Nieman Journalism Lab |

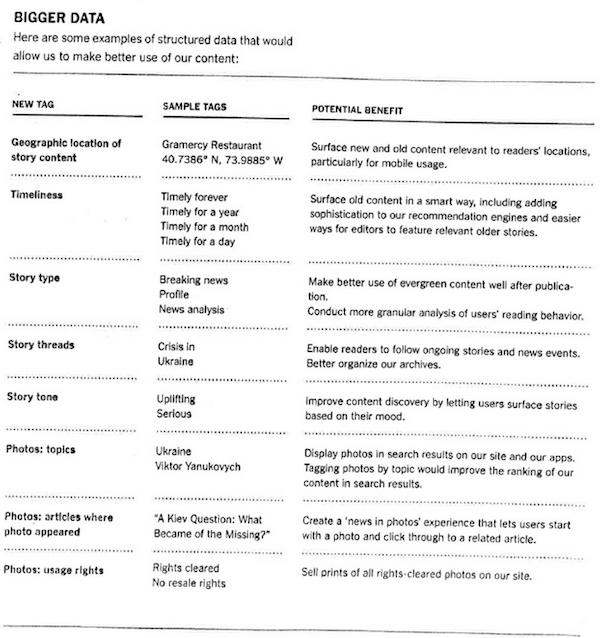

| The leaked New York Times innovation report is one of the key documents of this media age Posted: 15 May 2014 02:55 PM PDT There are few things that can galvanize the news world’s attention like a change in leadership atop The New York Times. Jill Abramson’s ouster yesterday afternoon probably reduced American newsroom productivity enough to skew this quarter’s GDP numbers. We don’t typically write about intra-newsroom politics at Nieman Lab, leaving that to Manhattan’s very capable cadre of media reporters. But Abramson’s removal and Dean Baquet’s ascent has apparently inspired someone inside the Times to leak one of the most remarkable documents I’ve seen in my years running the Lab, to Myles Tanzer at BuzzFeed. It’s the full report of the newsroom innovation team that was given six full months to ask big questions about the Times’ digital strategy. (A summary version of it was leaked last week, but this is the big kahuna.) And that is something we’re interested in here — one of the world’s leading news organizations, giving itself a rigorous self-examination. I’ve spoken with multiple digital-savvy Times staffers in recent days who described the report with words like “transformative” and “incredibly important” and “a big big moment for the future of the Times.” One admitted crying while reading it because it surfaced so many issues about Times culture that digital types have been struggling to overcome for years. I confess I didn’t feel anything quite so revelatory when I read last week’s leaked version — which read like an indoor-voice summary, expected and designed to be leaked to the broader world. This fuller version is quite different — it’s raw. (Or at least as raw as digital strategy documents can get.) You can sense the frayed nerves and the frustration at a newsroom that is, for all its digital successes, still in many ways oriented toward an old model. It’s journalists turning their own reporting skills on themselves. When last week’s version was sent out to the newsroom, a joint Abramson/Baquet memo (their last together?) expressed support for its findings. (“The masthead embraces the committee's key recommendations.”) But I have to say, reading that memo and then the full report, it still feels like there’s a big gap between leadership and the digital troops. Some of that could, understandably, be management’s desire not to air its dirtiest laundry in a newsroom-wide memo. But the tone of the memo is we’re almost there! The tone of the report is these people don’t realize how far away we are. Our media reporter friends are still chasing down why Jill Abramson was fired, and I’m sure in the coming days and weeks, our knowledge of that will grow clearer. The earliest reporting, at least, doesn’t seem to suggest lack of digital vision as a leading significant factor. Baquet had made his biggest marks as an excellent reporter, editor, and manager, not as an online innovator. A big leadership change can sometimes lead to a report like this being put on the shelf; let’s hope that doesn’t happen here. As bad as this report makes parts of the Times’ culture seem, there are two significant reasons for optimism. First: So much of the digital work of The New York Times is so damned good, despite all the roadblocks detailed here. Take those barriers away and think what they could do. And second: While it was a group effort — full list on page 3 here — the leader of this committee was Arthur Gregg Sulzberger, the publisher’s son and the presumed heir to the throne, either when his father retires in a few years or sometime thereafter. His involvement in this report shows that he understands the issues facing the institution. That speaks well for the Times’ future. I asked our three wonderful Nieman Lab staffers — Justin Ellis, Caroline O’Donovan, and Joseph Lichterman — to read through the report and pick out the most important highlights. Those are below. They will be of interest to Times watchers, of course, but it’s much more important that they reach a broader audience. I doubt there is a newsroom in the world that wouldn’t benefit from understanding the cultural issues laid out below. If you have time, read the full report. If not, this’ll do in a pinch. The value of the homepage is decreasing. “Only a third of our readers ever visit it. And those who do visit are spending less time: page views and minutes spent per reader dropped by double-digit percentages last year.” The Times must do a better job encouraging sharing of content: “But at The Times, discovery, promotion and engagement have been pushed to the margins, typically left to our business-side colleagues or handed to small teams in the newsroom. The business side still has a major role to play, but the newsroom needs to claim its seat at the table because packaging, promoting and sharing our journalism requires editorial oversight.” (p. 23-25) Michael Wertheim, former head of promotion at Upworthy, turned down a business-side job leading audience development. “He explained that for anyone in that role to succeed, the newsroom needed to be fully committed to working with the business side to grow our audience” (p. 25) There are about 14.7 million articles in the Times’ archives dating back to 1851. The Times needs to do a better job of resurfacing archival content. The report cites Gawker repackaging a 161-year-old Times story on Solomon Northup timed with the release of 12 Years A Slave. “We can be both a daily newsletter and a library — offering news every day, as well as providing context, relevance and timeless works of journalism.” (p. 28) The report proposes restructuring arts and culture stories that remain relevant long after they are initially published into guides for readers. They give an example of a reader wanting to find the Times’ initial review of the play Wicked. “The best opportunities are in areas where The Times has comprehensive coverage, where information doesn’t need to be updated regularly, and where competitors haven’t saturated the market.” They view museums, books, and theater as the best options for that. Travel and music would be more difficult, the report says. These guides should supplement, not replace current pages. (p. 29) The Times must be willing to experiment more in terms of how it presents its content: “We must push back against our perfectionist impulses. Though our journalism always needs to be polished, our other efforts can have some rough edges as we look for new ways to reach our readers.” (p. 31) Andrew Phelps (full disclosure: a former Nieman Lab staffer) made a Flipboard magazine of the Times’ best obits from 2013 on a whim. It became the best-read collection ever on Flipboard. Why wasn’t the Times doing stuff like that on its own platforms, the report wondered. (p. 33) The product and design teams are developing a collections format, and they should further consider tools to make it easier for journalists, and maybe even readers, to create collections and repackage the content. The R&D department and the new products team have built a “widget-like tool that any reporter or editor could use to drag and drop stories and photos” into a collection. Ultimately this could be something the reader even uses. (p. 34) They experimented by repackaging old content in new formats with a collection of videos related to love on Valentine’s Day and a collection of stories by Nick Kristof on sex trafficking. “The result? Both were huge hits, exclusively because our readers shared them on social.” The Kristof collection page and the articles in it totaled 468,106 pageviews over six days. “Very few articles from a typical day’s paper will garner this much traffic in a month.” Readers spent an average of 2 minutes and 35 seconds on a Kristof story from 1996, for example. (p. 34-35) The Times’ dialect quiz was the most popular piece of content in the paper’s history with more than 21 million pageviews — but projects like that and Snow Fall are not easily replicable. “We have a tendency to pour resources into big one-time projects and work through the one-time fixes needed to create them and overlook the less glamorous work of creating tools, templates and permanent fixes that cumulatively can have a bigger impact by saving our digital journalists time and elevating the whole report. We greatly undervalue replicability.” They point out that competitors like Vox and BuzzFeed view innovating with their platforms as a key function and allow them to create products like BuzzFeed’s quizzes — incredibly popular, but also easy to create over and over again. “We are focused on building tools to create Snow Falls everyday, and getting them as close to reporters as possible,” said Quartz editor Kevin Delaney. “I’d rather have a Snow Fall builder than a Snow Fall.” (p. 36) The Times is planning on creating a section of the homepage that uses reader patterns to customize a list of content that readers missed but would most likely want to see. It’s being planned for the newly redesigned website and iPhone app. “Though all readers would see the same top news stories, the other articles we show them would be customized to reflect what they haven’t seen.” But in order to accomplish this, the newsroom must clarify how much personalization it wants on the website and on the apps; it’ll be difficult to move forward without knowing that. (p. 37-38) The report suggests creating a “follow” button that would allow readers to easily follow certain topics or columnists. What they choose to follow could be sent to a “Following Inbox.” They could also have alerts sent to their phone or email. Before the website redesign, the only way readers could get notified of favorites was by email. The feature had 338,000 users and “unusually high engagement rates” even though it was hard to find and laborious to sign up for. (p. 39) The Times is woefully behind in its tagging and structured data practices. It considered improving its tagging efforts in 2010, but the paper decided not to pursue it. “Without better tagging, we are hamstrung in our ability to allow readers to follow developing stories, discover nearby restaurants that we have reviewed or even have our photos show up on search engines.” (p. 41) Recipes were never tagged by ingredients and cooking time. Because of that, “we floundered about for 15 years trying to figure out how to create a useful recipe database.” They spent “a huge sum to retroactively structure the data.” Structured data problems prohibit the Times from automating the sale of photos and keep Times stories from doing as well in search rankings as they should. (p. 41) It took seven years for the Times to begin to tag stories “September 11.” They need to do a better job tagging articles together and follow a single topic or news event. “We never made a tag for Benghazi, and I wish we had because the story just won’t die,” Kristi Reilly of the archive, metadata, and search team said. The report cites The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and Circa as outlets who the Times could emulate. (p. 41-42) In a section addressing promotion of New York Times content — essentially, social media distribution — the report’s authors survey the techniques of “competitors” and compare them to the Times’ strategy. For example, at ProPublica, “that bastion of old-school journalism values,” reporters have to submit 5 possible tweets when they file stories, and editors have a meeting regarding social strategy for every story package. Reuters employs two people solely to search for underperforming stories to repackage and republish. (p. 43) Contrastingly, when the Times published Invisible Child, the story of Dasani, not only was marketing not alerted in time to come up with a promotional strategy, “the reporter didn’t tweet about it for two days.” Overall, less than 10 percent of Times traffic comes from social, compared to 60 percent at BuzzFeed. (p. 43) Meanwhile, outlets like The Huffington Post “regularly outperform” the Times in terms of traffic, simply by aggregating and repackaging Times journalism. Regarding the deployment of this strategy around Times coverage of Nelson Mandela’s death, a Huffington Post executive said: “You guys got crushed. I was queasy watching the numbers. I’m not proud of this. But this is your competition.” (p. 44) The report advises that simple steps can be taken to lessen the loss of traffic to competitors: “Just adding structured data, for example, immediately increased traffic to our recipes from search engines by 52 percent.” (p. 44) The report points to organizational problems inside the company that contribute to lagging social media promotion and traffic. “Our Twitter account is run by the newsroom. Our Facebook is run by the business side,” they write. (p. 45) In addition, while many in the newsroom are under the impression that the social media team exists to promote their work, that team was in fact originally conceived of as a primarily information gathering body. (p. 45) An attempt to have Times employees experiment with content promotion centered around the Times Magazine’s “Voyages” issue was disappointing. Traffic actually decreased from the previous year, the report states, and overall leadership was lacking — team experts were confused about the tools available to them and tended to err on the side of the conservative. (p. 46) Their response? “Our approach would be to create an ‘impact toolbox’ and train an editor on each desk to use it. The toolbox would provide strategy, tactics and templates for increasing the reach of an article before and after it’s published. Over time, the editor could teach others.” (p. 47) The report invests some time in highlighting the independent social media self-promotion efforts by Times reporters and staffers that have been effective. The authors specifically mention KJ Dell’Antonia, Gina Kolata, C.J. Chivers, Nick Kristof, Nick Bilton, David Carr, Charles Duhigg, and more. (p. 47) Specifically, they point to the fact that many of their best social staffers learned those skills through the book publishing process, not in the newsroom. Their research included an experiment in identifying social influencers, both in the newsroom and outside it, prior to a story being published. The result of their experiment — getting Ashton Kutcher, who has 15.9 million followers, to retweet a Times story — was considered a success. (p. 48) The report also singles out comments as a place where the Times nominally attempts to interact with readers. While the Times takes pride in its ability to encourage discourse while maintaining the brand by moderating its comments, the report suggests this level of engagement may not be sufficient. “Only a fraction of stories are opened for comments,” they write. “Only one percent of readers write comments and only three percent of readers read comments. Our trusted-commenter system, which we hoped would increase engagement, includes just a few hundred readers.” (p. 49) The report suggests the Times consider expanding further into live events. They highlight the success media brands such as The Atlantic and The New Yorker have had with their festivals and conferences. They stress that there is enormous opportunity for both revenue and engagement in the events space for the Times. “There is no reason that the space filled by TED Talks, with tickets costing $7,500, could not have been created by the Times. ‘One of our biggest concerns is that someone like The Times will start a real conference program,’ said a TED executive.” (p. 53)The merging of platforms and publishers has garnered some attention in the media space lately, and the report’s authors do not neglect that conversation. They look at what organizations that allow users to create content on their sites are doing, and question how the Times could develop a strategy without diluting its brand. They suggest that the Times’ audience is full of educated and interesting people who could easily pen valuable content that might find enthusiasm from readers in the digital space. A new push to expand products around opinion reflects this consideration. (p. 52) Interestingly, the report mentions that what readers see as innovation at the Times — graphics and interactives — is not reflected internally, in terms of workflow, organization, strategy, and recruitment. (p. 57) For example, the Times fails to fully take advantage of opportunities to learn about its audience, not doing “things that our competitors do, like ask readers whether they would be willing to be contacted by reporters or if they are willing to share some basic information about their hometown, alma mater and industry so we can send them articles about those topics.” (p. 54) The leadership of the recently fired Jill Abramson is briefly mentioned, including “the significant improvement in relations between news and business under the leadership of Jill, Mark and Arthur.” The authors write: “Embracing Reader Experience as an extension of the newsroom is also the next logical step in Jill’s longstanding goal of creating a newsroom with fully integrated print and digital operations, since these departments have skills to build on our digital successes.” (p. 61) “The very first step,” the authors write about the need for more collaboration, “should be a deliberate push to abandon our current metaphors of choice — ‘The Wall’ and ‘Church and State’ — which project an enduring need for division. Increased collaboration, done right, does not present any threat to our values of journalistic independence.” (p. 61) The report calls for increased communication and cooperation between the sections of the company they call “Reader Experience” and the newsroom. In the report, Reader Experience refers to R&D, product, technology, analytics and design. (p. 63) Those departments are not tiny: roughly 30 people in analytics, 30 in digital design, 120 in product, and a whopping 445 in technology, with around two dozen teams of engineers. (p. 63) Specifically, they praise the recently released Cooking vertical and the NYT Now app, which were spearheaded by Sam Sifton and Alex MacCallum and Cliff Levy and Ben French, respectively. (Other individuals mentioned include James Robinson, Aron Pilhofer, Danielle Rhoades Ha, Kelly Alfieri, and Brian Hamman.) (p. 66) There have been significant obstacles to this kind of cooperation, however. “People say to me, ‘You can’t let anyone know I’m talking to you about this; it has to be under the radar,’ said a leader in one Reader Experience department. ‘Everyone is a little paranoid about being seen as too close to the business side.’” (p.64) The report also describes a developer who quit after being denied a request to have developers attend brown bag lunches along with editorial staffers. This sort of rejection can make recruitment of top developers and designers a challenge. (p. 68) According to the report, there is a sense at the Times that Reader Experience staffers and newsroom staffers are not supposed to communicate. Says David Leonhardt of the process of developing The Upshot, in which he had unanswered questions about competition, audience, platform strategies, promotion and user-testing, “I had no idea who to reach out to and it never would have occurred to me to do it. It would have felt vaguely inappropriate.” (p. 66) The report proposed creating a newsroom strategy team to take some of the strategy work off the masthead: “The core function would be ensuring the masthead is apprised of competitors’ strategies, changing technology and shifting reader behavior. The team would track projects around the company that affect our digital report, ensuring the newsroom is at the table when we need to be.” (p. 71) Times leaders frequently ask former NYTimes.com editor Rich Meislin for advice because other editors and managers, even those tasked with looking at the bigger picture, were too busy. Meislin “remains such a critical resource, providing information, insight and counsel about digital issues to a range of people in the newsroom and on the business side. In addition to having a deep well of institutional knowledge, he also has time. ‘They go to Rich because he’s available and because he’s not dealing with the daily report,’ said a masthead editor.” (p. 72) Even the Times, with all its staffing and other resources — its R&D lab, its mobile team, its editors focused on issues around design, digital, or new initiatives — feels like it doesn’t have the time or power to get outside of the day-to-day grind of making a newspaper to think about its future. Even the mobile group doesn’t have time to look at how the Times can use new technologies, the report says. “That helps explain why it took a group removed from the daily flow of the newsroom — NYT Now — to fundamentally rethink our mobile presentation.” (p. 72) “Another [desk head] suggested that the relentless work of assembling the world’s best news report can also be a ‘form of laziness, because it is work that is comfortable and familiar to us, that we know how to do. And it allows us to avoid the truly hard work and bigger questions about our present and our future: What shall we become. How must we change?’” (p. 72) “‘We’ve abdicated completely the role of strategy,’ said one masthead editor. ‘We just don’t do strategy. The newsroom is really being dragged behind the galloping horse of the business side.’” (p. 72) Rival publications talk to one another and share intel. New York magazine’s Adam Moss said “I talk to [Nick] Denton all the time. We both talk to Jacob [Weisberg]. We’re constantly telling each other what’s working, what we’ve experimented with…About half the choices I make come about because someone from another site tells me something worked, and so we adopt it.” (p. 73) While the business side strategy team is already doing some of that work — they provided an 80-page transcript of interviews about social strategy from talking with other media companies and competitors — the masthead is disconnected from strategy talks: “In recent months, the masthead has been left out of several important studies that will affect the newsroom, including marketing-led exploration of our audience development efforts and a detailed assessment of our…capabilities and needs. In both cases our senior leaders were unaware that these conversations were happening, despite the newsroom’s growing interest in both subjects.” (p. 74) The Times, like many newspapers, does not like failure. It usually doesn’t like to talk about it, in public or in private. “For example, our mobile app, ‘The Scoop,’ and our international home page have failed to gain traction with readers, yet we still devote resources to them. We ended the Booming blog but kept its newsletter going. These ghost operations distract time, energy and resources that could be used for new projects. At the same time, we haven’t tried to wring insights from these efforts. ‘There were no metrics, no target, no goals to hit and no period of re-evaluation after the launch,’ said a digital platforms editor, about our international home page.” (p. 75) The point of the strategy team would be to help prioritize issues that need to be fixed, as well as being able to lend a voice to problems that staff are reluctant to talk openly about. One of the biggest problems is the Times’ CMS, according to the report. “But desks and producers spend countless hours on one-time fixes to the platform, rather than permanent solutions, even when it is clear the problems will emerge again and again. One senior member of the news desk said that leaders would be ‘horrified’ if they understood the situation.” (p. 76) One problem within the Times is consolidating innovation and experiments to a few desks, namely graphics, interactive news, social, and design. The result of this has been that individual staffers and desks, like the news desk, have not had the permission or tools to experiment on their own. The proposed strategy group would help desks work on individual experiments and find ways to replicate that elsewhere in the company. (p. 77) In the triangle of business side, Reader Experience, and newsroom, the newsroom is often seen as defensive or risk averse. “One reason for our caution is that the newsroom tends to view questions through the lens of worst-case scenarios,” the report puts it. “And the newsroom has historically reacted defensively by watering down or blocking changes, prompting a phrase that echoes almost daily around the business side: ‘The newsroom would never allow that.’” (p. 78) The big question: How can the Times become more digital while still maintaining a print presence, and what has to change? “That means aggressively questioning many of our print-based traditions and their demands on our time, and determining which can be abandoned to free up resources for digital work.” (p. 82) A big tension at the Times is what it means to be digital-first, and how the newspaper can get there. Senior editor for digital operations Nathan Ashby-Kuhlman apparently set off a bomb in the form of an email that questioned if the paper was doing enough to prepare for the future. This may not sound revolutionary, but the paper, he argued, needs to focus on digital-first reporting that later flows into a print product. “Years of private complaints around the building suddenly had a very public forum.” (p. 83) On the Michael Sam story, which was brought to the Times and ESPN, the report says the Times “package was well-executed and memorable, but some of our more digitally focused competitors got more traffic from the story than we did. If we had more of a digital-first approach, we would have developed in advance an hour-by-hour plan to expand our package of related content in order to keep readers on our site longer, and attract new ones. We should have been thinking as hard about ‘second hour’ stories as we do about ‘second day’ stories.” (p. 84) The Times’ publishing schedule is out of sync with digital: “For example, the vast majority of our content is still published late in the evening, but our digital traffic is busiest early in the morning. We aim ambitious stories for Sunday because it is our largest print readership, but weekends are slowest online. Each desk labors over section fronts, but pays little attention to promoting its work on social media.” (p. 86) According to the report, The Times doesn’t pay attention to how it presents its content on mobile or within apps. Business Day columnists often show up at the bottom of the business section in mobile because the site loads from the web section fronts. Also, stories and columns often ask people to provide reader comments, but that functionality isn’t available on the iPhone or iPad apps. “Instead of running mobile on autopilot, we need to view the platform as an experience that demands its own quality control and creativity.” (p. 87) Why they leave: They asked 5 people who worked on digital for the Times what led them to leave — Soraya Darabi, Alice DuBois, Jonathan Ellis, Liz Heron, and Zach Wise. None said they regretted leaving. Some quotes: “I looked around the organization and saw the plum jobs — even ones with explicitly digital mandates — going to people with little experience in digital. Meanwhile, journalists with excellent digital credentials were stuck moving stories around on section fronts.” (p. 88) “When it takes 20 months to build one thing, your skill set becomes less about innovation and more about navigating bureaucracy. That means the longer you stay, the more you’re doubling down on staying even longer. But if there’s no leadership role to aspire to, staying too long becomes risky.” (p. 88) The Times doesn’t offer much of a career path for people working on the digital side in the newsroom. And many staffers feel like their skills are either undervalued, or misunderstood. One larger problem for the Times is that there is a shortage of people in senior positions who understand digital news, which also leaves the paper not knowing who should be promoted on the digital side, the report says. “The reason producers, platform editors and developers feel dissatisfied is that they want to play creative roles, not serves roles that involve administering and fixing. It would be like reporters coming here hoping to write features but instead we ask them to spend their days editing wire stories into briefs.” (p. 89) There seems to be agreement from editors, reporters, desk editors and more that the Times spends too much time thinking about Page One. This quote from a Washington reporter helps paint a picture: “Our internal fixation on it can be unhealthy, disproportionate and ultimately counterproductive. Just think about how many points in our day are still oriented around A1 — from the 10 a.m. meeting to the summaries that reporters file in the early afternoon to the editing time that goes into those summaries to the moment the verdict is rendered at 4:30. In Washington, there’s even an email that goes out to the entire bureau alerting everyone which six stories made it. That doesn’t sound to me like a newsroom that’s thinking enough about the web.” (p. 90) On the hiring front, the report says the Times can’t simply assume people want to work for the paper. While ambitious journalists are drawn to the Times, digital talent wants the chance to create something new and experiment. “We can’t pitch ourselves as a great Internet success story, selling potential hires on the satisfaction of helping transform a world-class, mission-driven organization.” (p. 91) But the report also stresses that the paper needs a broader array of digital talent, not just reporters and editors, but “technologists, user experience designers, product managers, data analysts,” among them. The Times also needs to do better hiring the digitally-inclined into leadership positions rather than waiting to promote from within, the report says. When the Times promoted Aron Pilhofer and Steve Duenes to associate managing editor positions, both improved the hiring efforts on the digital side, the report says. (p. 91) On finding and developing digital talent, the report has a variety of recommendations for things inside and outside the building, including finding ways to empower the current staff to do more, identifying the top digital talent in the newsroom and giving them opportunities. But the Times also needs to “accept that digital talent is in high demand. To hire digital talent will take more money, more persuasion and more freedom once they are within The Times — even when candidates might strike us as young or less accomplished.” Another idea? Make a big splash: “Make a star hire,” because top digital talent can help bring in similar-minded people. (p. 96) Photo of the Times building by Alexander Torrenegra used under a Creative Commons license. |

| The newsonomics of spring cleaning Posted: 15 May 2014 09:13 AM PDT The tensions of change in the news business are intense but often subterranean. One way they pop into public view is through top leadership changes, something that seems to be happening more frequently today than in the past. In the span of a few hours yesterday, we saw both Jill Abramson’s ouster at The New York Times and the resignation of Le Monde’s top editor. It wasn’t that long ago that Daily Telegraph editor Tony Gallagher was shown the door. These events are always about a mix of leadership, personality, change management, and big questions about how authentic editorial values will be maintained in an era of roiling business challenge. But despite the attention they grab, they’re only a tip of the iceberg. As we look forward to the second half of the year, we already know some of the big stories to watch, and leadership will be key to those. How will the spun-off Tribune and Time Inc. companies do, and how will they be led? As Jeff Bezos’ ownership of The Washington Post reaches the one-year mark, will the revolutionary disruptor announce any shape-shifting moves for the Post — moves which might serve as models for his besieged new brethren? Who will buy the dozens of former MediaNews and Journal Register properties that Digital First Media will be putting on the block? But let’s focus on the major changes we’re seeing now instead of looking ahead. It’s been a season of positioning, movements less seismic than slowly shifting. It’s a season that is seeing a lot of housecleaning and — barely noticed — the crumbling of some of the newspaper industry’s vestigial structures. Let’s start there, with one announced dissolution, and then check in on three other storylines involving many of the long-established players in the U.S. daily industry. The wires business recedes farther into the 20th century.Once there was a flourishing “supplemental” wires business — all those wires that complemented the Associated Press (and, long ago, United Press International). The epoch spoke to the robustness of the news business. Many newspaper companies invested in content, both using it themselves and finding buyers among their newspaper peers. It wasn’t unusual for a half a dozen wires to flow into news desks every day. Back in the ’90s, we counted how much content flowed into the St. Paul Pioneer Press each day and how much of it we used. We printed just 5 percent of what we received. Retired Scripps Howard News Service editor Peter Copeland neatly recounts a two-decade tale of consolidation and loss.

Whew. Tribune and McClatchy announced that latest move last week, with McClatchy selling its half share. We know that Tribune — which has long run the business side of the wire but will now take over editorial operations as well – is consolidating the wire in Chicago. Layoffs of the D.C.-based editing staff are in progress, though it’s important to point out that both McClatchy and Tribune will maintain their D.C. reporting bureaus. We can expect that the Chicago Tribune will leverage its position as a central hub for the current Tribune chain in reorganizing what will become a Tribune wire. Tribune has already said it would meld the operation into the Tribune Content Agency. So what has been a roughly break-even venture will become part of a profit center. Expect new packaged products, something the Chicago Tribune has gained in proficiency in over the past several years. How will the hundreds of newspaper clients of the wire react? Will the fact that it will soon be more a Tribune company than a quasi-coop (some newspapers contribute content to the wire as well as receive it) make any difference to them? The move tells us a lot about newspapers and content. The supplemental wires have remained largely print-oriented, and as newspapers have finally gone more local in print and cut newsprint overall, there’s less space for wire copy. In addition, relatively few newspapers have made effective use of this niche-y content — the McClatchy Tribune wire has distinguished itself with strong features across a variety of topics — in their digital products, one of the failures of imagination evidenced over the years. Now new syndicators like NewsCred bring new models of audience-targeting content licensing to the marketplace. Wires fade into the history books.Gannett is now an advertising company.Last June, when the largest U.S. newspaper publisher bought Belo TV stations, I said that Gannett had become a TV company. Now, with the latest likely move — buying Cars.com outright from its newspaper partners — we’ll have to adjust that description (“The Newsonomics of selling Cars.com”). The best new description may be this: Gannett is an advertising company. Of course, it’s always been a major ad seller, but as its newspaper ad revenue has cratered along with the rest of the industry’s — down more 50 percent over the last seven years — the company has looked for new ways to generate replacement profit.Adding the Belo TV stations to longstanding Gannett Broadcasting made it one of the top four broadcast players in the country. Just yesterday, it bought six more Texas stations to add to its standing. The logic: Broadcast may be maturing, but it’s not gasping for its breath like newspapers are. The Belo deal meant that Gannett would plan to see two-thirds of its operating income come from broadcast, a dramatic turnaround once for what was once the plumpest of cash newspaper cows. That broadcast money is mostly advertising, bolstered by a healthy stream of retransmission fees paid by cable and satellite companies — though those fees are increasingly under legal and competitive pressure. Now if it completes the Cars.com deal, it will add as much as $350 million in additional advertising revenue to its mix. (I expect Gannett will partner with private equity to buy Cars.com, which may complicate the accounting.) Add it up, and we get to the ad company definition. We can figure that at least 75 percent of Gannett’s revenues will be ad dependent. While that’s better than being an ad-dependent newspaper company, such a reliance could be problematic. Digital disruption is slowly eroding the broadcast ad business. While Cars.com has an enviable No. 2 position in its sector, its new competition will come from all sides, known and unknown. The question for Gannett’s shareholders, and employees: Has the company charted a strategically defensible future, or just bought a few years of time? As Gannett finalizes its Cars.com buy, exiting the business ownership will be McClatchy, along with Tribune, A.H. Belo, and Graham Holdings. All those companies exited Apartments.com earlier in the year, selling to private equity. Group the three transactions — Cars.com, Apartments.com, and the McT wire dissolution — and we see the partnership culture of an earlier generation fading fast. New national news networks are forming.Look back in time 20 years and you’ll find plenty of ideas for creating a reader-accessible site for most newspaper-produced content: a portal for all the news from the country’s 1,350 or so dailies. Start with New Century Network, one such mid-’90s effort that hardly left the gate. Knight Ridder’s Real Cities was a pretender as well. At various times, Yahoo News has aggregated lots of newspaper content. Still, in 2014, there’s no simple-to-use, single place to go for to tap into newspaper content overall. This year, we see new stirrings. Expect to see the next upgrade of the Associated Press’ AP Mobile app soon. Since its launch in 2008, it’s been an intriguing product, embracing that broad expansive network notion. AP identified the green fields of mobile early and convinced hundreds of newspapers to contribute to the mobile-only product. AP Mobile gets impressive traffic, but mainly to its own national and global content; local content drives less than 20 percent of its traffic. The key going forward will be the user experience: How do you present many firehoses of reader-relevant national and local daily content in a way that makes sense, especially on a tiny smartphone screen? Consider, also, the new Washington Post network plan. The idea: Allow newspaper partners to show Washington Post content to their own subscribers. Certainly, it’s small today, and nothing like an all-inclusive networ; a half-dozen newspapers — The Dallas Morning News, the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, The Toledo Blade, the Minneapolis Star Tribune, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel — have signed on. The business deal: Affiliates offer up otherwise paywalled Post access (without additional cost), increasing their own reader value propositions. The Post gains more ad inventory. No money changes hands.Post president Steve Hills tells me that the program will expand rapidly, intending to serve “multiple millions” of the roughly 30 million U.S. newspaper subscriber population. Although Hills says there are no plans to create a single authenticated user experience, we can see how the Post network could grow into such a product – and do so within paid digital circulation strategies. If we expect new Post owner Jeff Bezos to break some traditional business molds at some point, wouldn’t such a networked approach be a logical one? The potential of an integrated iTunes for News experience may be in the back of the Bezos brain. Then, there’s the newly launched Dutch Blendle model. It’s innovative, and it pushes into the one area that the Netherlands dailies would allow for aggregation: pay per article. Blendle is aiming at other markets, though don’t expect it to land on American shores soon.The obstacles to creating a state-of-the-art network experience are formidable. How do you avoid cannibalizing reader revenue in an age of individual paywalls? How do you share new revenue, and how do you give readers what they really want? They may be insurmountable. Further, the growth of compelling news content well beyond newspapers is so great that it’s possible a newspaper-only product no longer makes sense. Still, expect the dream to be pursued. The new News Corp’s colicky infancyLast week’s News Corp’s financials told us the company hasn’t yet figured out its post-spin-out way forward. The big number: Down 9 percent in its news and information segments, with both ad revenue and reader revenue down. Even with some allowance for currency impacts, the results lag its peers. While the problems of News Corp can be found on three continents (Australia, U.K., and U.S.), it’s the American face-off with The New York Times that must grate Rupert the most. So far, the Thompson vs. Thomson face-off I described as both companies hired new CEOs has gone in favor of BBC transplant, NYT CEO Mark Thompson. Compare The New York Times’ recent growth (“New numbers from the New York Times”), in both ad and reader revenue, to News Corp and you see one company in modest turnaround, the other still looking for it.There are a couple of reasons to believe this battle is still in the very early stages. As it released its problematic numbers, News Corp announced the expected appointment of Will Lewis as CEO of Dow Jones, removing his “interim” title. The early reports on Lewis’s DJ/Wall Street Journal are good ones. The damage done by Lewis’ predecessor as CEO, Lex Fenwick, though, will take at least a few quarters to repair, even as the wider competitive markeplace around Dow Jones moves on rapidly. Lewis’ listening tour is now over, and the painful reconstruction of the company’s Factiva/B2B business has begun.How painful? News Corp CEO Robert Thomson described the B2B do-over this way on the financials call: “At Dow Jones, where we had obvious difficulties with our business-to-business offering, the team has started to stabilize the institutional revenue and refined our product and pitch.” That’s painfully honest, with a tad of spin. Product and pitch cover the whole business. Meanwhile, Lewis must get the consumer side of Dow Jones — largely the Journal — reenergized as well, just as energetic turnaround tests are in midstream at News Corp properties in Sydney and London. The current shakiness of the company is buoyed by two hard realities: Rupert Murdoch and money. Just this year, Rupert bulled through his family succession plan and this week moved forward with a long-planned effort to create a consolidated Europe-dominating Sky TV company through his other company, 21st Century Fox. The man lies in wait for opportunities, showing the doughtiness of a man a third his age. Then, there’s the cash. News Corp’s the best-funded news company on the planet, and that can make the recent Dow Jones chaos and current financial woes mere speed bumps on the long Murdochian road ahead. Photo of Lego cleaning by Bas Van Uyen used under a Creative Commons license.[/ednote] |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

And at TechCrunch Disrupt last week, Lerer

And at TechCrunch Disrupt last week, Lerer  A

A

Cooking is a rich area for digital news experimentation, because while new pieces are added all the time, a six-year-old recipe is almost precisely as valuable to the reader as one published yesterday. It’ll still taste good! It’s a test of the strength of an outlet’s archives and a site’s ability to surface content within them. The new site’s collections feature is aimed at exactly that: A

Cooking is a rich area for digital news experimentation, because while new pieces are added all the time, a six-year-old recipe is almost precisely as valuable to the reader as one published yesterday. It’ll still taste good! It’s a test of the strength of an outlet’s archives and a site’s ability to surface content within them. The new site’s collections feature is aimed at exactly that: A