Nieman Journalism Lab

|

- This Week in Review: Google and the social search wars, and the Post’s in-house innovation critic

- Craig Newmark: Fact-checking should be part of how news organizations earn trust

- Boston.com adds tweets to news feed for Your Town sites

|

Posted: 13 Jan 2012 08:30 AM PST

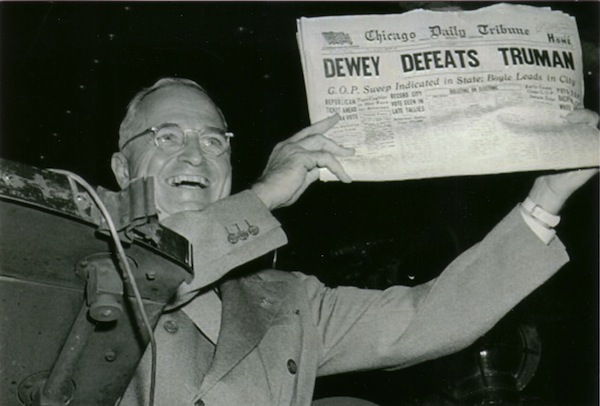

Social search and competition: Google made a major move toward unifying search and social networks (particularly its own) this week by fusing Google+ into its search and deepening its search personalization based on social information. It’s a significant development with a lot of different angles, so I’ll try to hit all of them as understandably as I can. As usual, Search Engine Land’s Danny Sullivan put together the best basic guide to the changes, with plenty of visual examples and some brief thoughts on many of the issues I’ll cover here. TechCrunch’s Jason Kincaid explained that while these changes may seem incremental now, they’re foreshadowing Google’s eventual goal to become “a search engine for all of your stuff.” PaidContent’s Jeff Roberts liked the form and functionality of the new search, but said it still needs a critical mass of Google+ activity to become truly useful, while GigaOM’s Janko Roettgers said its keys will be photos and celebrities. ReadWriteWeb’s Jon Mitchell was impressed by the non-evilness of it, particularly the ability to turn it off. Farhad Manjoo of Slate said Google’s reliance on social information is breaking what was a good search engine. Of course, the move was also quite obviously a shot in the war between Google and Facebook (and Twitter, as we’ll see later): As Ars Technica’s Sean Gallagher noted, Google wants to one-up Facebook’s growing social search and keep some of its own search traffic out of Facebook. Ben Parr said Facebook doesn’t need to worry, though Google has set up Google+ as the alternative if Facebook shoots itself in the foot. But turning a supposedly neutral search engine into a competitive weapon didn’t go over well with a lot of observers. The Atlantic’s Alexis Madrigal saw a conflict between Google’s original mission (organizing the world’s information) and its new social mission, and Danny Sullivan said Google is putting score-settling above relevance. Several others sounded similar alarms: Mathew Ingram of GigaOM said users are becoming collateral damage in the war between the social networks, and web veteran John Battelle argued that the war was bad for Google, Facebook, and all of us on the web. “The unwillingness of Facebook and Google to share a public commons when it comes to the intersection of search and social is corrosive to the connective tissue of our shared culture,” he wrote. For others, the changes even called up the specter of antitrust violations. MG Siegler said he doesn’t mind Google’s search (near-) monopoly, but when it starts using that monopoly to push its other products, that’s when it turns into a legal problem. Danny Sullivan laid out some of the areas of dispute in a possible antitrust case and urged Google to more fully integrate its competitors into search. Twitter was the first competitor to voice its displeasure publicly, releasing a statement arguing that deprioritizing Twitter damages real-time search. (TechCrunch has the statement and some valuable context.) Google responded by essentially saying, “Hey, you dumped us, buddy,” and its executive chairman, Eric Schmidt, told Search Engine Land they’d be willing to negotiate with Twitter and Facebook. Finally, some brief journalistic implications: Poynter’s Jeff Sonderman said this means SEO’s value is waning for news organizations, being replaced by the growing importance of building strong social followings and making content easy to share, and Mathew Ingram echoed that idea. Daniel Victor of ProPublica had some wise thoughts on the meaning of stronger search for social networks, concluding that “the key is creating strategies that don't depend on specific tools. Don't plan for more followers and retweets; plan for creating incentives that will gather the most significant contributions possible from non-staffers.”  Innovation and its discontents: Washington Post ombudsman Patrick Pexton inducing a bit of eye-rolling among digital media folks this week with a column arguing that the paper is “innovating too fast” by overwhelming readers and exhausting employees with a myriad of initiatives that lack a coherent overall strategy. J-prof Jay Rosen followed up with a revealing chat with Pexton that helps push the discussion outside of the realm of stereotypes: Pexton isn’t reflexively defending the status quo (though he remains largely print-centric), but thinks there are simply too many projects being undertaken without an overarching philosophy about how or why things should be done. Pexton got plenty of push-back, not least from the Post’s own top digital editor, Raju Narisetti, who responded by essentially saying, in Rosen’s paraphrase, “This is the way it's going to be and has to be, if the Post is to survive and thrive. It may well be exhausting but there is no alternative.” GigaOM’s Mathew Ingram said he was just about to praise the Post for its bold experimentation, and the Guardian’s Martin Belam argued that Pexton is actually critiquing newness, rather than innovation. J-prof Alfred Hermida argued — as Pexton himself seemed to in his chat with Rosen — that the issue is not about how fast or slow innovation is undertaken, but whether that innovation is done in a way that’s good or bad for journalism. Former Sacramento Bee editor Melanie Sill responded that many newspapers remain stuck in 20th-century formulas, blinding them to the fact that what they consider revolutionary change is only a minor, outmoded shift. She noted that all the former top editors she’s talked to have had the same regret: that they hadn’t pushed harder for change. And Free Press’ Josh Stearns pointed out that we should expect the path toward that change to be an easy one.  ‘Truth vigilantes’ and objectivity: Pexton wasn’t the only ombudsman this week to be put on the defensive after a widely derided column: New York Times public editor Arthur Brisbane drew plenty of criticism yesterday when he asked whether Times reporters should call out officials’ untruths in their stories — or, as he put it, act as a “truth vigilante.” Much of the initial reaction was a variation of, “How is this even a question?” Brisbane told Romenesko that he wasn’t asking whether the Times should fact-check statements and print the truth, but whether reporters should “always rebut dubious facts in the body of the stories they are writing.” He reiterated this in a follow-up, in which he also printed a response by Times executive editor Jill Abramson saying the Times does this all the time. Her point was echoed by former Times executive editor Bill Keller and PolitiFact editor Bill Adair, and while he called the initial question “stupid,” Reuters’ Jack Shafer pointed out that Brisbane isn’t opposed to skepticism and fact-checking. The American Journalism Review’s Rem Rieder enthusiastically offered a case for a more rigorous fact-checking role for the press, as did the Online Journalism Review’s Robert Niles (though his enthusiasm was with tongue lodged in cheek). The Atlantic’s Adam Clark Estes used the episode as an opportunity to explain how deeply objectivity is ingrained in the mindset of the American press, pointing to the “view from nowhere” concept explicated by j-prof Jay Rosen. Rosen also wrote about the issue himself, arguing that objectivity’s view from nowhere has surpassed truthtelling as a priority among the press.  How useful is the political press?: The U.S. presidential primary season is usually also peak political-journalism-bashing season, but there were a couple of pieces that stood out this week for those interested in the future of that field. The Washington Post’s Dana Milbank mocked the particular pointlessness of this campaign’s reporting, describing scenes of reporters vastly outnumbering locals at campaign events and remarking, “if editors knew how little journalism occurs on the campaign trail, they would never pay our expenses.” The New Yorker’s John Cassidy defended the political press against the heat it’s been taking, arguing that it still produces strong investigative and long-form reporting on important issues, and that the speed of the new news cycle allows it to correct itself quickly. He blamed many of its perceived failings not on the journalists themselves, but on the public that’s consuming their work. The Boston Phoenix reported on the decline of local newspapers’ campaign coverage and wondered if political blogs and websites could pick up the slack, while the Lab’s Justin Ellis looked at why news orgs love partnering up during campaign season, focusing specifically on the newly announced NBC News-Newsweek/Daily Beast arrangement.  A unique paywall model: The many American, British, and Canadian publishers implementing or considering paywalls might marvel at the paid-content success of Piano Media, but they can’t hope to emulate it: A year after gaining the cooperation of each of Slovakia’s major news publishers for a unified paywall there, the company is expanding the concept to Slovenia. As paidContent noted, Piano is hoping to sign up 1% of Slovenia’s Internet-using population, and the Lab’s Andrew Phelps reported that the company is planning to bring national paywalls to five European nations by the end of the year. As Piano’s CEO told Phelps, the primary barrier to subscription has not been economic, but philosophical, especially for commenting. Elsewhere in paywalls, media consultant Frederic Filloux looked at what’s making The New York Times’ strategy work so far — unique content, a porous paywall that allows it to maintain high traffic numbers and visibility, and cooperation with Apple — and analyst Ken Doctor wondered whether all-access subscriptions across multiple devices and publications within a company could be a key to paid content this year. — One item I forgot to note from late last week: The AP and a group of 28 other news organizations have launched NewsRight, a system to help news orgs license their content to online aggregators. Poynter’s Rick Edmonds offered a detailed analysis, but GigaOM’s Mathew Ingram was skeptical. — The online commenting service Disqus released some of its internal research showing that pseudonymous commenters tend to leave more and higher-quality comments than their real-name counterparts. GigaOM’s Mathew Ingram used the data to argue that a lack of real names isn’t nearly as bad as its critics say. — No real news in SOPA this week, but the text of Cory Doctorow’s lecture last month on SOPA and the dangers of copyright regulation has been posted. It’s long, but worth a read. — Finally, three fantastic practical posts on how to practice digital journalism, from big-picture to small-grain: Howard Owens of the Batavian’s list of things journalists can do to reinvent journalism, Melanie Sill at Poynter on how to begin doing open journalism, and Steve Buttry of the Journal Register Co. on approaching statehouse coverage from a digital-first perspective. Photo by SpeakerBoehner used under a Creative Commons license. |

|

Posted: 13 Jan 2012 08:00 AM PST

Okay, I’m not in the news business, and I’m not going to tell anyone how to do their job. However, it’d be good to have news reporting that I could trust again, and there’s evidence that fact checking is an idea whose time has come. This results from smart people making smart observations, at two recent conferences about fact checking, one run by Jeff Jarvis at CUNY (with me involved) and a more recent one at the New America Foundation. I’ve surfaced the issue further by carefully circulating a prior version of this paper. Restoring trust to the new business via fact checking might be an idea whose time has come. It won’t be easy, but we need to try. Fact checking is difficult, time consuming, and expensive, and it’s difficult to make that work in current newsrooms. There are Wall Street-required profit margins, and the intensity of the 24×7 news cycle. The lack of fact checking becomes obvious even to guys like me who aren’t real smart. It’s worse when, say, a cable news reporter interviews a public figure, and that figure openly lies, and the reporter is visibly conflicted but can’t challenge the public figure. That’s what Jon Stewart calls the “CNN leaves it there” problem, which may have become the norm. When such interviews are run again and quoted, that reinforces the lie, and that’s real bad for the country. Turns out that The New York Times just asked “Should The Times Be a Truth Vigilante?” That’s a much more pointed version of the question I’ve previously posed. The comments are overwhelming, like “isn’t that what journalists do?” and the more succinct “duh.” For sure, there are news professionals trying to address the problem, like the folks at Politifact and Factcheck.org. We also see great potential at American Public Media’s Public Insight Network; with training in fact checking, their engaged specialist citizens might become a very effective citizen fact-checking network. (This list is far from complete.) My guess is that we’ll be seeing networks of networks of fact checkers come into being. They’ll provide easily available results using multiple tools like the truth-goggles effort coming from MIT, or maybe simple search tools that can be used in TV interviews in real time. Seems like a number of people in journalism have similar views. Here’s Craig Silverman from Poynter reporting recent conferences. Silverman and Ethan Zuckerman had a really interesting discussion regarding the consequences of deception: That brings me to the final interesting discussion point: the idea of consequences. Can fact checking be a deterrent to, or punishment for, lying to the public?I’m an optimist, and hope that an apparent surge of interest in fact checking is real. Folks, including myself, have been pushing the return of fact checking for some months now, and recently it’s become a more prominent issue in the election. Again, this is really difficult, but necessary. I feel that the news outlets making a strong effort to fact-check will be acting in good faith and trustworthy, and profitable. However, this seems like a good way to start restoring trust to the news business.

Craig Newmark is the founder of craigslist, the network of classified ad sites, and craigconnects, an organization to connect and protect organizations doing good in the world.

|

|

Posted: 13 Jan 2012 07:00 AM PST

The Boston Globe is quietly testing a redesign of its Your Town product on Boston.com to give the locally focused sites a more engaged, real-time feel. And “real-time feel” is short for a blog-like, Twitter-like stream of stories and information. Your Town is a network of 50 sites dedicated to local news in the towns surrounding Boston proper, places like Cambridge (home of the Lab), Quincy, Salem, and Brookline. It’s the Brookline site where the Globe is testing out a new two column look — change from the three-column layout before — with a main well dedicated to aggregating local news and a left rail that’s home to ads, local services, an events calendar and links for SeeClickFix. It’s a clean, open kind of design, which, on first glance is very bloggy and a little Twitter-esque. Jim Bodor, director of product development for Boston.com, said that’s exactly the idea. Over email Bodor told me they wanted to create a “dashboard for a reader’s community.” “The design changes are aimed at giving the Your Town home pages a more social and real-time feel,” he said. The Your Town sites, which are staffed by an editor and a writer, are by and large aggregators, combining regional town coverage from the Globe, but also incorporating local blogs and other community news sites (like the blog of the local police department). But the new look also aggregates individual tweets hand-plucked from locals on Twitter, displaying them inline with other news in the feed. A tweet earns the same visual rank as a Globe story, each its own solo news item. It’s common for news sites to include Twitter widgets displaying their own tweets or those from trusted sources, but it’s rare to see tweets themselves — particularly non-staff-produced tweets — displayed as a unit of news. Bodor said what’s happening on Twitter is part of the broader news discussion in a community, one that a segment of readers already knows about. This amplifies that to a larger audience and creates a richer site, he said. “Before we launched the new site, we identified prominent tweeters in Brookline who we know tweet regularly about local topics, and are automatically incorporating those tweets into the stream,” he said. Employing Twitter makes for a good two-for-one opportunity. By sourcing and prominently featuring tweets from the community Your Town not only can add to the amount of content on sites but also extend a hand to readers and create a more engaged audience. That’s important because the Your Town sites are in a competitive local-news space that includes Patch sites as well as the Wicked Local network competing on school coverage, traffic and road updates, and sports from Pop Warner on up. And now with the recent split between Boston.com and BostonGlobe.com, readers, especially those in the ring around the bay, have a stark choice to make between free and paid, not just regional and local news. A redesign, and the inclusion of Twitter, while not exactly earth shattering moves, could help move readers in the direction of Boston.com and Your Town sites. It’s been three years since the Your Town sites launched and, aside from the usual town-by-town fluctuations, they maintain steady traffic. While not going into specifics, Bodor said Your Town “is driving significant, material traffic throughout Boston.com,” and is consistently among the 10 best performing parts of Boston.com. Since the Brookline site went live a few weeks ago, Bodor and his team have been monitoring readers responses as well as any bugs or issues that pop up. They’re calling the Brookline site a beta, but plan to rollout the same design scheme across the rest of the sites in the next few months. |