Nieman Journalism Lab |

| Politico Pro, one year in: A premium pricetag, a tight focus, and a business success Posted: 17 Apr 2012 07:30 AM PDT

Most nights on Capitol Hill, the Senate and House press galleries begin to thin out around dinner time. The deadline rush subsides, and all but a scatter of reporters remain. It was approaching 11 p.m. on March 7 when Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid announced a deal that cleared the way for voting to begin the next day on 30 amendments tied to a $109 billion transportation bill. Inside baseball, sure, but it’s news that matters inside the Beltway, and matters to a lot of people. It’s the kind of deal you might want to know about right away if you were a member of Congress or a lobbyist or someone else who has to keep track of policy for a living. But it’s unlikely you would have found out about the deal on TV, or on Twitter or via any major newspaper’s website that night. Even traditional policy publications didn’t have it. Enter Politico Pro, the pricey premium news service, launched last year with the goal of doing for policy coverage what Politico set out to do for political coverage five years ago. “I don’t think the policy areas had been covered in a very interesting way before — policy publications can be pretty dry,” Politico Pro editor-in-chief Tim Grieve said. “There are ways to cover this stuff that are pretty damn interesting, which may be the secret to our success.” On the night of March 7, paid subscribers to Politico Pro got the news about the Senate transportation deal almost immediately. Anyone signed up for the service’s energy coverage would have received this email at 10:41 p.m.:

Sixteen minutes later, Politico Pro published a story about the deal, including a full list of the amendments. Here’s a partial screenshot:

Less than an hour after that, a reporter for Politico’s core site broke the news that President Barack Obama had been personally lobbying Democrats in the Senate, urging them to reject one of the amendments that turned out to be on the list. In the span of an hour, Politico and Politico Pro — we’ll get to the distinction later — had significantly advanced a major story in a way that would inform the next day’s business on Capitol Hill. For people involved in that business, knowing about these developments before getting to work the next morning would have been key. “The next morning at 7:18, our competitor has this story: ‘Amendments for the Senate transportation bill are still up in the air,’” Grieve said. “They didn’t even have the story. That happens quite a lot…Do you want to find out something that’s really important in your universe now, or do you want to wait?” “Now” is increasingly the answer among smartphone toting news consumers. But like many premium niche news services, the nowness that Pro delivers comes with a steep price tag. A year into its life — and as more publishers consider whether a premium-content strategy might make sense for them — Politico Pro’s success is a model worth watching. You pay for what you getPolitico Pro covers four major policy areas: technology, energy, health care, and transportation. Newest in the mix is the transportation section, which launched on Tuesday. The site plans to add at least one more vertical before the end of 2012. Of Politico’s 217 total employees, more than 150 are on the editorial side, with 45 of them dedicated to Pro. The rest work in sales, technology, and events. For an individual subscribing to one of Pro’s verticals, pricing starts at $3,295 per year. But most Pro subscribers are part of a group membership, and those start at around $8,000 per year for licensing content from a single vertical to five people. Pro bans subscribers from sharing or forwarding content. Add more employees to an organizational membership and the “price becomes more fluid,” says Miki King, Pro’s executive director of business development. The subscription strategy has been somewhat fluid, too. Pro didn’t offer group memberships at first, but quickly found that it was a better business strategy. “The vast majority, well over 95 percent, are organizational subscriptions versus individual subscribers,” King says. “The whole idea behind the Pro subscription is we are going so deep in these policy areas that you would only care about it to this degree if this is your job.” So it’s not surprising that about one-third of Pro subscribers are government workers. “That ranges from Capitol Hill offices — members of Congress and senators’ offices — to government agencies to state and local municipalities,” King said. “Roughly another third are in the general public policy space — trade associations and those organizations that cover general policy, the think-tank types of organizations, or those who specifically cover energy policy.” The other third is “everybody else,” King says. Pro executives won’t publicly share subscription numbers, but just past the one-year mark, King says the figures “very quickly exceeded the expectations of where we thought we would be.” She says the number of subscribers has tripled since February 2011, and renewals “overwhelmingly” surpassed market-based predictions of 85 to 90 percent. As Politico’s Jim VandeHei and John Harris wrote in a staff memo earlier this month:

While the Politico brand has been built on breaking targeted news, the sense of urgency that guides Pro’s team is mostly about getting meaningful information to people right away — sometimes even before reporters have a full understanding of what a news development means. King says Pro has “no problem whatsoever sending out to our subscribers a two-line email that’s going to give you a piece of breaking news that could impact your day because we’re not waiting for three hours for a reporter to file a story on it.”

That also means changing the way Pro’s stories are constructed. “One of the things I tell reporters every day is: When you get to that point of the story, four or five paragraphs in, and [you write] ‘the move comes amid…’ — stop,” Grieve said. “Anybody who is reading Politico Pro knows what ‘the move comes amid.’ That 300 words of new essential information can be a 300-word story. The traditional approach would be a 1,000-word story, but the second part of that story would be the blah blah blah that everybody already knows…It’s very liberating for reporters, but it’s pretty damn liberating for readers too. No one has time to read stuff they already know. Take your time with the stuff that’s going to grab them by the jacket lapels and say, ‘Whoa, this is new.’” Pro by phoneFor Politico Pro, grabbing readers by the lapels means getting into their inboxes. Because the overwhelming majority of Pro subscribers are in Washington, that means catering to their reliance on BlackBerrys, which are — believe it or not — still ubiquitous on the Hill. “It’s such a BlackBerry-centric and email-centric world,” VandeHei, Politico’s executive editor and co-founder, told me. “Anything that moves [on Pro] you’re getting pinged to you instantly on your BlackBerry. That option is only available right now to Pro subscribers. We just hear something interesting, and it might be just enough text to fill a BlackBerry screen. That part of the experience is very different than what you’re getting from Politico.” (Although Politico’s main product puts a lot of emphasis on mobile, too.) Pro’s phone-centric approach means that its subscribers spend “very little time” on the site itself, Grieve says. There’s also no plan to move into text-messaging territory. Instead, subscribers get Pro updates on their BlackBerrys while rushing between hearings, while they’re waiting for a meeting with a Senator, or while they’re otherwise on the go. “If you have a few hours on the weekend to read a 10,000-word New Yorker story, that’s a really rewarding experience,” Grieve said. “It’s also not what we’re trying to do. If you’re racing around the Hill trying to make progress on the policy area you care about, that’s a really lousy way of getting information.” Content customized and on-demandThe other way that Pro tries to help readers cut to the chase is by letting them customize their newsfeeds. So in addition to subscribing to basic alerts, briefings, coverage from specific reporters, and other updates in policy areas of interest, readers can tag up to 25 terms that matter to them. That could be the name of a senator, a particular piece of legislation, or just about anything at all, really. Check it out:

“Any time that we write about your member of Congress, your agency, your company, your client, that’s instantly sent in full email text to your BlackBerry,” VandeHei said. It may sound simple, but VandeHei calls what Politico Pro is doing “arguably the most important business innovation and arguably journalistic innovation” since Politico’s core site launched five years ago. “The reason I say that is it now gives us two different solid revenue streams, which gives us two different ways to fund really aggressive journalism,” VandeHei said. (Politico won its first Pulitzer Prize yesterday.) While the Pro reporters are grouped in a different area of the building than the other Politico reporters, VandeHei says Pro is ultimately a “descriptive term” and, “at the end of the day, it’s one newsroom.” Pro’s top editor Grieve also says that he’s hoping to foster more cross-pollination among reporters going forward. Already, there’s overlap. Pro reporters’ bylines are often on the core Politico site, and one Pro reporter recently hit the campaign trail with Mitt Romney when the core Politico team needed a break, Grieve says. “As we grow Pro, I think you’re going to see much more of that — much more crossing over and blending and people moving around the newsroom in creative and maybe surprising ways,” Grieve says. The other surprise will be what verticals Pro rolls out next. Executives won’t say which areas they’re exploring, but King says there are clues on the core site. “If you think about the way we have launched Pro products in the past, we’ve always launched around where we have done coverage,” King says. “For a hint on policy areas where we may be able to, over time, lend some insight from a Pro perspective, take a look at policy pages where we’ve covered everything from transportation to finance to defense. Those and more would be potential areas for future verticals.” The good news for those who can’t afford the pricey premium service — and for those who care about quality journalism in general — is that Pro’s growth directly affects what the core Politico team is able to cover. “If Pro didn’t exist, if there weren’t a base of readers who were interested in paying for the kind of highly detailed coverage Pro provides, it would be a limitaiton on the way Politico as a whole could cover this stuff — we might have one energy reporter, one technology reporter, one healthcare reporter,” Grieve said. “So when SOPA comes to the fore, when the contraception fight comes to the fore, when gas prices are the thing everyone’s talking about in Washington, there’s kind of an overwhelming force of manpower, expertise, knowledge, and insight that we can bring to bear for Pro readers and regular Politico readers that we just wouldn’t be able to do otherwise. It works from an editorial standpoint and works from a business standpoint. And if it doesn’t do both of those things, then it’s not going to happen.” Photo of the U.S. Capitol Rotunda by ctj71081 used under a Creative Commons license. |

| The New York Times’ Well blog gets more vertical with a redesign Posted: 17 Apr 2012 06:00 AM PDT

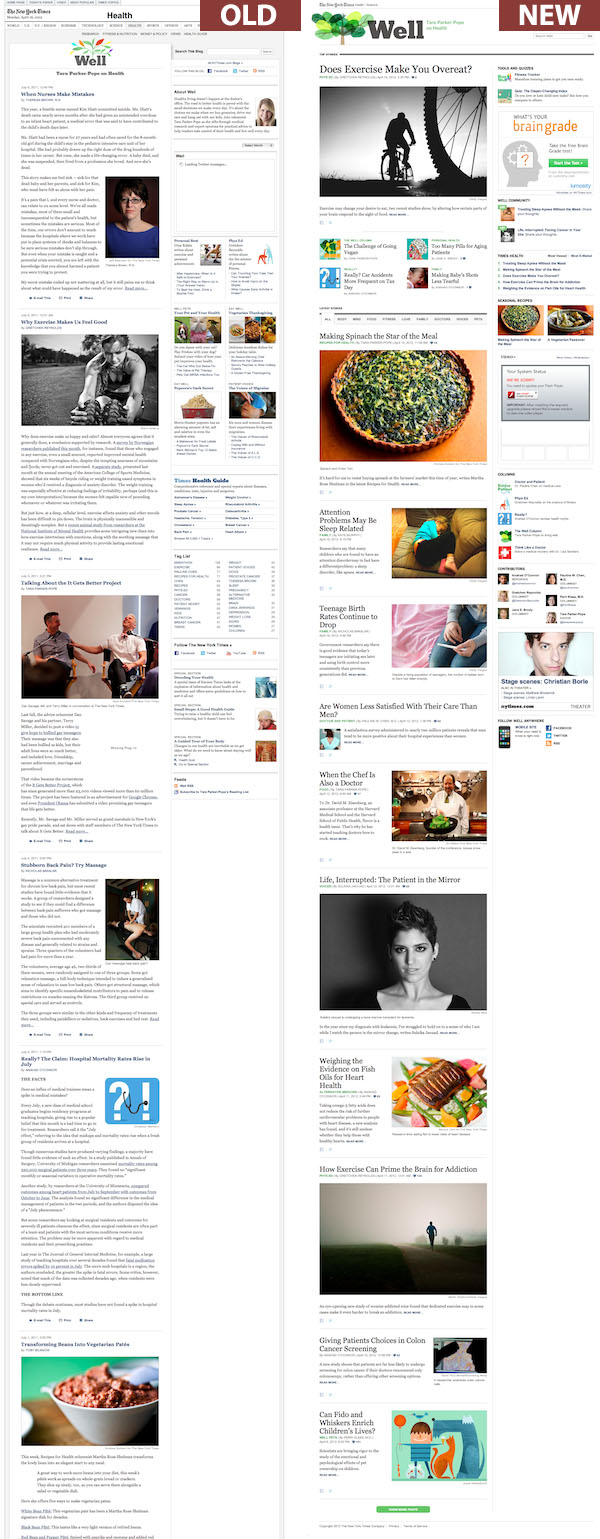

Well’s new look makes it look more like an independent website than another Times blog that might get linked from the nytimes.com front page now and then. Along with a single top story, the design promotes four editor-selected stories up high, pushes comment-heavy posts in the sidebar (“Well Community”), pushes tools, quizzes, and recipes up high, and lets readers slice Well’s content by subtopics (Body, Mind, Food, Fitness, and so on). Most stories get bigger and bolder art than the old design allowed; text excerpts are shorter, allowing more stories per vertical inch. Twitter and Facebook sharing tools are prominent on each post, even on the front page. Like Bits and DealBook, Well’s new look and feel is more reminiscent of what we associate with a blog and not a topic section of a newspaper website. As with Bits, The New York Times logo is shrunken to a mere 123 pixels wide, greyed in the upper left corner; the Well logo gets the big, 540-pixel-wide play. Along with the new look, Well is getting additional resources. Aside from Parker-Pope, Times writer Anahad O’Connor will join Well as a full-time reporter, and the site will still have writing from other Times contributors and staffers Jane Brody and Gretchen Reynolds. The transformation of Well has been in the works for several months and was first announced by James Follo, the Times chief financial officer, during an earnings call in February, where he said the company’s digital strategy called for expanding “some current content to drive increased engagement levels and additional points of access and create some entirely new homes for content.” Well, with its inclusive view on health including fitness, medical care, dieting and more, seems like a logical choice for the Times to try to build off their existing work to grow a new audience. It’s a topic area that has the ability to develop a following as well as attract advertisers; it’s been a pageview standout at the Times for years, with Well stories regularly hitting the most-emailed list.

When I spoke with Ian Adelman, director of digital design for the Times, he said it was important for Well to develop its own identity independent of the Times while still being associated with the paper. “That balance between giving room for that specific content to breath, exist, and surface more and maintaining a consistent presentation of the Times a is a little tricky,” Adelman said. That’s why Well, like Dealbook and Bits, has what you might call “light branding” from the New York Times, and why the navigation bar and other visual cues found on the rest of NYTimes.com are mostly missing. It’s also why there’s more elbow room on the page, on the Well home as well as story pages, giving art, multimedia, or discussion from readers a its own prominence. Adelman said the design is informed by editorial needs and doesn’t follow the templates you find on the rest of the site. For sites like NYTimes.com, those common templates are useful because of the sheer volume of information that moves across their pages each day. But the newer microsites within the Times architecture require more freedom, Adelman said. “When an entity is contained within the bigger shell of The New York Times, there’s a little less room for things that are unique to that content environment to surface and breath in ways that make sense,” he said. What’s unique to Well is that the content may be more disconnected to the day-to-day news cycle than Dealbook or Bits, where analysis and essays are intermixed with daily reporting. Well has seasonal recipes, fitness tools, and health quizzes, the type of material that can easily be tied into a news cycle and trends. But it also has stories with a long shelf life that can draw eyeballs over extended periods of time. (A piece on what works when trying to lose weight is guaranteed Googlebait for years to come.) Adelman said they redesigned the site with that in mind. “There are a number of new features that will be added — things that are not so much about news, but about the Well experience and creating a platform for people to get that and stick around longer,” he said. It’s likely Well is not the last section from NYTimes.com to be turned into its own mini empire. As the Times continues to work on its digital subscription framework, the incentives are stronger than ever to create dedicated audiences who want to keep coming back to a part of the site. The Times has a long history here: It was Abe Rosenthal back in the 1970s who expanded the print paper by adding so-called “soft sections” — Weekend, Sports Monday, Living, Home, and the like — that would appeal to specific niche audiences. That strategy, despite initial misgivings, has made the Times a lot of money over the years. So while building verticals online may be associated more with the Huffington Post, Gawker Media, or Vox Media than with any newspaper, the Times realizes the need to structure appealing containers for specific kinds of content. For the developers and designers at the Times that translates into more experimenting with how the company presents its journalism, Adleman said. “We’ll continue to evolve how we provide really great experiences for readers and finding new and better ways to incorporate more interesting materials into the story experience,” he said. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

What you might call the verticalization of The New York Times continues today with the

What you might call the verticalization of The New York Times continues today with the