but equally powerful network, which is like a searching-for-meaning network,” Pariser said. “People who want to be part of something that feels like it has a purpose. And that’s actually a big ecosystem of people and of content. It’s also content that doesn’t have a traditional audience or place to go. So partly what we want to build is to strengthen or amplify that network.” Upworthy takes some stances on broad issues — equality is good, bullying is bad — but tries to stay away from the nitty-gritty of partisan politics. Striking that balance isn’t always easy. One example is this video of a bold speech by Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard: Gillard’s speech was political. But especially to a global audience, there was something about it that felt bigger than, say, Gillard’s political record against same-sex marriage. That something bigger was what Upworthy wanted to share. Here’s how Upworthy community manager Kaye Toal explained it to me in an email:

The team at Upworthy is obsessed with sharing content that roils emotions, and equally fixated on the data it collects along the way. Hong Qu, who is in charge of user experience for Upworthy, says part of his job is approaching virality as a science. “Not every story will have the same exact resonance with your audience,” Qu told me. “If you do see one that’s an outlier that’s taking off, you shouldn’t just be happy and look at it and say, ‘Congratulations.’ You’re missing the opportunity to tweet it to so many people — to send it to all the people you have. There’s a theory in psychology about why people try new things and adopt new behavior. When they see three of their trusted friends recommend something to them, that’s the effect you want to induce artificially. You’re manufacturing virality.” For Qu, who says his graduate degree in social psychology guides much of his thinking about Upworthy, considering why people share content is as important as making content worth sharing in the first place. “We care about shares because that’s how we acquire new customers,” Qu said. “You have to attract people to walk in the door. For a storefront, it’s very easy. What’s the equivalent of that in digital space? We have a pretty sophisticated algorithm, like a radar detection system for how shares are doing, how a particular article drives more customers.” Instead of looking at audience the way a television broadcaster might describe reaching 10 million homes, Upworthy looks at its audience through what it calls “generational analysis.” Generation one is the group of people who get content directly from Upworthy, generation two refers to people who get content from the first generation, and on and on and on. Upworthy says it has tracked generational shares into the twenties. And while Qu says “no one else is really even close” to such sophistication in measuring how audiences interact with content and one another, the big question that’s still without a precise answer is why something goes viral at all. “Sometimes it’s a mystery to me why something gets so many generations,” Qu said. “We can tell how many people are sharing it, but we can’t really tell the sentiment, which side they stand on, what they say about the story itself.” (To help figure out how people feel when they decide to share, Upworthy is working on a feature that will let audiences vote — not unlike Rappler’s Mood Meter and other newsy mood experiments.) Qu says he has a long wishlist of features to develop. He wants to make an “Upworthy” button that might go next to the Facebook “like” button. He likes the idea of real-time, public virality statistics, so viewers can see if something they’re watching is going viral as they’re encountering it — the idea being that people like to feel as though they’re part of something. Qu admits that it can be scary to think about building something for the site that might take even six months — from a development standpoint, rapid iterative development is key to staying ahead of the curve. But Upworthy is not beholden to the time constraints that most newsrooms face. (And remember, Upworthy isn’t a newsroom, as its staffers repeatedly emphasized.) When it comes to content, Upworthy won’t hesitate to share a video that’s years old if it’s the best way to capture the zeitgeist. “We do try to hit timely news cycles,” Toal said. “The Todd Akin thing, we were all over that. But you can pull up older content to talk about those same things, the same way you would in a conversation with a friend. If news organizations are about keeping you up to date, Upworthy is more about reminding you what matters, and introducing you to other things that matter.” This mentality fits with the site’s revenue model. Upworthy gets funding from sponsor partners who pay for affiliation to certain content — and, in turn, access to a certain kind of audience. An environmental group might want to give people the opportunity to sign up for its newsletter after an environmentally-themed video. A group that aims to increase voter turnout might sponsor a video related to that issue. The approach to sponsorship is another way that Upworthy is BuzzFeed-esque, as sponsors are deliberately paired with content. The difference between BuzzFeed and Upworthy, as Toal describes it: BuzzFeed might post eight pictures of Lady Gaga dressed in meat, whereas Upworthy would post eight ways being dressed in meat affects the poor. If the big question is what makes something go viral, the even bigger question is how do meaningful viral videos translate into real-world action? “It’s hard to measure,” Toal says. “It’s not like we can go to each of our Facebook fans and ask, ‘What have you done today?’ We’re thinking about that more. But the other thing is, I think the unvoiced part of that question is whether or not sharing something on Facebook is inherently less valuable than going door-to-door. I’m not convinced that it is. Either way, you’re educating.” So while Upworthy is decidedly not a news organization — although hasn’t ruled out a future that includes original reporting; note today’s post featuring “Upworthy’s first-ever real live actual poll of swing-state voters” — the site clearly shares some of journalism’s core values. As cofounder Pariser puts it, they’re also some of the loftiest. “To put it in sort of hopelessly, naively idealistic newsroom terms, we do believe you need an informed citizenry to make decisions in a democracy,” Pariser said. “And if you do that well, then good things will come. That’s sort of the article of faith for us. If you can actually bring something like childhood poverty in America to people’s attention, people want to do something about it. The reasons those problems don’t get fixed is mostly that they don’t get noticed, because Kim Kardashian is getting noticed instead.” |

| The newsonomics of aggressive, public-minded journalism Posted: 01 Nov 2012 07:30 AM PDT “I don’t care about a business models for newspapers. I care about my son’s future.” Those words from Grzegorz Piechota, head of news for Poland’s Agora SA and news editor at its flagship daily Gazeta Wyborcza, clearly struck a chord with a recent newspaper audience in, of all places, Sydney, Australia. Piechota, who took on the presidency of INMA (International Newsmedia Marketing Association) Europe board in 2008, painted an ambitious picture of involved community journalism as a way to the industry’s future.

What made Piechota’s talk stand out was his focus on community and the aggressive public journalism his company practices. One of the projects he focused on was education reform. School 2.0 included lots of reporting and liveblogs and, most importantly, involved 650,000 Polish teachers in the project. Over 7,000 schools participated. “You need to flood the zone,” says Piechota, borrowing an American football metaphor for impactful journalism. His talk — worth watching here — offers a primer for editors on participative journalism and on the use of physical events. Gazeta sponsored 630 of them last year, with 120,000 participants. “Give people tools and inspire them,” he says. Gazeta Wyborcza’s latest social campaign launched in September. It focuses on a topic familiar to Americans: childhood obesity. “It raises awareness about spreading obesity among Polish kids and addressing the problem from food (quality of food at schools, quality of cheap food that poor people eat) to fitness (quality of fitness lessons in schools, effectiveness of government programs to promote amateur sports, etc.),” says Piechota. “The campaign is based on series of stories across Gazeta’s channels, cooperation with other media (TV and radio channels, magazines, bloggers), an educational programme for Polish teachers (schools can join the program for free) and PR events like public cooking at the biggest rock music festival in Poland.” Gazeta Wyborcza (or Electoral Gazette), the second-largest Polish daily behind the tabloid Fakt, in a nation of about 36 million. It has a special birthright: The newspaper grew out of the Solidarity movement and, when launched in 1989, was the first paper since the start of the communist regime to be published legally without goverment control. Peter Richards, who has worked in communications in central and Eastern Europe since 1992 and is now Piano Media’s country manager in Poland, offers this perspective on its role:

Piotr Ambroziak, a former commercial director with the Polish news agency PAP and now working at the European Pressphoto Agency, remembers that 1994 “Childbirth with Dignity” campaign well:

Ambroziak also speaks to Gazeta’s reporting style: “Gazeta always represented very engaged journalism — they were never neutral.” Make no mistake: Piechota is among the first to say that finding sustainable business models is paramount, and that companies that care about news must remain profitable. Gazeta Wyborcza (circulation 306,000 as of 2011) is struggling with the same advertising and print circulation declines as its peers to the east and west. It’s cutting staff, as it along with other Polish quality dailies see readers flee print. Its Internet portal Gazeta.pl is highly popular, but isn’t coming close to making up for print declines. In the first half of 2012, advertising spending for all Polish media decreased by about 4 percent. Digital is up 10 percent, with dailies down 18 percent and magazines down 9 percent, according to Agora. Its profit margin is down to less than one percent, although it has tried diversifying in a range of classified, movie, talk radio, book, and other businesses. Like all newspaper companies, its future is not assured. Notes Piechota candidly: “In Eastern Europe, if you’re not profitable, you’ll be bought by oligarchs or political parties.” But Gazeta Wyborcza pulls no punches in believing its brand of what many would term advocacy journalism is also its route to business success. Connecting the dots of its editorial strategy and its business results is much more elusive. “Positioning as a public advocate is the backbone of this newspaper,” Piechota told me this week. “It was not launched just to make money. It was founded to bring democracy to this country and to build an open society. We help to bring change by providing honest journalism and tools for driving people’s engagement into issues that affect them. Being close to people gives us a credibility that advertisers want to share. You cannot divide that.” This is a View from Here, a View from Somewhere — the kind of departure from the View from Nowhere, described for the ages by Jay Rosen and demonstrated so painfully in Jim Lehrer’s first-debate “moderation.” Let’s be clear. We see lots of good passionate journalism in the United States. CNN, which has been unable to find its way out of the muddle of election debate, has shown its passion well in condemning human trafficking through thorough journalism on the topic. Each year’s list of Pulitzer winners shows that dedication, as does the work of the higher profile national nonprofit investigative outfits, from ProPublica and the Center for Investigative Reporting to the Center for Public Integrity and Investigate West. We see the spirit running through many of the members of the Investigative News Network; I think the St. Louis Beacon’s “A Better Saint Louis” top-of-the-page position sums up the Gazeta spirit well. As for American dailies? Most do a good job of day-in, day-out coverage, and many still hit high spots with series as they fight to eke out the time out of diminished staffs. It’s not that good, passionate work isn’t done — it’s just too often the exception. It’s not the driving raison d’etre it is with Gazeta. Maybe, just maybe, part of the strategy going forward should borrow from Gazeta. As Rosen has articulated well over the years, joined by many choruses, the “objective” journalism that accompanied newspapers’ post-World War II boom long ago outstayed its welcome. As editors of monopoly dailies struggled to be “fair,” many lost sight of their responsibilities to help lead communities in problem solving. People don’t just want endless problem describing — especially wrapped in the guise of “two sides.” The war over the “lamestream media” consumed much of the news blogosphere for far too long, as the production of news diminished and diminished. Now it’s time — in an age of readers paying for much more of the news they get — for editors and publishers to think more about community service. We’re not talking about political advocacy. We’re saying: education should be better for our children, global warming needs to be addressed, and better health care for everyone. Let’s ditch the two-sides divide — the silliness of the left-right dance, which doesn’t really describe the world we inhabit — and move on. For newspapers, Gazeta says, the chance to lead is the chance to publish and to survive. My sense is that they’re right — though they’ll only succeed if the company’s business strategies harness the same kinds of intelligence as do its editorial ones. Piechota’s words are oddly resonant in the U.S. this week, a few days before our presidential election. Whatever our partisan beliefs, it’s clear this has been a Seinfeldian campaign, publicly about nothing. Both parties, for reasons of their own, have failed to offer roadmaps to solutions to the very real issues before the voters. Journalists, even as some try to break out of the horse race, are correctly seen by their publics as more about the problems than of the solutions. For us, the lights of that 1776 revolution burn dimly; for Gazeta, 1989 is well within memory and still motivating. So what are the newsonomics of Gazeta’s aggressive public journalism? They’re a work in progress. As Piechota notes, you can’t single out one series or project and tie it to financial consequence. In the end, we’ll only see, over time and by inference, the causes and effects as Gazeta struggles to pay journalists to their work. One early indicator will be Gazeta’s performance with Poland’s new pay-for-news network. It’s the lead daily, and the group of seven media companies in the pay-once-a-month, access-all system include Polish National Radio, the national daily Super-Express, 20 regional newspapers, and a number of lifestyle and business magazines and online-only publications. In all, the network touts “42 websites with over 119 different sections.” Given that it’s only six weeks old, performance is unclear. But Piano’s model rewards publishers who win most usage through the network. (Piano Media, the European counterpart to Press+, is now itself moving aggressively beyond its first three networks in Slovakia, Slovenia, and Poland. This week, it acquired Novosense, which it says will allow it to power metered systems for individual publishers.) This has been the year of reader revenue initiatives (“The newsonomics of majority reader revenue”), and Gazeta’s approach fits neatly into that emergent strategy. If you’re going to charge readers — and, increasingly, charge them for digital plus print access — then the quality of your journalism and readers’ perception of its value rise to the fore. The synergy here shouldn’t be missed by any newspaper publisher. This is the snapshot of our new news world. A Warsaw editor enlivens a newspaper crowd in Sydney, some 9,600 miles and 20 hours away. In this news revolution, we all have much to learn from each other, and the old national boundaries no longer apply. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

The September

The September