Nieman Journalism Lab |

- In Australia, an ambitious nonprofit news outlet has its funding pulled out from under it

- The New York Times drops its mobile-app meter from 3 articles a day to 10 a month

- Guide ditches news anchor avatars in favor of a streamlined, automated video production

- The newsonomics of the for-profit move in local online news

| In Australia, an ambitious nonprofit news outlet has its funding pulled out from under it Posted: 30 Jan 2014 06:13 PM PST Editor’s note: When I speak to journalists or news executives from other countries, there’s one part of the American news ecosystem they’re always amazed by: our nonprofit news outlets. From ProPublica to the Texas Tribune to the smallest two-person startup waiting for 501(c)3 status, most countries have little or nothing like them. (There are a number of reasons: larger roles for state-funded media, fewer large foundations to offer support, less of a tradition of private philanthropy.) One of the counterpoints to that generalization has been The Global Mail, an Australian site funded by Internet entrepreneur Graeme Wood, who in 2012 pledged to give at least $15 million Australian (roughly $13 million in American dollars) over five years. But on Thursday Wood said he will no longer fund the site, leaving its future in question. It’s an imperfect metaphor, but imagine if the Sandlers had suddenly stopped funding for ProPublica 23 months into its life. Here, in a piece from another Australian nonprofit media site, The Conversation, Australian journalism academic Alexandra Wake looks at how its potential closure could affect the nation’s media ecosystem. There are no great surprises in the announcement by Wotif founder and philanthropist Graeme Wood that he will no longer fund not-for-profit online journalism venture The Global Mail (TGM). According to reports, Wood initially pledged A$15 million to the project and expected nothing immediately in return apart from quality journalism, saying in 2011:

While Wood got his quality journalism without a piece of advertising to destroy reading pleasure, he has still chosen to cease funding the site from February 20. The site is now urgently seeking another backer. The product was good, featuring some of the best work by some of Australia’s finest journalists. TGM won multiple awards, not just under the leadership of foundation editor Monica Attard, but also those who followed under Attard’s replacement Lauren Martin. It also attracted readers — not the click-baiters who read a headline, click and run — but those who stay on site for between five and 10 minutes. TGM’s 2013 readership peaked in May with over 315,000 visits and 258,000 unique visitors, while the monthly average for the year was 120,000 uniques. Its initial audience on launch in February 2012 was 97,000 unique visitors. In December, Wood suffered a personal financial kick (reportedly as high as A$48 million) after Wotif’s share price plunged almost 32 percent off a profit downgrade. Wood, whose stake in Wotif stands at 20 percent after selling just under two million shares in October, told TGM staff simply that “his circumstances had changed” and has offered to help someone else take over the business if another financial backer appears. According to a statement, TGM is pursuing both philanthropic and commercial opportunities. But finding a commercial savior seems unlikely without a track record in advertising. TGM had a good base, worthy of sale, but it hasn’t pulled in the readers in the same way as its younger and sexier daily counterpart The Guardian Australia, which Wood is also funding. TGM’s demise was really foreshadowed the moment The Guardian’s digital experts started targeting the Australian market. It’s an increasingly crowded but potentially profitable market for Australia’s influential iPad reading public. And The Guardian, under the editorship of Katharine Viner, proved to be the publication of choice, attracting close to 1.2 million browsers per month in October last year to place it inside Australia’s top 10 news websites. Unlike TGM’s previous incarnation, The Guardian is easy to navigate on all devices, and its digital bells and whistles don’t detract from the stories. TGM attracted criticism upon launch for its unique side-scrolling layout, leading to a sweeping redesign in October 2012. When Wood decided to back The Guardian, he said there was room for both, and that he really supported “independent quality journalism” which he saw as “a foundation of a healthy and civil society.” But with The Guardian he was upfront: He wanted the Australian edition to make money. That’s something The Guardian, with its increasing readership, can potentially offer.

While the closure of TGM isn’t the positive start to the year the Australian media industry had hoped for, it shouldn’t be considered a knock-out punch. Property developer and publisher Morry Schwartz will launch his new newspaper, entitled The Saturday Paper, in March. The Saturday Paper promises to publish longform journalism that

The New Daily, which launched in November 2013, is part-funded by a new player, the industry superfunds network. And the U.K. Daily Mail’s Australian edition will launch this year, with plans to recruit around 50 journalists. Much has been learned from the TGM experiment, and the 21 capable and award-winning staff should soon be re-employed. They’re all old enough and wise enough to know that journalism’s fortunes have long been tied to economic business models (of the private or public kind). As Viner argued last year:

Alex Wake has been a journalist for 25 years. She’s worked in print, radio, television and online in Australia, South Africa, Ireland, and Dubai. She continues to work as a freelance broadcaster, but teaches full time at RMIT University.

|

| The New York Times drops its mobile-app meter from 3 articles a day to 10 a month Posted: 30 Jan 2014 09:58 AM PST

Today, the Times tweaked its meter once again: The company announced that users of its mobile apps would now be allowed 10 free stories a month, according to an email from Times spokesperson Linda Zebian. Once the free-riders hit the meter they’ll be prompted to sign up for a subscription. Browsing section fronts and article summaries inside the app will still be free, as will all videos from the Times. In other words, the mobile apps paywall will look a lot more like the NYTimes.com paywall. Since introducing Paywall 1.0 in 2011, the Times has continually refined the subscription system to try to convert more readers into paying customers. Originally, the Times’ mobile apps set aside a pre-selected set of top stories that were free to readers; the website also used to allow up to 20 freebies a month. This change on the mobile apps comes as the Times is preparing to offer a new collection of news products and digital subscription offerings in the next few months. |

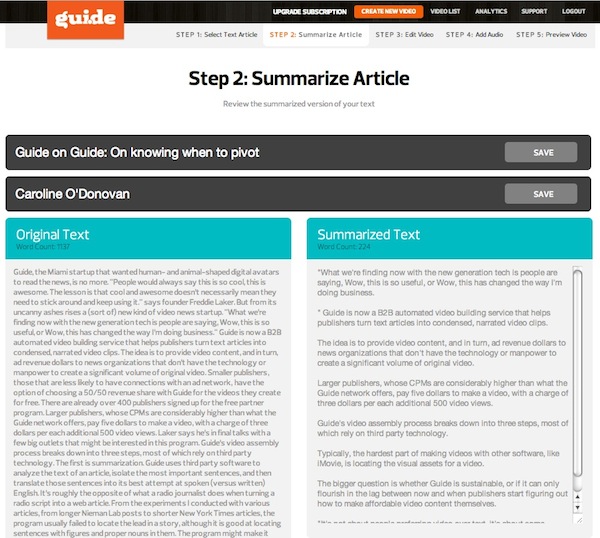

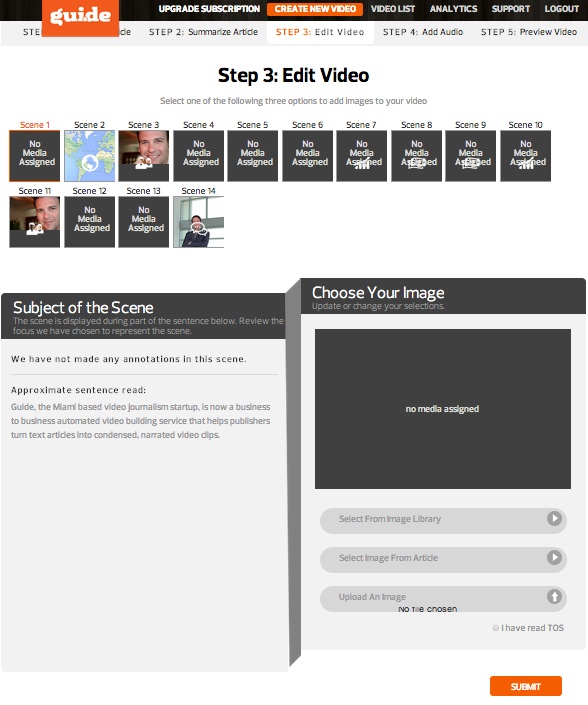

| Guide ditches news anchor avatars in favor of a streamlined, automated video production Posted: 30 Jan 2014 08:39 AM PST If you heard anything about the Miami startup Guide last year, it was likely that it wanted human- and animal-shaped digital avatars to read the news, creating video automatically from stories. That vision is no more. (For video evidence of what that future would have looked like, check out the old Guide website.) “People would always say, This is so cool, This is awesome. The lesson is that cool and awesome doesn’t necessarily mean they need to stick around and keep using it.” says founder Freddie Laker. (Also, some people thought it was super creepy.) But from its uncanny-valley ashes rises a (sort of) new kind of video news startup. “What we’re finding now with the new generation tech is people are saying, Wow, this is so useful, or Wow, this has changed the way I’m doing business.” Guide is now a B2B automated video building service that helps publishers turn text articles into condensed, narrated video clips — minus the creepy avatars. The idea: Publishers can sell video advertising faster than they can actually produce videos. (See Joe Pompeo’s story today to read about The New York Times’ version of that dilemma.) But publishers are good at producing lots of text. If that text can be turned into videos people want to watch automatically (or at least quickly), it could open up new ad revenue. With Guide, smaller publishers — those less likely to have connections with a video ad network or to sell video ads on their own — can choose a 50/50 revenue share for the videos they create for free. Guide says it has over 400 publishers signed up for that free program. Larger publishers, whose CPMs are considerably higher than what the Guide network can offer, pay five dollars to make a video, with a charge of $3 per each additional 500 video views. Laker says he’s in final talks with a few big outlets that might be interested in this program. How it worksGuide’s video assembly process breaks down into a series of steps, most of which rely on other companies’ technology. After choosing an article, the first big step is summarization. Guide uses third-party software to analyze the text of an article, isolate what it thinks are the most important sentences, and then translate those sentences into its best attempt at spoken (versus written) English. It’s sort of a mishmash of Summly and the opposite of what a radio journalist does turning a radio script into a web article.

I tried using Guide with a number of different stories, from longer Nieman Lab posts to shorter New York Times articles, and the results were mixed. The program regularly failed to identify which sentence in the text would make the best logical opening line for a video; it was better at pulling out sentences with numbers and proper nouns in them. (Guide really likes numbers.) The program might make it easier for an editor unfamiliar with a story to summarize it and break it down into slides, but the actual author of a story could probably do the job faster on their own. After the summarizing, it’s on to the visual phase. Guide measures the approximate length of the script when read aloud and auto-populates the appropriate number of slides. Using natural language processing based on Stanford’s CoreNLP project, Guide attempts to recognize newsy elements in a story— numbers, dates, locations, people’s names, companies — and inserts either a simple animation — a turning calendar pages, scrolling numbers — or an appropriate image.

“Whether it be additional images or extrapolating block quotes or numbers or currencies or locations or maps, pulling extra data for things like DBpedia to enhance the videos, I think we’re adding a lot of substance,” Laker says. Typically, Laker argues, the hardest part of making videos with other software is locating the visual assets for a video. “The editing is the easy part,” says Laker. “That’s what’s time consuming, finding all the stuff.” Though Laker says the program usually fills between 60 and 80 percent of the slides, in my test using an early version of this article, it managed to fill less than 30 percent. In experimenting with other stories, my results were about the same. And Laker is right — finding visual elements on my own was difficult and time-consuming, even with minimal effort. In addition, the animations can be distracting or just beside the point: For example, in a sentence that delineates two sides of a conflict, a rolling ticker that counts from 1 to 2 is simply not illuminating. (For now, users are stuck with those animations, but a Guide representative said they are working on it.) Once you’ve got a script and corresponding images, the final step is to find someone — or something — to narrate the video. The reporter or editor can make an original recording, or, for the top tier customer, at $20 a hit, a professional voice actor will record a reading of the article. But the truly innovative option, which is also facilitated by third-party software, is text-to-voice. Editors can choose from two American English female voices and one male voice, or a British female voice. And with that, the video is ready to publish, and looks a little something like this. (We used a human narrator; Guide gives you two free credits to do so.) Despite the bumps in the road, Laker’s ability to pivot and iterate should not be overlooked. “I started realizing, I raised all this money. I’ve got to do something, and I’ve got to do it quick,” he says of his decision in December to take whatever was left of his $1.5 million in seed funding and convert Guide from a consumer service to product-based company. (Some of that money came from the Knight Foundation, which has also provided funding to Nieman Lab.) At that time, he also realized he needed more feedback from publishers than he’d been getting. “We’ve spoken to — without exaggerating — hundreds of editors and publishers across America, and actually a couple in Europe,” he says. “I would say on average, I speak to three to five publishers a week in a strictly interview format. Very strict no-selling rules, just learning.” Laker has taken this lesson about feedback to heart. Guide is committed to updating every few weeks and, although the new site has some bugs, the team seems to be approaching them like so many Whack-a-Mole moles. For example, Laker says it will soon be possible to embed video files in a Guide video, which could improve production values considerably. If one buys the idea that we’re headed toward increasingly automated video production, the bigger question is whether Guide is sustainable — or whether it can only flourish in the lag between now and when publishers start figuring out how to make affordable video content themselves. (There’s also the even bigger question: How much is the boom in video advertising CPMs supported by the fact that quality video production is hard? If suddenly we have 1,000× more quality video thanks to better automation, wouldn’t that send ad rates tumbling, just as happened with banner ads?) Laker says the ever increasing demand for video content makes him confident about the space he’s playing in. “It’s not about people preferring video over text — it’s about some people preferring video over text,” he says. “Even if only 10 percent of people would rather watch a video summary, then this is very viable.” (Note that, in the Guide video above, the narrator has trouble catching the emphasis on the some in Laker’s quote; a robot would have fared even worse.) But he’s not the only one that thinks so. Wibbitz is just one of the several companies that’s been working on perfecting the text-to-video transformation for longer than Guide. (The Wibbitz team, based in Tel Aviv, said they didn’t want to comment for this story.) Also experimenting with cheap, viral, mobile video is NowThis News, a company which recently received a major investment from NBC and which is betting on humans over algorithms. And, of course, there’s the ever bizarre but not-to-be-laughed-off Next Media Animation in Taiwan, and its corresponding partnership with Reuters. With so many ad dollars in video, it’s only going to get harder to stand out in this field. Laker is smart to want to get into the readymade video business, but the question is whether the minimally-compelling-at-best content Guide currently produces will have a chance to make a mark in it. |

| The newsonomics of the for-profit move in local online news Posted: 30 Jan 2014 07:00 AM PST Josh Fenton is an ad guy running a local news startup. Therein lies our tale. GoLocal24 is a different kind of online startup. It’s for-profit, unlike so many of the city startups we’ve seen. It’s fueled solely by advertising revenue, while many other startups get no more than 20 percent of their income from ads and sponsorships. It claims a 20 percent profit margin, when a break-even balancing of foundation, grant, membership, events, and ad income vs. expenses serves as a wider model among its nonprofit peers.

The Portland site — set to launch this spring — will double the number of GoLocal staffers. Portland will have six editorial staffers and four business-side ones, equaling the 10 total staffers putting out the Providence and Worcester sites. GoLocal could have picked Portland, Maine — much closer to home — but wants to announce itself as a national company and a national model, so it’s the Portland on the other side of the country that will do that. If Portland succeeds, Fenton and his investors plan more GoLocals — and have already bought dozens of URLs to enable that. It’s a noteworthy move, coming on the heels of the near-final implosion of Patch this week. Like a vast stadium slated for demolition, the slo-mo demise of Patch — just recently the No. 1 hirer of U.S. journalists — has been painful to watch. Through 2013, AOL CEO Tim Armstrong dribbled out information on key questions: Which sites will stay, and which will go? To whom, and how? Or would they just close in the middle of the night some time this year? AOL had been remarkably unclear with its publics, its staff, and its readers about those questions. Then, the expected news yesterday: New majority Patch owner Hale Global would dispatch more than 75 percent of the remaining journalists. Now expect the new ownership to harvest as much of the traffic and brand value of the sites at as low a cost as possible, using local aggregation and low-cost, programmatic sales. What once the biggest experiment in local journalism will live on largely in ghost form. In midsummer, as Patch’s direction was becoming clearer, we saw the usual spate of posts on the impossibility of “hyperlocal.” We can conclude that it’s the hype part of hyperlocal that’s been overplayed. Local is local — we know it when we see it, and we know when it’s well-done and when it isn’t. GoLocal’s decidedly contrarian turn on local is worth understanding in the Patch context. Providence is a big, old city. Its metro area stretches into Massachusetts and touches eight counties. What happens in the Elmhurst neighborhood is different than what happens in the Elmwood neighborhood — yet the residents of both care about both their neighborhoods and the wider metro area, its crimes, schools, and only-in-Providence brand of politics. GoLocal emphasizes the city-wide issues — knowing that’s what (duh) brings in the engagement of audiences. It’s really just an application of old newspaper principles to digital local: It’s both city and neighborhood news that stokes readership. It’s worth stating that principle, given that Patch’s belief that hyperlocal was enough to build a business might have been its most fatal flaw. Merrill Brown, a veteran and smart observer of local back to his early days plying online at MSNBC.com, is now a board member and minor investor in GoLocal. Over the holidays, he wrote a piece for Forbes comparing Patch and GoLocal. His conclusion and his GoLocal pitch:

It’s worth noting the kinds of communities that GoLocal has picked to operate in. While Portland is in economic recovery, with jobless rates falling below 7 percent; Providence’s is more than 9 percent, one of the highest in the country. While Fenton says that GoLocal looks at a diverse set of data points in picking its locations, another fact stands out: Each of its first three locations is home to struggling dailies. The Providence Journal has been in a long tailspin of reader, ad, and staff loss and has been recently put on the market by owner A.H. Belo. The Worcester Telegram & Gazette, sold by The New York Times Co. to John Henry in the Boston Globe deal, has survived recent years in better shape than the ProJo, but it too is now up for sale. (Dean Starkman, a Columbia Journalism Review editor, former Providence Journal reporter, and now regular contributor to GoLocal, details the Telegram story here and the ProJo’s here.) In Portland, The Oregonian — by far the largest daily in the state — is an Advance paper, which means it’s retrenching on print, its community footprint receding along with it. It’s not quite a vacuum, but it’s a vulnerability. Low-cost, high-energy startups, like GoLocal, can exploit the weakness. What is GoLocal’s playbook?

What about GoLocal’s journalism? It’s a startup in every sense of the word. Knowledgable observers credit it with some agenda-setting journalism and lots of engaging coverage — and fault it for incompletely sourced stories that may over-promise. Check out its home page. It’s in constant motion. As a true startup founder, ad leader, and effective editor-in-chief, Josh Fenton runs a work-in-progress. That’s fair to expect from a two-plus-year-old startup. As the company expands, one big test is to come: How much more experienced and stable editorial leadership does it hire on? In Portland, it will face a bigger challenge. Fenton has regularly visited Portland, doing his homework, aware that it’s a far different audience (Portlandia is only partly satiric) and market than his northeastern. It’s also more journalistically diverse, with one of the country’s best urban weeklies in Willamette Week, in addition to The Oregonian, other weeklies, active TV stations, and an innovative public media network in Oregon Public Broadcasting. To try to meet that challenge, GoLocal’s Portland operation will have the same number of full-time journalists (six) as do Providence and Worcester combined. It’s important to consider where we’re at in local media models. They’re struggling. Just this week, the Knight Foundation put millions more into helping build the sustainability of local online news. That grant follows up a comprehensive and to-the-point J-Lab report that showed, unsurprisingly, that online startups need to “create space for business capacity.” As well meaning as it is, it sounds like a Republican punchline to a joke about a Democrat’s anti-business leanings. We can ask about for-profit vs. nonprofit local news models, but our question isn’t whether one is better than the other. I’m agnostic on that question: More good journalism, however funded, is better than less. That’s one reason the GoLocal model is an important one. Nobody had to tell Josh Fenton about the need to build business capacity; he’s an ad guy who knew he was running a business before day one. We see what looks like two kinds of local ships headed in opposite directions: the (mostly) nonprofits largely run by dedicated, community-minded editors who are trying to figure out the world of business because they have to — and the for-profit model that operates like any other small business. Undoubtedly, the nonprofits are better staffed editorially — more and more experienced journalists — than GoLocal, which carefully spends each dime to build its business along with its news-gathering capacity. That’s where the Fentons fit, and why we need more of them in the mix. Editors-turned-publishers can learn the nuances of digital business — but advertising natives like Fenton bring a far different experience and perspective — in addition to all those relationships — to local media creation. Fenton is a believer in profit-seeking businesses. Though he doesn’t disparage the nonprofit local model, he believes that going for-profit provides an edge of sink-or-swim discipline to the endeavor. I’ve heard similar sentiments from other news startups choosing for-profit status, as they make the case that for-profits selling advertising are regarded very differently by businesspeople that non-profits. Both points — the discipline edge and commercial acceptability — are debatable, but perhaps vital as we look at the reconstruction of local news in our time. In an ideal world, we’d see a better meeting ground. We need serious business natives juiced about the building of local digital news companies, working in tandem with tenacious editors and reporters out to serve communities. Getting the models right — sooner rather than later — is essential. It’s no accident that GoLocal has gone into the under-served cities it has. The critical question about local journalism is replacement: how to replace the vast staffs, beats, and inches of reporting that have simply disappeared since 2007. Replacement will never be (and shouldn’t) one-to-one, but volume — and the quality of that volume — matters across the country. Photo by Christopher Michel used under a Creative Commons license. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Nieman Journalism Lab To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

This article was originally published at

This article was originally published at  Last summer, The New York Times brought its mobile apps more in line with the rest of the company’s digital offerings by creating a meter that

Last summer, The New York Times brought its mobile apps more in line with the rest of the company’s digital offerings by creating a meter that

Sure of its model, it’s now building out a small chain. Started in

Sure of its model, it’s now building out a small chain. Started in

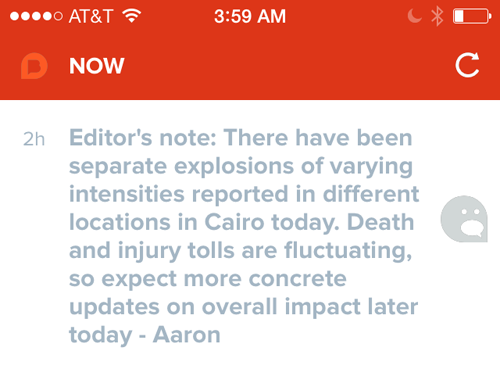

On the plus side, the Inside formula — 300 characters, 40 words, 10 facts per update, designed to meet founder

On the plus side, the Inside formula — 300 characters, 40 words, 10 facts per update, designed to meet founder  But does it solve any problems for a user? Calacanis wants it to reduce the noise of getting the news. If a user is willing to rely on Inside to get just enough news on a story — not all breaking reports or complete aggregation — it will probably be sufficient most of the time. I’ve been trying

But does it solve any problems for a user? Calacanis wants it to reduce the noise of getting the news. If a user is willing to rely on Inside to get just enough news on a story — not all breaking reports or complete aggregation — it will probably be sufficient most of the time. I’ve been trying  Twitter has the tweet as their atomic unit of content. We have something called an update. This is an editorial format I’ve worked on for the past over a year, actually, at

Twitter has the tweet as their atomic unit of content. We have something called an update. This is an editorial format I’ve worked on for the past over a year, actually, at  Knight just announces it’s launching a new $1 million fund to support innovation in nonprofit and public media organizations. The new INNovation Fund is a collaboration between Knight and the

Knight just announces it’s launching a new $1 million fund to support innovation in nonprofit and public media organizations. The new INNovation Fund is a collaboration between Knight and the