Nieman Journalism Lab |

- Now playing: The New York Times signs on to Hulu to reach a new audience for its long videos

- How important are all those ugly Tweet Buttons to news sites?

- The newsonomics of majority reader revenue

| Now playing: The New York Times signs on to Hulu to reach a new audience for its long videos Posted: 31 May 2012 11:30 AM PDT

You can now find videos from The New York Times on Hulu, thanks to a content licensing agreement between the paper and the popular video site. Video produced for NYTimes.com will now be available alongside episodes of Modern Family, Glee, or old eps of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. More likely, they’ll be in the same neighborhood as documentaries and short news videos. The Times joins a number of news outlets on Hulu, the obvious ones like ABC News, NBC News, and Fox News, but also The Wall Street Journal. The first Times video on Hulu is “Punched Out: The Life and Death of an N.H.L. Enforcer,” which was produced in conjunction with their three-part series about hockey player Derek Boogaard, who died at age 28 last year. The new Hulu channel will be a destination for Times videos that are more like short documentaries — maybe things like the Last Word series or Op-Docs. When I spoke to Ann Derry, head of the video department for the Times, she said we can expect to see more videos soon on Hulu. “We’re always looking for ways to raise the visibility of what we do and get a larger audience,” Derry said. Derry told me the Times and Hulu had been in discussions for some time. They chose the Boogaard video both because its length (36 minutes) fit well into Hulu format and because it’s the time of year for the NHL playoffs, meaning there’s a chance to grab the attention of enthused hockey fans. Derry said Hulu is the right fit for Times videos like “Punched Out,” which Derry estimates took four months to produce in concert with the story on Boogaard. Producer Shayla Harris and videographer Marcus Yam worked on the video as reporter John Branch reported out the story, which details Boogaard’s career as an enforcer and the effect it had on his life. When the story was published in December 2011, it was accompanied with “Punched Out” in three segments. In moving over to Hulu the video has been repackaged as a single film to better fit the viewing experience on the site. For the Times there are obvious costs and benefits in joining up with Hulu. On Hulu, a viewer may be more likely to seek a lean-back entertainment and watch a video longer than five minutes. But by putting the videos on Hulu, the Times is also sending eyeballs off their property and adding an intermediary who’ll expect a cut of the ad revenue. Derry said that’s not a big problem. “It’s always been both our journalism and business strategy to have people watching videos on our site and off our site,” she said. Hulu clearly offers the potential for new viewers to stumble onto Times videos who may have never visited NYTimes.com. Derry doesn’t see it as a zero-sum game. She said the new Hulu channel can add more awareness of the Times for viewers. “One doesn’t have to take away from the other,” she said. In the grand scheme of online video, moving to Hulu may not hurt. According to comScore the average online video viewer watched 21.8 hours of video in April, with Google sites (YouTube) making up 7.2 hours and Hulu accounting for 3.8 hours. The Times’ videos are also available through Hulu Plus, which lets Times video appear on TV sets through devices like like Roku, Xbox and the Nintendo Wii. (Longtime Nieman Lab readers might remember back in 2009, when the Times’ R&D Lab was busy thinking about creative ways to get Times multimedia content into people’s living rooms. Hulu Plus is one route.) The Times still has a ways to go to catch up with The Wall Street Journal here, though, with its dedicated WSJ Live app and its dedicated channel slots on additional devices like Apple TV and Google TV. This isn’t the first time the Times has syndicated their video content elsewhere, as anyone who’s flown JetBlue can tell you. The Times has a YouTube “edition” for the paper’s videos. They also had the short-lived Discovery Times cable channel. Derry got her start making videos for Discovery Times, and she said working with Hulu could be a return to producing those kind of projects for the Times. The newspaper creates many hours of video, ranging from daily news programming with TimesCast and Business Day to interviews with newsmakers and series like The Last Word. Since Hulu is a home for episodic content, it would make sense for the Times to add their more episodic offerings like Tony Scott and David Carr hamming it up, to their Hulu library. But rather than just dump a big chunk of the paper’s large video catalog on Hulu, Derry said they’re being selective about what content fits there. The Times will soon have more video on Hulu and Derry hopes they’ll broaden their offerings to produce more longer pieces. “All of a sudden, you’re broadening the options of the things you can do,” she said. For Hulu, just like NYTimes.com, Derry said the main question remains the same: What’s the best format to tell a story? |

| How important are all those ugly Tweet Buttons to news sites? Posted: 31 May 2012 10:23 AM PDT

In some ways, it’s not as bad as it used to be, when there were more social networks making a plausible claim on people’s attention. (Digg that!) But even in a world that’s mostly shaken out to Facebook and Twitter — plus maybe Google+ if you’re generous, or LinkedIn if you write about business, or Pinterest if you’re about shopping or food, or…sigh. Well, even in a world that’s mostly shaken out to a few social networks, those buttons are still a less than appealing set of warts on the body hypertext. That’s the argument advanced by designer Oliver Reichenstein in a blog post (“Sweep the Sleaze”) that got a lot of attention this week:

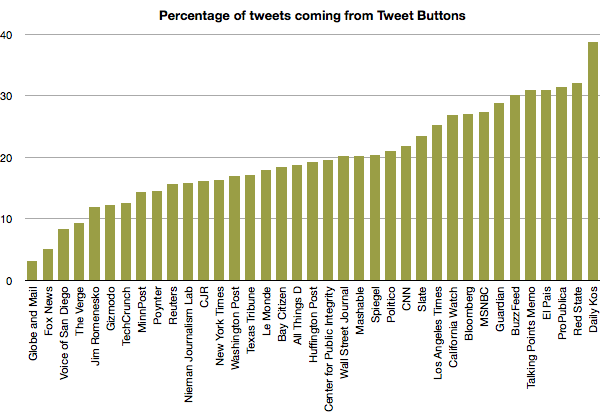

Not surprising, coming from a designer best known in the technology world for building a minimalist writing app. But do those Like buttons and Tweet Buttons do any good? To get some data on that, we can thank Luigi Montanez, who posted a Ruby script that allows you to see, of the n most recent tweets containing a given URL string, how many of them were generated by a Tweet Button. (More detail here.) Luigi found that there’s substantial variation among different sites. I downloaded the script and decided to start running it on a variety of news sites to see if I could suss out any patterns. This isn’t hard science, for reasons I’ll get into in a moment, but it’s interesting! Here are the results from 37 news sites, first divided up by type of news site. (I looked at the 1,000 most recent tweets for each, rather than Luigi’s 500.)

The Y axis is the percent of the 1,000 most recent tweets that Twitter says were generated by a Tweet Button. So, 16.3 percent of those tweets to nytimes.com (The New York Times) came from such a button, versus 20.2 percent for wsj.com (The Wall Street Journal). Two broad observations: — Tech sites seem to be less reliant on the Tweet Button, as a percentage — as one might expect from sites with a social media-savvy audience. Presumably readers of The Verge are comfortable copying and pasting a URL into Twitter on their own, or tweeting to Verge content by seeing someone else’s reference to it in their feed. — Sites with a clear ideological profile — Daily Kos on the left (38.8 percent) and Red State on the right (32.1 percent), for instance — are among the heaviest beneficiaries of the Tweet Button. Could that be because their readers are explicitly looking to those sites for links to share on their networks, and the Tweet Button is an easy way to speed up that process? But Fox News seems to be an interesting exception to that observation — only 5.1 percent of its tweets came through the button, versus 27.3 percent for MSNBC. Most other sites seems to fall into a broad middle, which makes sense. Here’s that same data, but this time ordered by percentage rather than grouped by type of outlet:

All right, let’s all visit Caveat Central — a place of particular interest to any journalism graduate student who’d like to tackle this in a more serious way and get a good AEJMC paper out of it: — This is just a snapshot of 1,000 tweets’ worth of data, taken around 11:30 a.m. ET today. You’d need a much bigger data set to do any serious analysis. The numbers could be substantially different at a different time of day or day of week, for instance, or at different points in a story’s life cycle. You’d also need to get raw counts over time — “the 1,000 most recent tweets” might cover a span of 15 minutes for some sites and several days for another. — This script doesn’t measure other Twitter app data — in other words, how many are using the Twitter iPhone app, how many are using news org-branded apps, how many are using TweetDeck, how many are using Twitter’s web interface? Lots of interesting data potential in there. It would also be interesting to correlate the results with each news org’s own Twitter presence; The New York Times’ 5.1 million Twitter followers no doubt make Tweet Button usage seem smaller in comparison. (It’s also worth noting that some sites may have something that looks like a Tweet Button that’s actually registered with Twitter under a different app name; those wouldn’t show up here.) — Not all Twitter users are created equal, of course. How do the Tweet Button users compare to those using other means to tweet — particularly in the size of their Twitter followings? If Tweet Button users were numerous but had small followings, they might not be as valuable to news organizations as they’d seem at first glance. — To do this justice, you’d also need to analyze placement of Tweet Buttons on sites. Audience composition isn’t the only reason Tweet Button behavior might change, of course; potentially much bigger is the placement of Tweet Buttons on each site. (Just below the headline? At story’s end? Both?) But even this quick look would seem to support the idea that killing off Tweet Buttons would, for most news organizations, remove somewhere around 20 percent of their Twitter link mentions. Maybe more, if (as I’d guess, although with no data) that those Tweet Button users are often something like a Tweeter Zero — an originator that enables a story’s later spread through other means. (Here’s where a tool like the Times’ Cascade would be really useful.) Or maybe less, since some percentage of those Tweet Button users would still find other means to tweet without them. Here’s hoping some Ph.D. student runs with this. |

| The newsonomics of majority reader revenue Posted: 31 May 2012 07:38 AM PDT

Who would you rather support journalism, advertisers or readers? It’s a new question, one that made less sense to pose just three years ago. Now, though, with major shifts in the news market, it’s one to think about. We’re about to move into a period in which reader revenue surpasses advertising revenue as the main support of many news(paper) companies. It’s yet another kind of profound crossover (“The newsonomics of crossover”), demonstrating again how quickly news business models are changing. With readers paying most of the freight comes a new series of profound questions, ones that we should start asking as we try to understand this change. Unexpectedly, newspapers — of all things — are becoming the leaders in reader-supported media. As the public journalism movement (the enterprising start-ups led by the likes of The Texas Tribune, California Watch, and MinnPost) and public media (née public radio) pioneers move to increase their share of reader funding through voluntary membership (read subscription), newspapers are, almost accidentally, leading the way. The reason is obvious: There are millions of people used to paying for news — and now, courtesy of mobile news proliferation and All-Access plans — their expensive subscriptions are being ported over to the digital world. How much money are we talking about? Worldwide, according to research I’ve done in my work with Outsell, circulation revenue — worldwide in 2011 — totaled about $30 billion. In the U.S., daily circulation revenue probably adds up to about $9.5 billion. That’s a large sum, and it’s a key puzzle piece for the future. Is it true digital revenue? Well, of course not. Does that matter? Where newspapers started bundling advertising — print, with a little digital — in combined buys in the ’90s, now they’re bundling print + digital subscriptions, even as they also sell “digital only” ones. All-access models make for a new indistinguishable blur — are people paying for print, for digital, or for news itself? — and that’s a head-turner. It shouldn’t be a head-turner just for those of us watching the trade. If you run The Huffington Post, or Slate, or Examiner.com, you’re betting on one big revenue stream — digital advertising — going forward. Though there’s a huge amount of money in digital advertising, more than 70 percent is going to companies with the combinations of great audience reach and mind-boggling targeting ability. So, as Facebook shares tank this week, amid concern of it being able to compete well enough to justify its value in the hypercompetitive and cutthroat ad market, think of the smaller news players, like HuffPo, and their relative digital ad revenue prospects. If they’re competing in the 2015 marketplace with one revenue stream — digital ads — while whatever we call “newspaper companies” can harness two revenue streams, overall reader revenue and advertising, who has the advantage then? (Facile answer: It depends on how quickly legacy newspaper companies get rid of legacy newspaper costs. Witness Digital First Media and recent Newhouse/Postmedia day-cutting moves. In fact, the Postmedia moves with major Canadian properties — drop days, charge for digital access, centralize whatever can be centralized — are prototypical of how this new world fits together.) That new twist to digital news competition is one I’ll return to soon. For now, let’s understand this inexorable run toward majority reader revenue. The trend has been slowly developing over the years, and now has picked up speed, because of two trends.

For decades, the rule among newspapers in the U.S. was 80/20. Eighty percent of revenue came from advertising and 20 percent from circulation, with the circulation revenue — heavily home delivery subscriptions in most markets — paying for all those physical costs of getting the ad-heavy product printed and delivered. The great majority of the revenue — and significantly, the 20-35 percent margin profits — came from advertising. In Europe and the U.K., the traditional model has been less ad-heavy. Figure that 25-40 percent of revenues have been derived from circulation, with great variation by region and market. In Japan, thanks to both high pricing and enviable Amway-like network of paper deliverers and bill collectors, readers have long contributed the majority of revenues. Japan, though, stands out as the exception. Now the exception is building a new rule. Take one good Midwestern example: Minnesota’s Star Tribune, fairly typical of once highly profitable, mid-sized metros. Like most of its peer group, it would have derived around one in five dollars from readers for many decades. Now, according to publisher Mike Klingensmith, the total is up to 43.3 percent; a number that he knew instantaneously when asked. “We will definitely be at 50-percent-plus reader revenue in the next 18-36 months,” he tells me. It’s not magic; it’s math. We go back to those two principles: fast-declining print ad revenue and new, all-access-inflected digital circulation. “We don’t want to hit the 50 percent too quickly,” Klingensmith adds with a chuckle. That would mean that print ads continue, or deepen, their downward trajectory. As those revenues tumble, of course, their percentage of the revenue contribution declines. That’s a no-brainer. The other part of the equation, smart reader revenue management, is more interesting. At this point, publishers have figured out that there are two ways to wring out more reader revenue. Charge print subscribers a little extra for digital reading. Many of the Press+-powered papers, including the Baltimore Sun, charge print readers an increment — in the Sun’s case 99 cents a month extra. That adds a new increment to print circulation revenue and has helped at least stabilize circulation revenues at many of the papers that charge, or in some cases boosted it 1-3 percentage points. Klingensmith takes a different approach. He increased pricing for all print subscribers by 9 percent in April 2011, at a time when digital access was still free. Then, last fall, he introduced a metered paywall, offering subscribers who take print at least two days a week (Sunday-only subscribers still must pay extra) included free digital access. The result: a 7.5 percent increase in circulation revenue in the first quarter. That compares to a low-single-digit decrease in ad revenue. The lines on the graph are converging. If you do it right, he says, you can keep your revenues growing. “If you support a 10 percent higher price [overall], you can generate much much more income than selling 10 percent of your subscribers digital access,” says Klingensmith. What does doing it right mean? On the reader revenue side, it means a bunch of things, including smart pricing (“The newsosnomics of pricing 101″; “The newsonomics of 99-cent pricing”), a state-of-the-art customer database, mobile products (HTML5, app, or both) that provide real value for higher pricing, and substantial enough journalism to make it all work. Of course, containing ad revenue decreases — hold on to as much of print, try to grow digital advertising faster — as much as you can is a vital piece of the puzzle. The Star Tribune’s math is among the most aggressive, but it’s got plenty of company in the reader revenue march to majority. Take A.H. Belo, owner of three major papers, The Dallas Morning News, Providence Journal, and Riverside (Calif.) Press-Enterprise. In the first quarter of 2011, circulation contributed 34 percent of combined ad/circulation revenues. (I’ve eliminated “other” revenue from this calculation here and elsewhere to focus in on the ad/circ change.) A year later, circulation now contributes 36.5 percent. That’s a combination of aggressive pricing, similar to the Star Tribune’s, and the ad decline. Take The New York Times. The company as a whole hasn’t quite crossed over, but remarkably the New York Times Media Group has. A year ago, its first quarter showed 48 percent of revenues derived from readers; now that number is 52 percent. At the New England group, basically The Boston Globe and the Worcester Telegram & Gazette, this year’s split is 47 percent circulation revenue, up three points from a year ago. By way of comparison, Time Inc., a good barometer of the consumer magazine industry, clocks in at 43 percent circulation revenue now, compared to 38 percent three years ago. Magazines, of course, take in far smaller annual payments from readers, but then again their costs are much lower. They are, though, subject to parallel print advertising downdrafts. The inexorable trend of paywalls only underlines this trend and will speed the process to majority reader revenue. As we move into this age of majority reader revenue, we see a slew of new questions unearthed. For starters:

Photo by Peter Dutton used under a Creative Commons license. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

News sites today are pockmarked with sharing buttons, those little “tweet this” or “like that” rectangles attached to seemingly every story these days.

News sites today are pockmarked with sharing buttons, those little “tweet this” or “like that” rectangles attached to seemingly every story these days.