Nieman Journalism Lab |

- Q&A: Clark Medal winner Matthew Gentzkow says the Internet hasn’t changed news as much as we think

- NewsLynx wants to build tools to better measure the impact of journalism

- How 10 news organizations look at issues of online engagement

| Q&A: Clark Medal winner Matthew Gentzkow says the Internet hasn’t changed news as much as we think Posted: 29 Apr 2014 09:19 AM PDT The Clark Medal is one of the most prestigious awards in all of academia, awarded to the “American economist under the age of forty who is judged to have made the most significant contribution to economic thought and knowledge.” (Names you might know among previous winners: Paul Krugman, Milton Friedman, Joseph Stiglitz, Steven Levitt, and Larry Summers.) This year’s honor went to Matthew Gentzkow of the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business. Gentzkow is a pioneer in the field of media economics; his work, often co-authored with Chicago Booth’s Jesse Shapiro, takes advantage of previously unavailable data on audience, content, and media impact. Austan Goolsbee, also a Chicago Booth professor, commented on Gentzkow’s work in The New York Times:

Some of Gentzkow’s most talked-about research has been on bias in news sources — he’s written papers around measuring slant, whether readers consume diverse or confirmatory news, and whether there is a demand for biased news in the market. He’s looked at the impacts of television on children and on voting behavior, and he’s has studied online advertising. Going forward, Gentzkow said he’s interested in looking at more international media — he’s focused on finding a comprehensive data set for global media content. He’s also excited about the potential for data created by geocoding and cellphones, as well as studying media impact on the individual level — maybe even with electrodes. We talked about the cost of information gathering, the demand for quality news, and the obstacles to gathering data; here’s our lightly edited conversation. Caroline O’Donovan: Congratulations! I think I read that you now have a one-in-three shot of winning a Nobel. My question is: Can you build a predictive model that tells us what year you’re going to win the Nobel? Matthew Gentzkow: I think I should refrain from speculating on that. The scary implication of this kind of thing is you don’t want to be remembered as the one guy who won this prize and then didn’t do anything very interesting afterward. One might think, if you’re lucky enough to win an award like this, then you can kick back and relax. But it doesn’t really feel like that. It feels like now I have a lot of work to do to try and live up to this vote of confidence from my colleagues. O’Donovan: This is one of those wunderkind awards that specifically exists to make you feel like you have a lot of work left to do. Gentzkow: I don’t know if 38 years old still counts as a kind, but I’m happy if it does. I think there is some notion in awards like this of recognizing people while they’re still working, as opposed to once it’s all done. O’Donovan: But joking aside, the whole idea of all this new, deeper data being available — that’s not going away, right? So there’s certainly a lot left for you to get into. Gentzkow: Oh, absolutely. It’s an incredibly exciting time to be involved in economics — to be involved in science broadly. There’s more and more data everyday. I think what everybody will be able to do 10 years from now will make this year look kind of puny. The challenge is trying to keep up, keep close enough to the frontier, keep learning new things, keep up with all these smart graduate students who are getting their PhDs and know a lot more than I do. Try to keep producing new research. It’s challenging, but certainly the data and the technology are going to keep getting better, and that makes it exciting. O’Donovan: To dial it back a little bit, what made you decide that media economics was something you were interested in? I assume it wasn’t, The data around this issue is going to explode, and I want to be the guy that was known for taking advantage of that. So how did you get interested? What were the big questions that were driving you? Gentzkow: It was certainly not as far-sighted as that. The immediate thing was: I’m a graduate student, I need to find a topic for a dissertation so I can get my degree and get a job. So for me, like a lot of people, it came out of this process of casting around, looking for topics, talking to your advisor. Once I stumbled on it, it was a really good fit. There was a mix of interesting, rich economics that it seemed like other economists might find interesting, but also this broader set of political and social questions. Media is in some sense a market like any other market, but it’s interesting above and beyond the usual reasons because of the way it effects the political process. It’s something that the typical American spends three or four hours a day doing. I never worked in business — I didn’t do consulting or investment banking. Some of the things people traditionally work on, I didn’t have exposure to. Newspapers and TV and the Internet were things I felt like, as a consumer, I had some intuition about, thought about, found myself asking questions about. It was a good fit for me to work on something that had already piqued my curiosity. O’Donovan: Are there areas of it that you feel especially excited about, getting the answers to some of those questions? Gentzkow: Things that I would love to work on and other people are working on — one is ongoing changes in online media. So things like social media and how that’s changed the landscape of where people get information and how. The way the business of media has changed online continues to be a really challenging and exciting question. Understanding online advertising markets, and how they work, this big question in the background — has the business of journalism changed in a way that we’re not going to be able to support? How is that going to play out at local levels? National levels? And a third thing is how similar sorts of things play out in different countries around the world. Whether the U.S. media is a little bit conservative or a little bit liberal, that’s sort of important. But what’s happening in Russia, in China, in the Middle East, what happened in the Soviet Union, in communist countries — in those sorts of settings, there’s an order of magnitude bigger impact in some ways. O’Donovan: Can you walk me through the difference in availability for those micro U.S. questions versus the more international questions? Where would that information come from? How do you get it? What are the difficulties or challenges to getting it? Gentzkow: So, if you want to look at news text currently, say in the last year across lots of different countries, that is already easily available. Google News has sites for lots of different countries. Part of what’s really exciting is, it’s sitting right there. Now, doing that in practice is a little harder. Jesse [Shapiro] and I several years ago had a project where we were trying to aggregate news content from lots of different countries, partly with some help from Google News, and the computational challenges, the challenges of getting everything into a form where it was clean enough that you could do something with it, proved to be pretty hard. We ended up putting that project on the back burner because we couldn’t quite get it all to come together. O’Donovan: Google is cooperative with that kind of research? Gentzkow: They tend to be cooperative. Google has a history of being very cooperative with researchers, at least to the extent that it doesn’t impose some huge cost or burden on them. They were very helpful about letting us access the database from Google News of the news stories they had archived each day, so we could go out and scrape the text of those things. That was really due to one engineer there who used some of his free time to set that up and do it. So I’ve found them to be extremely helpful. Obviously, it’s a business, so they’re going to be more reluctant to do things that require huge costs on their part. O’Donovan: So you could scrape everything on a day and keep it all? Gentzkow: We could scrape it and keep it. There’s some sensitive copyright issues around them giving us directly the archive of text from all of those sites; they were giving us the URLs and we were going out and storing the HTML text from those URLs ourselves. Again, this is an example of a project we never actually figured out how to do well enough to write a paper about it. Somebody just showed me a website1 which is not primarily academic, where they actually have a very large number of sites around the world. They’re scraping them and categorizing them and backing out from them; automated measures of what events are happening — where, when, mapping them. It all sounded very exciting. O’Donovan: When you’re thinking about chunking media types — you have some studies that are about newspaper content, and then some about broadcast and television, and then digital — how do you think about breaking those things down and making them comparable, if they can be comparable at all? Gentzkow: Well, video is really hard. Obviously, automated content of video is something we’re still not very good at. Google’s working hard on that problem, so you can search for things, but that’s beyond my abilities. But in terms of text, I think in the digital space, pretty much everybody’s competing with everybody, so it makes sense to think of that as one market, whether it’s ABC.com or NYTimes.com or NPR.org. Whatever traditional media you’re coming from, once you’re putting content online, you’re competing in the same marketplace. Newspapers in the 19th century, TV in the 1950s, daily print newspapers in the U.S. in the mid-2000s — that’s something different. There is a theme running through this work: that the differences across media (in the sense of medium) are smaller than people often imagine. A lot of the underlying economics is the same online as it was for print newspapers and TV, and as it was in the 19th century. I think that’s part of the lesson that comes out of all of this — that maybe, things don’t change quite as much as we think. O’Donovan: Can you give an example, or expand that a little bit? Gentzkow: One of the projects Jesse Shapiro and I worked on, the study of ideological segregation online — the motivation for that paper was, there’s been a lot of discussion about the idea that because there’s so much variety available online, it’s going to allow people to self-segregate. Conservatives only look at conservative stuff and liberals only look at liberal stuff and neo-Nazis only look at neo-Nazi stuff and vegetarians only look at vegetarian stuff. Nobody gets any information that contradicts them. The purpose of the paper was very simple: Let’s go look at some data on the way people actually consume news online and see to what extent that’s true. Conclusion: not nearly as much as you might think. If you ask why not, the answer is because the Internet is not all that different from any other medium. The key thing driving low segregation online is that most people get most of their news from a very small number of sites. They get their news from CNN.com or Yahoo.com, NYTimes.com, Fox News — a huge share of news consumption is a small number of big sites that are very much in the middle of the spectrum in terms of their audiences. Why is that true? Why haven’t we instead seen something a little more like the scenario Cass Sunstein was talking about, where everybody reads their own niche site and there are thousands of different niches and each person is in one of them? Because it remains true that the fixed costs of producing good news are still really high. It’s easy to put up a website, but to produce original reporting news content is still really expensive. Creating a website like CNN.com that covers everything that’s going on and that people trust and believe in is hard, is expensive. So you end up with, just like in lots of other media markets, a small number of firms control a large share of the market. Those firms that invest all that money in quality are not going to do that and then cater to the neo-Nazi vegetarian tiny little corner of the market. They’re going to position themselves in the center to appeal to a wide audience. The economics that drove the finding in that paper, I think, are the same economics that explain why we see what we do in TV and why we see what we do in print newspapers. The details are different, the cost structure is different, but basically the production of news remains not actually all that different. That shapes in a big way the outcomes that we see. O’Donovan: That’s interesting, because that puts the reporting at the center of the cost to the news company, which I don’t think we talk about much. Gentzkow: News companies are doing a few different things that are distinct. One is producing information — that is, reporters going out, collecting information, writing stories. A second is filtering and interpreting it — picking which one of the 25 stories we’re going to put on the front page. And a third is delivering it to people, physically, through the wires into their TV or throwing it on their doorstep with the print newspaper. The Internet has dramatically changed the technology for delivering information to people, and it’s also pretty dramatically changed the extent of competition and filtering and interpreting information. But it really hasn’t changed all that much the production of news. If we want to learn what’s happening in Afghanistan, pretty much somebody has to go to Afghanistan and put their lives at risk and take photographs and interview people. Those things have changed some — yes, there’s crowdsourcing, people upload videos from their phone. And yes, lazy reporters can just sit at home and do research on Google, where they don’t actually have to go down and sit in a city council meeting. But I would say relative to changes in other parts of the business, the way reporting has changed is much smaller. I think producing good news stories remains something that’s very costly, requires a lot of skill, a lot of talent. That remains the scarce resource. That explains why the Internet isn’t quite so different as we might have thought. O’Donovan: I guess the fear there that you sometimes hear is that, if there’s a slow attrition of quality over time, then the reader no longer expects the same consistent level of quality news, then that might actually be disrupted. Gentzkow: Like I said, I think to what extent the ability of the market to support high quality journalism has changed, or is changing, or will change, is a really important question, and not one I know the answer to. I am more optimistic than some people about it. I don’t really buy the view that we train consumers to care about quality or not care about quality. I think the desire of people to know what is going on in the world from a source that they trust, that they believe is accurate, is a feature of humanity that’s been there for a long time. People in the Roman Empire cared a lot about getting the news, people in Medieval Europe cared a lot about getting the news, people in the 1920s cared a lot about getting the news, people today care a lot about getting the news. O’Donovan: How does what you’re talking about — the demand for quality news — fit into the work you and Jesse have done on the consumer demand for biased news? Gentzkow: There’s a really important clarification with that paper. The media slant that we’re measuring in that paper has no notion of good or bad attached to it. We are measuring based on the phrases that newspapers use, based on their content, which newspapers are to the right or left of which other newspapers. There is no notion in that paper of more or less slant, or more or less bias. All we can do is line people up from left to right. What we’re picking up are decisions like: We have to call these people either undocumented workers or illegal aliens. Both of those terms are loaded, both have strong political connotations, we have to pick one or the other. People might debate this, but in my view there’s no such thing as the objective, correct term. Which decision you make will put you either to the left or the right, but it doesn’t make you better or worse or more or less accurate. Saying that newspaper slant is driven by the readers doesn’t mean that catering to the readers is making newspapers worse or more biased or less accurate or lower quality. It just says: These differences we see, that some sound way to the left and some sound way to the right, are shaped by making the decisions that will appeal most to those readers. There’s a separate question that we don’t take up in that paper which is: How does catering to readers affect quality? For example, maybe really all that people want to read about is celebrity gossip and scandals and local crime, and media end up covering those things to the exclusion of political debates or something that you think might have valuable social effect. Does catering to consumers make media more lowbrow, highbrow? I think local crime is actually pretty important; political scandals are an important part of politics. Judging what news content is good for society and what news content is bad for society is a little bit of a tricky business. But I think it’s still a really interesting question. O’Donovan: I was going to say, how do you even measure what’s highbrow or lowbrow? It dovetails interestingly with this trend toward explanatory journalism, because it’s the difference between content and tone. We’re used to tone reflecting content — The New York Times uses these fancy titles for people, because it’s the Times and it’s good journalism. When we mess with that, what are we saying to our readers? Gentzkow: There are ways to measure highbrow versus lowbrow. You can measure the length of the words that you’re using, you can measure how dense the text is, you can look at what kinds of words tend to be used by outlets with highly educated readership versus less educated readership. I think the challenge is getting some measure like that that you’d be willing to attach normative meaning to and say “higher is better for society.” I think that is very difficult. It’s not clear that the world would be better if all media was designed to appeal to people with PhDs. I think in that world probably nobody would look at media — nobody would learn anything. O’Donovan: I know you have to run, so just one more question. I really liked the language Austan Goolsbee was using to talk about you to other reporters — he called the data sets that you were using “unfathomable” and said these were “unprecedentedly grand ambitions.” For you, is there a dataset out there — maybe it exists, maybe it doesn’t, maybe you know where it is, maybe you don’t — but is there something, if it was quantifiable, that you’d want as your next dataset? Gentzkow: It’s a good question. Really being able to see all the media content being produced across all the countries in the world is one. I think things at the individual level give you more insight into how people are reacting. Ideally, the hypothetical dataset is to look inside everybody’s head and see their beliefs and how they’re thinking about things. So maybe we can put electrodes in peoples’ brains and come up with a way to measure that directly. Another thing that’s out there is all this geocoded data coming from the fact that everybody’s cellphone now tells you where everybody is every minute of the day. I don’t know what I’m going to do with it, but that’s going to be a huge area of research going forward. Photo of Gentzkow by the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Notes

|

| NewsLynx wants to build tools to better measure the impact of journalism Posted: 29 Apr 2014 07:50 AM PDT A new research project over at Columbia’s Tow Center wants to do a better job of determining the real impact news has on the world around us. Former Knight-Mozilla OpenNews fellows and current Tow fellows Brian Abelson, Michael Keller, and Stijn Debrouwere hope to find new ways to both quantitatively and qualitatively measure the impact of journalism with NewsLynx. To that effect, they’ll be working with the over 100 members of the Investigative News Network, trying to figure out how impact is measured and what the goals are in those newsrooms. Their first step will be to build a standardized taxonomy for talking about impact across organizations. This list gives a sense of what next steps will be:

NewsLynx is also likely to be the first news research project to launch with a reference to the Borgesian Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge. |

| How 10 news organizations look at issues of online engagement Posted: 29 Apr 2014 07:18 AM PDT How do you measure success in the digital sphere? How should news organizations interact with their audience? What’s the best way to personalize content for individual users? These were among the topics discussed over the course of two days in February as representatives from 10 different news organizations gathered around a conference table in Austin to discuss the challenges (and opportunities) wrought by the Internet. This particular discussion was facilitated by the Engaging News Project at the University of Texas, which brought together the journalists — which hailed from organizations like The Wall Street Journal, The Sacramento Bee, NPR, and The Texas Tribune — for a workshop on digital best practices and ideas for future experimentation. “These sorts of conversations provide a space for organizations to work together, and I think there’s an increasing realization that for the news space to survive it’s in people’s interest to have some collaborations,” said Talia Stroud, director of the Engaging News Project. The Engaging News Project this morning released a report summarizing the discussions which highlights various points and thoughts shared by the participants during their conversations. Here are a few highlights. Measuring successNew technologies have allowed news organizations to tell stories in different ways online, but many still aren’t sure how to best tell a story or present information online. “How do we know whether an [interactive] infographic is better than some old-school bar chart?” Stroud asked. “This is such a profound question, right? How do we know whether the things we’re doing are working or not?” But back up: How do you even define “working”? Advertisers have their own favored audience metrics, but are they the best way to measure user engagement? The focus is often on time on site and repeat visits, according to Tom Negrete, The Sacramento Bee’s director of innovation and news operations. (The report paraphrases the participants’ points rather than quoting them directly.) But he argues newsrooms and journalists have an obligation to go further, to measure comprehension: Can an individual understand what was just read in a news story? To try to address this very issue, The Daily Beast has introduced a value-per-visitor metric which measures how visitors to the site read, comment, tweet, share, email, click a link, and click an app, Mike Dyer, the Daily Beast’s chief digital officer, says in the report, noting there is an economic and journalistic value to each of these actions. The Daily Beast has found, for instance, that standalone infographics are shared 300 percent more often on social than traditional articles on a similar topic. Late last year, Daily Beast staffers began meeting monthly to discuss metrics on stories, and since then monthly referrals have increased about 30 percent, Dyer said. Measuring success is further complicated in places where there’s a traditional print or broadcast platform coexisting with digital. At The Wall Street Journal, there’s a push and pull between modes of thinking, according to Jonathan Keegan, the Journal’s director of interactive graphics. “A staffer may design a stand-alone infographic,” he’s paraphrased as saying in the report. “Copy editors may wish to hold the infographic to run alongside a news story. That is print thinking. We are getting better at realizing that graphics can go up on the site at any time.” Improving reader engagementComment sections on news websites have long been derided as breeding grounds for uncivil discourse and extreme opinions. Many of the participants in the roundtable were frustrated by their comments sections and were interested in finding ways to foster more productive reader engagement. There were various suggestions on how to reimagine comments — from inline commenting to encouraging commenters to respond to a specific question posed about the article. A consensus among the participants was that increased interaction with newsroom staffers could help with the civility dilemma — but they also acknowledged that many newsrooms do not have the resources to devote staffers to mind the comments. Sasha Koren, The New York Times’ deputy editor of interactive news, cites the Times’ “active moderation” approach, noting that while it is heavily resource intensive, the work done to encourage meaningful comments has significant benefits for other readers. (Still, some suggested that it’s best for reporters to stay out of the comments section. Charles Mahtesian, NPR’s politics editor for digital news, said he suggested that route because you can’t “win” against an angry commenter and dipping into the mire can be discouraging for reporters.) How news organizations approach personalizationThere was a wide disparity in how the participating news organizations thought about personalizing and segmenting their content for users, and the discussion identified seven different approaches for segmenting content: by topic, by demographics, by past site behavior, by how people come to the site, by platform, by location, and not segmenting content at all. Stroud said she was surprised by how varied the different approaches were across news organizations, but added that all the differences could ultimately be beneficial for all news organizations. “If we want to know what works, we have to get some mechanism for assessing these sorts of things so we can distribute that information,” she said. Again, check the full 21-page report for more about what was discussed. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

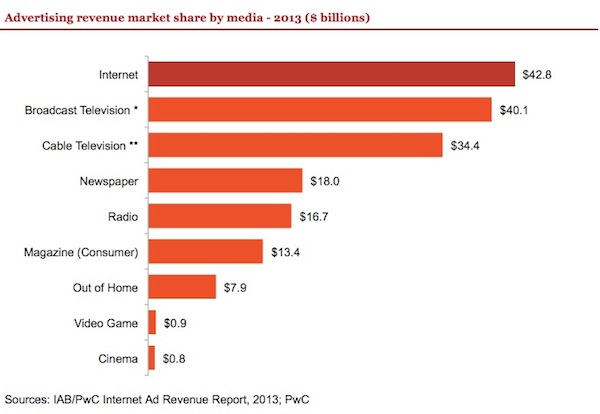

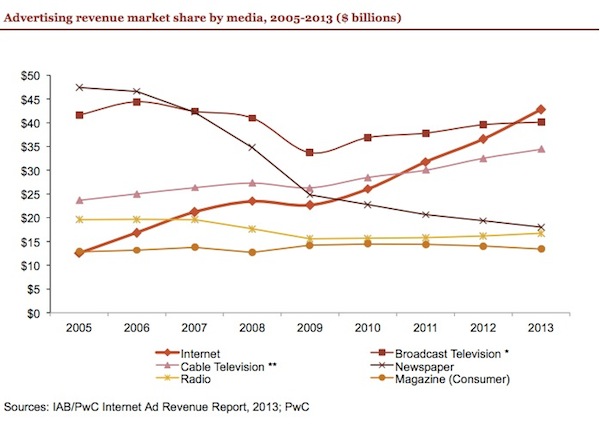

So, as digital advertising overall grew by $6.2 billion in a year, newspapers’ digital ad take increased by only $50 million — less than one percent of that six-billion-dollar growth.

So, as digital advertising overall grew by $6.2 billion in a year, newspapers’ digital ad take increased by only $50 million — less than one percent of that six-billion-dollar growth.

![FB Newswire_news1[1]](http://www.niemanlab.org/images/FB-Newswire_news11.jpg) Facebook is of course a major source of traffic referrals for many news organizations — half of BuzzFeed’s

Facebook is of course a major source of traffic referrals for many news organizations — half of BuzzFeed’s ![FB Newswire_viral1[1]](http://www.niemanlab.org/images/FB-Newswire_viral11.jpg) For Storyful, which will run the page, FB Newswire serves as an opportunity to showcase its brand and products to a larger audience, said

For Storyful, which will run the page, FB Newswire serves as an opportunity to showcase its brand and products to a larger audience, said