Nieman Journalism Lab |

- Image as interest: How the Pepper Spray Cop could change the trajectory of Occupy Wall Street

- Deadline approaching for international journalists to apply for a Nieman Fellowship

- From white paper to newspaper: Making academia more accessible to journalists

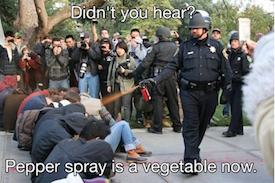

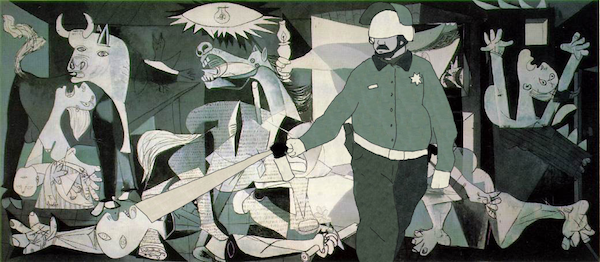

Posted: 21 Nov 2011 11:30 AM PST  In his Times column this morning, David Carr wonders about the future of the Occupy Wall Street movement and, specifically, its fate as an ongoing topic of mass-media conversation. “Occupy Wall Street left many all revved up with no place to go,” he writes. Which is a problem, traditional-press-coverage wise, because: “In addition to the 5 W's — who, what, when, where and why — the media are obsessed with a sixth: what's next? Occupy Wall Street, for all its appeal as a story, is very hard to roll forward.” That could be true (though “very hard,” of course, is quite different from “impossible”). And it could also be true that the features that may give Occupy, potentially, enduring power as a movement — its malleability, its permissiveness, its ability to act as an interface as well as an event — might also be the forces that, day to day, challenge its ability to convene attention. Particularly at the level of the mass culture.  It’s worth returning, for a moment, to the idea of trending topics algorithms, which reward discrete events over ongoing movements, favoring spikes over steadiness, effectively punishing trends that build, gradually, over time. (Which is to say: effectively punishing the notion of a “movement” itself.) This bias toward the spiky over the sticky is a defining feature, as well, of the daily workings of the traditional media (and of their great organizational mechanism, the Epiphanator): Occupy’s much-discussed lack of a singular identity has been not only kind of the whole point, but also, to some extent, the result of the way the movement has been mediated by a press that tends to reward newness over endurance. Occupy’s story — like all stories of ongoing political movements that are told by traditional producers of daily journalism — has been told episodically, in staccato rhythms that emphasize explosive ruptures in expectation. (“Expectation,” of course, being defined by the Epiphanator itself.) Occupy is, like so many other movements, subject to “the tyranny of recency.” It’s worth returning, for a moment, to the idea of trending topics algorithms, which reward discrete events over ongoing movements, favoring spikes over steadiness, effectively punishing trends that build, gradually, over time. (Which is to say: effectively punishing the notion of a “movement” itself.) This bias toward the spiky over the sticky is a defining feature, as well, of the daily workings of the traditional media (and of their great organizational mechanism, the Epiphanator): Occupy’s much-discussed lack of a singular identity has been not only kind of the whole point, but also, to some extent, the result of the way the movement has been mediated by a press that tends to reward newness over endurance. Occupy’s story — like all stories of ongoing political movements that are told by traditional producers of daily journalism — has been told episodically, in staccato rhythms that emphasize explosive ruptures in expectation. (“Expectation,” of course, being defined by the Epiphanator itself.) Occupy is, like so many other movements, subject to “the tyranny of recency.”  But that may well have just changed. This weekend, a series of photographs — images of a riot-gear-wearing cop shooting a group of students in the face with pepper spray — made their transition from journalistic documents to sources of outrage to, soon enough, Official Internet Meme. Perhaps the most iconic image (taken by UC Davis student Brian Nguyen, and shown above) isn’t explicitly political; instead, it captures a moment of violence and resistance in almost allegoric dimensions: the solidarity of the students versus the singularity of the cop in question, Lt. Pike; their steely resolve versus his sauntering nonchalance; the panic of the observers, gathered chorus-like and open-mouthed at the edges of the frame. The human figures here are layered, classified, distant from each other: cops, protestors, observers, each occupying distinct spaces — physical, psychical, moral — within the image’s landscape. As James Fallows put it, “You don’t have to idealize everything about them or the Occupy movement to recognize this as a moral drama that the protestors clearly won.” Exactly. The image — and its subsequent meme-ification — marked the moment when the Occupy movement expanded its purview: It moved beyond its concern with economic justice to espouse, simply, justice. It became as much about inequality as a kind of Platonic concern as it is about income inequality as a practical one. It became, in other words, something more than a political movement.  The image itself, I think — as a singular artifact that took different shapes — contributed to that transition, in large part because the photo’s narrative is built into its imagery. It depicts not just a scene, but a story. It requires of viewers very little background knowledge; even more significantly, it requires of them very few political convictions, save for the blanket assumption that justice, somehow, means fairness. The human drama the photo lays bare — the powerless being exploited by the powerful — has a universality that makes its particularities (geographical location, political context) all but irrelevant. There’s video of the scene, too, and it is horrific in its own way — but it’s the still image, so easily readable, so easily Photoshoppable, that’s become the overnight icon. It’s the image that offers, in trending topic terms, a spike — a rupture, an irregularity, a breach of normalcy. It’s the image that demands, in trending topic terms, attention. The image itself, I think — as a singular artifact that took different shapes — contributed to that transition, in large part because the photo’s narrative is built into its imagery. It depicts not just a scene, but a story. It requires of viewers very little background knowledge; even more significantly, it requires of them very few political convictions, save for the blanket assumption that justice, somehow, means fairness. The human drama the photo lays bare — the powerless being exploited by the powerful — has a universality that makes its particularities (geographical location, political context) all but irrelevant. There’s video of the scene, too, and it is horrific in its own way — but it’s the still image, so easily readable, so easily Photoshoppable, that’s become the overnight icon. It’s the image that offers, in trending topic terms, a spike — a rupture, an irregularity, a breach of normalcy. It’s the image that demands, in trending topic terms, attention. And it also demands participation. A key feature of the Epiphanator, the mechanism of press-mediated storytelling that defined our sense of the world for so long, is its impulse to organize time itself into discrete artifacts. Journalists tend to be obsessed with beginnings and, even more importantly, endings. This is how we make sense of things. What’s notable about the Lt. Pike image, though, is how dynamic its path has been — this despite the defining stillness of still photography — by way of the complementary filters of social media and human creativity.  The image of Pike (nom de meme: the Pepper Spray Cop) isn’t the first to reach a kind of iconic status when it comes to Occupy Wall Street. (It’s not even the first to involve pepper spray. See, for example, the horrific image of 84-year-old Dorli Rainey, her face dripping with burn-assuaging milk after being sprayed in Seattle.) But it is the first whose implicit narrative — one of struggle, one of outrage — offers viewers a kind of ethical, and tacitly emotional, participation in Occupy Wall Street. A moral drama that the protestors clearly won. Images, Susan Sontag argued, are “invitations” — “to deduction, speculation, fantasy.” They invite empathy, and, with it, investment. It remains to be seen whether Pepper Spray Cop, as a singular image and a collection of derivatives, will prove enduring in the way that previous iconic photos — Phan Thi Kim Phúc, Tank Man — have done. But Pepper Spray Cop, and his ad hoc iconography, is a telling case study for observing what happens when political images become, in the social setting of non-traditional media, de- and then re-politicized. And it will be interesting to see whether the image’s viral life will affect David Carr’s question of “what’s next” for Occupy Wall Street in the world of traditional media. “Just a week ago,” NPR noted this morning, “it was starting to seem like the Occupy movement might be running short of fuel.” But “now that movement seems to have fresh energy after a week of police crackdowns across the country.” Images by Brian Nguyen, Billy Galbreath, Kosso K, the Pepper Spraying Cop Tumblr, and Matt Uebel. |

Posted: 21 Nov 2011 11:00 AM PST  It’s fall here in Cambridge, which means it’s time again for journalists from around the world to be thinking about applying for a Nieman Fellowship. Niemans get to spend a year at Harvard, studying the subjects of their choice with the aim of making them better journalists at year’s end than they were at year’s start. Our next class of fellows, who’ll arrive in Cambridge next August and stay through May 2013, will be our 75th. Each Nieman class numbers between 20 and 30, roughly evenly split between American and international journalists. And — important note here — the deadline for international journalists to apply has moved up this year, to December 1. (It had been December 15 for some years. For Americans, the deadline is January 31.) There’s lots of information about the fellowships over at the main Nieman website, including details on eligibility, our specialized fellowships, and other details like how much we pay you, how your family can join the experience, and Nieman activities. You can read about the current class of fellows to get an idea who’s preceded you. You can apply entirely online — you’ll have to write a couple brief essays about what you’re like to accomplish, and we’ll need letters of recommendation and examples of your work. But it’s not an inordinately time-consuming process — international journalists still have plenty of time between now and Dec. 1 to get it done. Three quick notes:

|

Posted: 21 Nov 2011 07:30 AM PST  As an idea, “knowledge-based reporting” sounds pretty hard to disagree with. No-brainer, right? But Harvard Prof. Tom Patterson has argued that knowledge is woefully absent from most journalism today: Journalists are not trained to think first about how systematic knowledge might inform a news story. They look first to the scene of action and then to the statements of involved or interested parties. Typically, the question of whether a particular episode might have a fuller explanation is never asked. Stanford's Shanto Iyengar has concluded in his studies that news is overwhelmingly “episodic.” Events are usually reported in isolation.Of course, scholars aren’t producing daily stories on tight deadlines. Real knowledge-based reporting is hard. On some stories, the people most qualified to write them are probably your sources. So we journalists rely on interviews, past articles, and seemingly trustworthy material on the web and elsewhere. About 18 months ago, Patterson and others at Harvard’s Shorenstein Center set out to make knowledge more accessible. They created a website called Journalist’s Resource, a curated, searchable index of high-quality research papers on topics of interest to reporters. The site’s editors write up studies in a journalistic way, plucking out facts and narratives that can be woven into stories. Unlike most academic products, Journalist’s Resource is openly accessible, well-designed, and licensed under Creative Commons. And now, as the pace of 2012 election coverage quickens, Journalist’s Resource is preparing to debut a special political section. Alex Jones, director of the Shorenstein Center, said Journalist’s Resource is an endorsement of a different kind of journalism. “We don’t claim to have a corner on truth, but what we are trying to do is make the case that the best, most reliable insights…on any given subject is probably some kind of serious scholarly work,” Jones said. “Not just anecdotal, you know, ‘When I was here 20 years ago, my God…’ That’s the journalist’s way of doing things, usually, is just calling a couple of people up and getting a few quotes.” “The academic research world can be really intimidating and really arcane, and yet, if you really drill down in a lot of studies, there’s a lot of great, usable material.”With grants from Knight and Carnegie, the site originally was designed for journalism teachers and students, featuring teaching notes and exercises (read this related article, write a nut graph). But the target audience now is working journalists. “The academic research world, as you know, can be really intimidating and really arcane, and yet, if you really drill down in a lot of studies, there’s a lot of great, usable material for journalists,” said John Wihbey, an editor and policy journalist at Shorenstein who co-manages the site. For example, search for “campaign finance” at Google Scholar and you’ll get about 567,000 results. It’s dizzying. And the abstracts can be so…abstract. Enter the same query at Journalist’s Resource and you’ll get three. Those three studies pass the Shorenstein Center’s muster for high-quality, peer-reviewed research, and each features a hand-written summary and a link to the original work. (There are even share buttons. How often do you see those on academic sites?) Imagine a presidential election in which the political scientists speed up and the bloggers and political journos…slow down. “What we’re doing is, by hand, going through the political science journals and reaching out to people and saying, ‘Hey, what do you think we should include?’ And then try to boil it down to some core studies on topics of interest,” Wihbey said. “Maybe it’s the case that some of the more sophisticated reporters already know this stuff. But we think it could be useful, and we certainly welcome the whole blogging community that’s not necessarily institutionally affiliated to take a look at all this.” There are more than 420 studies in the site’s database, and the goal is to get to 1,000 by the end of next year. Wihbey gets email alerts from major publishers and constantly monitors Twitter to figure out what studies are being discussed in the press. He said he hopes to get more involved with Mendeley, which is part social network, part information-management tool for academics. He actively encourages scholars and journalists to recommend new studies. Much of the academic world has been slow to embrace the web. Original research is confined to the printed page and PDF, protected by paywalls or private university networks. Academic discourse happens at a glacial pace compared to the speed of the blogosphere. “Some academic disciplines have really embraced the blogosphere pretty well. The economics discipline, for example, there are a lot of very successful economics bloggers who have come out of the academy or sit in think tanks and really get their ideas out there pretty effectively,” Wihbey said. But in the social sciences, “there’s a lot of stuff that’s great but doesn’t necessarily get out there in the way that it should. Part of what we’re doing is trying to create an infrastructure where some of these findings can get greater publicity.” Wihbey says Journalist’s Resource attracts about 11,000 unique visitors per month. One surprisingly strong referrer is Wikipedia, which generates about 15 percent of that traffic, he said. Wihbey occasionally links to stories on his site from Wikipedia pages — not so much for the pageviews, he says, but because it fits in with the mission of the organization. “The phrase Tom Patterson uses,” he says, “is to unlock the scholarship.” Photo by timetrax23 used under a Creative Commons license. |