Nieman Journalism Lab |

- Is the AP suing an aggregator or a search engine in the Meltwater case?

- In New Haven, a crisis of confidence over user comments

- Looking to Europe for news-industry innovation, Part 3: The Swiss “mikrozeitung” small community news model

| Is the AP suing an aggregator or a search engine in the Meltwater case? Posted: 15 Feb 2012 11:30 AM PST

The Associated Press is heading into court to defend its copyright, but its leaders swear they’re not on a crusade against aggregators. How the case evolves could pivot on how a court considers the site AP is suing — as a news clipping service or as a search engine. Tuesday morning, the AP filed suit against Meltwater, a news-monitoring service that delivers stories to clients for a fee. In the suit, the AP alleges Meltwater used their content verbatim, without a license, for their own profit. It’s a copyright case, with Meltwater accused of stealing content and customers from the AP, as well as “hot news” misappropriation. According to the company’s website, Meltwater offers a suite of media monitoring and aggregation products for businesses, including alerts and newsletters. Meltwater says it gathers information from more than 160,000 news sources, and it explicitly states: “Meltwater News is mindful of all copyright laws and regulations, making sure that all reports produced using our solutions adhere to these standards.” (Meltwater is facing other copyright issues across the pond. In a strange coincidence, Meltwater also received a ruling Tuesday from the U.K.’s Copyright Tribunal directing the company to pay a licensing fee to the British Newspaper Licensing Association.) In a statement released Tuesday afternoon, Meltwater said it complies with U.S. copyright law as it pertains to search engines: “Meltwater respects copyright and operates a complementary service that directs users to publisher websites, just like any search engine.” That last bit is one of the key issues here. Is Meltwater is a modern-day clip service, descended from its print-based predecessors, or is it a search-like product that delivers information in snippets? Andy Sellars, a staff attorney at Harvard’s Citizen Media Law Project, told me that distinction is important because courts have applied the fair use doctrine in different ways for the two. “If you characterize yourself as a news-clipping service, you find yourself in a whole cluster of cases that have not found fair use,” Sellars told me. “But if you characterize yourself as a search engine, you find yourself in a cluster of cases that have found fair use.” Search engines like Google inevitably create copies of publishers’ copyrighted content as part of their work, but courts have typically found they pass the fair use test. That’s likely why Meltwater is talking about itself in the terms of a search engine that crawls an extensive list of sources and offers up content on demand to clients. If all Meltwater is doing is providing a short blurb from a story and link, then they could be in the clear, Sellars said. But in the complaint the AP points out that unlike free aggregators, Meltrock is operating in a closed system that customers can only access by paying a fee. The company’s tools for customers are built specifically to replace the need for the AP, the complaint argues:

But the AP went a step further than a copyright-infringement suit by adding hot news misappropriation into the mix, saying Meltwater is free-riding on the AP’s “significant investments in gathering and reporting accurate, timely news, including breaking news.” Hot news, lest we forget the Fly on the Wall case, says publishers in some cases may have a limited monopoly over news they’ve reported (or put some blood and sweat into). But Sellars says AP is muddling its hot news claim by injecting arguments of the financial consequences of Meltwater’s use of unlicensed AP content. “To what extent there is a hot news claim in there, it’s hard to see whether that is the main thrust,” he said. “The copyright case is much more substantive.” The AP has not been shy about its desire to protect its content from free-riders, whether they are aggregation sites or individual bloggers. But AP went out of its way to note it is picking its battles carefully, calling Meltwater “not a typical news aggregator” and stating it does not “in any way seek to restrict linking or challenge the right to provide headlines and links to AP articles.” From the complaint:

There’s some tightrope walking there, and it seems of a piece with the strategy that’s been outlined by NewsRight, the content-tracking and licensing system endorsed (and invested in) by 29 news outlets, including the AP. The company claims it is more of a copyright tracker than a Righthaven-style litigator, with an emphasis on using software to measure the use of content across more than 16,000 websites. That includes a revised version of the AP’s Beacon, a subtle piece of JavaScript that is included in syndicated feeds from the cooperative. In an interview with us in January, NewsRight president David Westin noted the company’s stance “doesn’t mean down the road there won’t be litigation. I hope there’s not. Some people may decide to sue, and we can support that with the data we gather, the information we gather. But…those are very expensive, cumbersome, time-consuming processes.” In the suit, Meltwater is accused of periodically removing information that could ID the AP as the copyright holder on articles. Stripping out copyright management information is banned by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act; even though it’s usually associated with material like movies and music, it can also applies to text-based news. Sellars said the case could be a test as to whether fair use can be applied to a person or company that removes copyright information. “Even if you’re using fair use, if you circumvent encryption, you could be held liable,” he said. Needle-in-a-haystack photo by Tomas Buchtele used under a Creative Commons license. |

| In New Haven, a crisis of confidence over user comments Posted: 15 Feb 2012 09:00 AM PST

If Paul Bass can no longer handle online comments, has public participation reached the end of the line? Like many observers, I was stunned last week when I learned that the New Haven Independent, a nonprofit local news site that Bass launched in 2005, had suspended comments. “The tone of commenting on the Independent…seems to have skidded to the nasty edges and run off the rails,” Bass wrote on Feb. 7. “We’re responsible for reading, vetting, and posting all comments on the site. We’ve failed in our responsibility to keep the discussion on track.” What made Bass’s decision especially disconcerting is that the Independent enjoyed a well-deserved reputation for the way it managed comments, building a genuine community around its journalism. I was an unabashed admirer, and a book I’m writing about the Independent and other local news sites lavishes considerable attention on how Bass got it right. Bass and his small staff spent many hours each week screening comments to make sure that racist, hateful remarks did not find their way onto the site. That stood in contrast to the local daily paper, the Journal Register Co.’s New Haven Register, whose anything-goes policy was often cited to me by members of the African-American community in explaining why they’d stopped reading the paper. “He [Bass] just doesn’t allow people to say anything and post anything. And I think that really speaks volumes to his character,” Shafiq Abdussabur, a New Haven police officer and community activist, told me in a 2010 interview. “And in return it speaks volumes to the reputation and character of the newspaper. Because let me tell you, one bad racial comment that you stick in a paper like that, you can lose your whole urban readership.” Ironically, it is now the Register — part of John Paton’s “Digital First” initiative — that is following the path set by Bass. Last August, the Register brought in a young, progressive editor, Matt DeRienzo, previously known for the Open Newsroom Project he ran as publisher of the Register Citizen of Torrington, Conn. And several months after DeRienzo’s arrival in New Haven, the Register finally began screening comments before they were posted. It was DeRienzo, too, who wrote perhaps the most heartfelt plea for Bass to restore comments to the Independent. “How can the community be part of your journalism if you don’t even allow them to comment on what you do?” DeRienzo asked on his blog, Connecticut Newsroom. But if the Independent is no longer accepting comments, the conversation about comments continues. In an entirely predictable development, people are talking on other sites about Bass’ cone of silence — with the Independent’s active encouragement, as the Independent has linked to several blogs and news sites so that its former commenters can join in. Bass himself has posted several responses. As of Tuesday evening, 52 comments about the Independent had been posted to DeRienzo’s blog; 38 to a post written by Ben Berkowitz, a co-founder of the New Haven-based civic-media project SeeClickFix; and 28 to my own blog, Media Nation. Among my commenters: Bass and DeRienzo, as well as a longtime critic of Bass’ and a former New Haven alderman. Earlier this week, I sent Bass an email asking him whether he had deliberately driven the conversation to other sites to help him figure out his next move. “Yes, following the comments elsewhere both to help inform what we should do — and to respond to people with questions or critiques,” he replied. He estimated that 85 percent of people posting publicly want the Independent’s comments restored, whereas 85 percent of those sending him emails support his decision to shut them down. “Those of us who wrestled with posting comments and some really abusive and relentless people all day and night are feeling much happier since the comments stopped,” Bass continued. “Our moods have brightened. We are nicer people to be around.” So should the comments resume? I think they have to — they’re too integral a part of the Independent’s identity. Civic engagement has been on the wane for years, and it’s not enough for journalism merely to serve the public. As I wrote for The Guardian in 2009, news organizations need to recreate the very idea of a public by encouraging a sense of involvement and participation. At least until recently, the Independent did a remarkable job of doing just that. But clearly something changed. Unlike another news-site publisher whose comments policy I respect, Howard Owens of The Batavian, Bass has always allowed people to post anonymously or pseudonymously. Bass argues that the police officers, teachers, and other city stakeholders who are among his most dedicated commenters would never dare post if they had to reveal their identities. So a real-names policy is out, as is Facebook authentication. But there are other steps Bass could take to restore civility while maintaining his sanity. Here’s one idea I discussed with him: require users to register under their real names before they comment. Yes, they’d still be allowed to post anonymously, but they’d know Bass knows who they are, which can have a calming effect. Moreover, registration would make it easier to ban abusive commenters, saving Bass and his staff the bother of having to screen posts from known troublemakers. Some two decades ago, when we started down the online-news road, I think many of us were both idealistic and unrealistic about what the “people formerly known as the audience” (to use Dan Gillmor‘s phrase) could contribute. The answer, I think, is not to walk away from the conversation, but to figure out ways of managing it better. I thought Bass had struck the right balance. But what worked in 2005, or 2009, may no longer be enough for 2012. That requires a new way forward, not a retreat. I hope Bass doesn’t give up on his community. If he does, I’m afraid it may choose to give up on him. Dan Kennedy is an assistant professor of journalism at Northeastern University and a panelist on “Beat the Press,” a weekly media program on WGBH-TV (Channel 2). His blog, Media Nation, is online at www.dankennedy.net. |

| Posted: 15 Feb 2012 08:00 AM PST

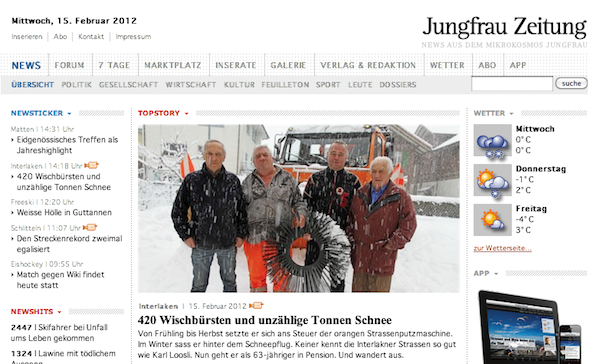

In the first two parts of this series, we’ve focused on Schibsted’s classifieds and online services innovations and on Sanoma’s pioneering digital circulation initiatives. Today we look at a small community news model. That’s hugely important. Much of the news world focuses on the twists and turns of national/global news players and of largely devastated metros. But smaller community papers deliver much of the news to readers in the U.S. and across the world. Gossweiler Media, for that reason, offers an intriguing model, built on straightforward arithmetic. It’s a family story, as newspapers were a family story for centuries. Rolled up and corporatized in the 20th century by chains, we’re now seeing the early sprouts of individuals and families once again expressing ownership interest. If that movement continues to pick up steam, examples such as this small Swiss news operation are instructive. Urs Gossweiler, CEO of Gossweiler Media AG, is the grandson of a newspaper founder. Running the company out of Brienz, a large hamlet in Switzerland, Gossweiler’s newspaper/news site Jungfrau Zeitung has become well known in European newspaper circles. Their hallmark: focusing on news creation and community service first, divorcing the news business from the means of distribution. Their model: low costs, high margins — a model that Gossweiler is now franchising. I spoke with him at last fall’s WAN-IFRA World Newspaper Congress in Vienna. He spoke on an “Opportunities” panel there, one of his many speaking engagement spreading the gospel of news-without-paper throughout Europe. It’s not that Gossweiler doesn’t like paper; he just doesn’t feel wedded to it. Jungfrau Zeitung publishes two papers a week — on Tuesday and Friday — but it has long supported non-print products, and now offers a set of robust mobile apps in addition to its thoroughly updated website. Gossweiler was multimedia before it was called multimedia. In 1983, at age 14, he founded a youth-radio outfit, purposely taking a twist in his family’s saga. “My father was a capitalist, and I was a communist,” he says with a smile.

“My father bought the first Macintosh computer. It was like taking down the Berlin Wall.” Today, Gossweiler Media has grown from its early days as a print publisher of the Brienzer. It publishes its “mikrozeitung”, or micro-newspaper, twice a week in print — and throughout the day online. Jungrau Zeitung serves an area of about 45,000 people — small enough for people to feel a sense of real community, but large enough to create a market. (Curiously, that’s around the size of many of Patch’s markets. As Patch head Warren Webster has noted, his company can create lots of local news at a fraction of traditional seven-day print costs.) The mikrozeitung example, then, gives traditional businesses a path of thinking and acting differently about their own transitions. Thinking differently includes everything from press ownership to ad selling to staff responsibilities. — Jungfrau Zeitung is profoundly local. “We have no local section,” says Gossweiller. “We are purely local, with separate sections for politics, sports, arts and classifieds.” Gossweiler Media makes this point cleanly on its own site, showing a hierarchy from the global International Herald Tribune to the national Neue Zürcher Zeitung to the local Jungfrau Zeitung. At WAN-IFRA last fall, Gossweiler showed a photo of Barack Obama and noted: “This man has never been in our newspaper.” He switched to a picture of the local mayor: “This man is always in the paper.” The message: Use others for the rest of the world; for local, depend on us.

— Most importantly, it sells advertising in a totally integrated way. When advertisers buy ads, they’re forced into a combination of print, online and, newly, mobile inventory. That inventory is allocated by formula. “It used to be they’d say ‘we’re buying print, and we’ll take online.’ Now they say, we’re buying online, and we’ll take print,” says Gossweiler. While its print circulation (now around 8,800) is in decline, its overall reach has grown, now including 57,000 monthly unique visitors. — To that end, the company sold its presses way back in 1994 and began outsourcing that work. “A lot of publishers are not publishers,” he told me. “They are printers.” Given the new economics of the business, Gossweiler says he earns more than a 30 percent profit — a number that’s led him to begin franchising the business to other communities. Where smaller newspapers were bought up by the Gannetts of the world in the late 20th century, Gossweiler is trying to spread his model through a different model. The company launched its first licensee last year, in a neighboring town, and the company is now actively pitching other potential publishers in Austria and Germany. For $250,000 a year, franchisees receive a package of services, ranging from marketing to its self-built technology platform named G-OS. The first licensee is a consortium of 40 local owners, publishing Obwalden und Nidzalden Zeitung. No single investor owns more than 8 percent of the company, making it itself an intriguing model of what ownership of local “newspapering” could be about in our hybrid era. Behind the scenes, the organization of Gossweiller Media parallels that of big news organizations that have won headlines transforming themselves. Each micro-newspaper sports a staff of 15: Eight editors, four ad sales people and three producers. The company recently won a SwissCom Business Award for services, and that award noted as much about how slickly multimedia journalism is produced, as how it is distributed:

All Gossweiler’s journalists produce video in this multimedia landscape. The current production pace is two per day for the site, or about 14 video segments a week. Jungrau Zeitung’s iPad app won Apple approval in November; it builds on mobile-optimized smartphone products. Gossweiler says building out in HTML5 is a next priority. The company also produces a weekly 12-minute TV show — the Funky Kitchen Club — which is both webcast and broadcast. Business and revenue models The microzeitung business model appears fairly straightforward. As offered to potential franchisees, each local media site, serving a population of about 45,000, would run an annual budget of 3 million Swiss francs. (A Swiss franc is worth about US$1.08.) Here’s the breakdown: Jungfrau Zeitung charges 165 Swiss francs a year for a one-year, all-access subscription. Gossweiler doesn’t charge separately for digital access, believing that “people won’t pay for news because it’s nothing you want to collect.” Key metrics

Takeaways for publishers:

Urs Gossweiler photo by Beat Rechsteiner. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |